| Every cradle is a grave |

|

|

|

Human cognition is a mixture of the rational and the magical. Religious thinking is even more important than rational thinking for people deciding how to behave, and this is the case even for people who do not consider themselves religious. The rationality of analytic philosophy is a powerful tool for understanding the world, but the world of human cognition cannot be comprehended without attention to the religious, the magical, and the sacred. The first part of this book deals with the irrational side of human cognition, exploring our need for meaning and our attribution of meaning and sacredness. The second and third parts of this book engage with rationality.

Here is an overview of the central thread connecting the parts:

- People have innate needs for meaning—needs for some ultimate, foundational value that justifies all other values; for purpose in life; for a sense of efficacy and control; and for a sense of self-worth.

- The meanings that people find in the world are generally illusory—for instance, promised future states of fulfillment that never occur.

- Since meaning is both necessary AND illusory, people must protect their valuable sources of meaning from disparagement with the armor of sacredness.

- One of the most sacred and meaning-giving beliefs is the idea that life is a desirable, precious thing to have and to give to others. This sacredness prevents us from thinking clearly about suicide and birth. It is the most poignant example of Jonathan Haidt’s “ring of motivated ignorance” that surrounds the sacred.

- However, for the most intrepid explorers, challenging the essential sacredness of life—one of the most powerful shared sources of meaning in our sacredness-deprived culture—may mean crossing a frontier into new and unexpected insights and new ways of conceiving of humanity and compassion, especially with respect to suicide and procreation.

***

This book engages with analytic philosophy, particularly in its approach to antinatalism and suicide rights. But it also engages with the responses of non-philosophers, whose approaches are probably more representative of ordinary human thought than are more sophisticated treatments found in the literature of analytic philosophy.

Chapter 1 engages with Bryan Caplan’s self-described “cursory rejection” of antinatalism, grounded in the claim that if life is so bad you can always commit suicide (in my experience, an overwhelmingly common first response to antinatalism). This chapter introduces antinatalism and explains the connection between antinatalism and suicide.

Chapter 2 is about meaning—what kinds of meaning we require as humans, and how we find that meaning in the world. The connection between meaning and suffering is explored.

Chapter 3 introduces Jonathan Haidt’s “moral foundations” approach, illustrating how sacredness and purity, care for others, fairness concerns, and loyalty influence our beliefs.

Chapter 4 elaborates on Robert Nozick’s famous “Experience Machine” thought experiment, motivating a radical perspective in which mental states are the only objects of moral consideration. Ethical issues are explored from this perspective.

Part II focuses on suicide. Chapter 5 analyzes suicide and childbearing from a moral foundations perspective. Chapter 6 examines the causes of suicide, including an exploration of the evolutionary biology of suicide. Chapter 7 engages with the work of Jennifer Michael Hecht, whose popular philosophy book argues that we have a duty to not kill ourselves because doing so gives moral license to others to also commit suicide. This chapter examines the phenomenon of suicide contagion, presenting evidence that it is not moral license but rather the transmission of much-desired information that is responsible for the rare phenomenon of suicide “contagion.” The phenomenon of suicide contagion is also cited in favor of censoring media reports of suicide as well as the depiction of suicide in art and discussion; Chapter 8 examines the censorship of suicide.

Part III is about procreation. Chapter 9 provides a roadmap to the ethical arguments involved, both preferentist (believing that people know what is good for them) and non-preferentist (believing that people do not necessarily know what is good for them). Chapters 10 and 11 explore preferentist arguments, demonstrating that people frequently act as if life is a burden rather than a precious gift. Chapter 12 presents non-preferentist arguments against procreation. Chapter 13 connects the human predicament to that of the rest of the creatures in the world and in our evolutionary history.

Finally, I include as an appendix a personal essay about the lack of narrative meaning.

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Breaking the Ring of Motivated Ignorance

PART I: A Worldview of Worldviews

Chapter One: Free Disposal and the Burden of Life … 1

The Suicide Prohibition

The Cost of Disposal

The Land of Free Disposal

The Burden of Life

Chapter Two: The Empirical Nature of the Meaning of Life … 6

The Needs for Meaning

Value

Social belonging

Purpose

Efficacy

Self-worth or status

How Meaning Operates: Methods and Illusions

Meaning infection

False permanence

Suffering measures meaning

Illusion of control

The Story

Non-fungibility of meaning

Chapter Three: The Modern Sacredness and Moral Foundations … 20

Morphology of the Sacred

A Window into Sacredness: The Violation

Sacredness Negotiations

Moral Foundations

Sacrednesses Old and New

A Necessary Danger

Chapter Four: Experience Machines and Their Ratification … 27

The True Gifts of the Good People: How Experience Machines Help Us Escape Uncertainty

Friendly Neighborhood Experience Machines: Where Do They Come From?

Aesthetics and Religions: A Minor Distinction

A Sneaky Dualism

The Co-Evolution of Humans and Their Experience Machines

The Protection of an Aesthetic

Ourselves as Experience Machines

PART II: The Ethics of Suicide and the Suicide Prohibition

Chapter Five: Moral Foundations Analysis of Suicide and Childbearing … 35

Suicide and Moral Foundations

Childbearing and Moral Foundations

Chapter Six:What Really Causes Suicide … 38

Failed Social Belonging

Burdensomeness

Competence

What Doesn’t Cause Suicide

Evolutionary Considerations

Attempted Suicide as an Adaptive Behavior: Suicide Gambles

Chapter Seven: On Contagion … 45

Behavioral Contagion

Ethical Perspectives on Suicide Contagion

The Science of Suicide Contagion

Moral Contagion or Informational Contagion?

Mass Clusters and Point Clusters

The Death of Marilyn Monroe

Why Women?

Other Factors in Contagion: Negative Definition of Suicide

Chapter Eight: The Censorship of Suicide … 53

Censorship of Suicide versus Censorship of Violence

Contagion and Moral Responsibility

Moral Responsibility and Willingness to Censor

PART III: The Ethics of Procreation

Chapter Nine: Procreative Responsibility: A Road Map … 57

Liberty

Harm and Measurement: Preferentist and Non-Preferentist Approaches

Preferentist Approaches and Evidence

Free Disposal and the Imaginary Survey

Revealed Preference in Non-Suicidal Behavior

Non-Preferentist Approaches

Naive Weighing

Benatar’s Asymmetry

Shiffrin’s Asymmetries

Uncertainty

Chapter Ten: The Mathematics of Misery … 68

Truncated Utility Functions and the Value of Life

Negative Utility and the Death Wish Economy

Policy Implications

What Real Human Utility Functions Are Functions Of

Poor Baby or Rich Baby: Which is Worse?

The Economics of Palliation and Bullshit

Chapter Eleven: The Burden of Life … 75

Work and Leisure

Poverty and Pain

The Demand for Pain Relief

Is Loss Aversion Irrational?

A Place for Quantitative Methods

Chapter Twelve: Hurting People and Doing Good … 81

Chapter Thirteen: The World of Nature of Which We Are a Part … 82

1. On The Ways In Which Nature Makes Andrea Yates Look Like June Cleaver

2. The Incoherence of Species-Relative Morality

3. Respect for Species?

4. Use Nature As We Please?

5. Is Being Human-Like Better?

Appendix: Living in the Epilogue: Social Policy as Palliative Care … 88

The Story as a Cognitive Bias

Living in the Epilogue

There Are No Stories In Heaven

The Cheery and the Damned

Palliative Care: A Double Standard for People in the Epilogue

Toward Social Policy as Palliative Care

This is a book about ethics. People don’t often change their minds about ethics. When they do, it is generally for social reasons, not because they are exposed to reasoned argument. Reasoned arguments more often allow people to cement their existing opinions. Ethical beliefs are, in any case, extremely limited in their ability to influence actions.

I will advocate several ethical positions that are counterintuitive, and that some people would describe as evil. These ethical positions include the view that life—not just human life, but all life capable of having experiences—is very bad. It is very immoral, I will argue, to have babies or to otherwise create aware beings. I will also argue that suicide is not wrong or a product of mental illness, but an ethically privileged, rational response to the badness of life.

You might imagine these to be positions held by a comic book villain bent on destroying all life in the universe for its own good. That’s fine with me. In fact, it’s a good place to start. Because in presenting what I hope is a reasoned and factually supported ethical argument advocating such extreme ideas, I do not expect to persuade. It is more likely that I will be mentally categorized by the reader as such a cartoon villain (assuming the reader is not one of those few to whom these cartoon villain ideas seem obviously right). And to the extent that the reader holds contrary, prolife, anti-suicide beliefs, I understand that exposure to my unorthodox views may only reinforce those beliefs.

Believe it or not, that seems pretty rational to me. To respond to crazy-sounding out-group beliefs with increased faith in the in-group beliefs validated by known and trusted authority—is a smart strategy. From the trenches of interpersonal communication, I don’t think “ad hominem” is even much of a fallacy. On the contrary, consciousness—and all knowledge—is social in nature; and most of our knowledge comes not from direct experience or through reasoning, but from trusted sources. Though some of our beliefs about the physical world come from direct experience, we mostly rely on the trusted testimony of teachers, scientists, and friends to understand such things that we have no direct experience of, or of which our direct experience is understood to be limited or mistaken. The Earth appears to be flat, and the sun, which looks like it is smaller than the Earth, appears to be moving around the earth. We know better only because we are reliably advised that our initial sensory impressions are incorrect. In a similar way, we get some of our ethical beliefs from direct intuitive perception, but we also rely on the ethical beliefs of those around us to shape our own beliefs and actions. We are much more likely to be vegetarians if our friends are vegetarians. We are much less likely to support gun control if our friends are gun enthusiasts.

Many readers will find it natural to think of the self as the ultimate arbiter of ethical questions, but this is based on a modern and distinctly Western conception of the self. And even self-heavy moderns will sometimes admit to confusion as to what is the right thing to do in a morally unclear situation. Who, then, is to be consulted and trusted on issues of moral relevance? And what should be the result if one disagrees with a trusted friend on a moral matter?

There are some people—crazy people, evil people, people who have taken large amounts of methamphetamines for days on end—whose disagreements with our opinions on ethical matters would not cause us to have any doubts as to the correctness of our own opinions (possibly the opposite, as noted above). But any socially well-adjusted human being is likely from time to time to encounter a person whose contrary opinions are less easily dismissed. When we engage with such a person—who is so trusted, whose mental apparatus has been so verified to work well, and whose motives are so clearly earnest—we may come away less certain about the correctness of our own views. I like the term “epistemic peer” for a person so trusted, brain-wise and team-wise, that his opinion will be taken very seriously when it disagrees with our own.

I am more interested in establishing myself as an epistemic peer of the reader than in autistically presenting a logical argument for the correctness of my views. When you find yourself coming to an unusual conclusion and you can’t find a flaw in your own reasoning, the epistemically proper path, I think, is to show your brain and show your work. You display the way your mind (your laboratory apparatus) approaches the problem, and you present your argument (your laboratory protocol) in a clear way so that others may examine it.

As I would rather participate in social reasoning than table-pound in my corner, I will not only present the extreme forms of my arguments (many of which I think are correct); I will also attempt to present the continuum for each position, many points along which are uncontroversially reasonable. More important, I will show that such continua exist. I consider many people reasonable who do not go full cartoon villain and agree with me that all life is unfortunate and nobody should ever have babies. What makes such people seem reasonable to me is that they recognize the possibility that a given life could go very badly, and that the joys of life might not outweigh the suffering. At the very least, they recognize that the interests of an aware being are very hard to predict before that being is created.

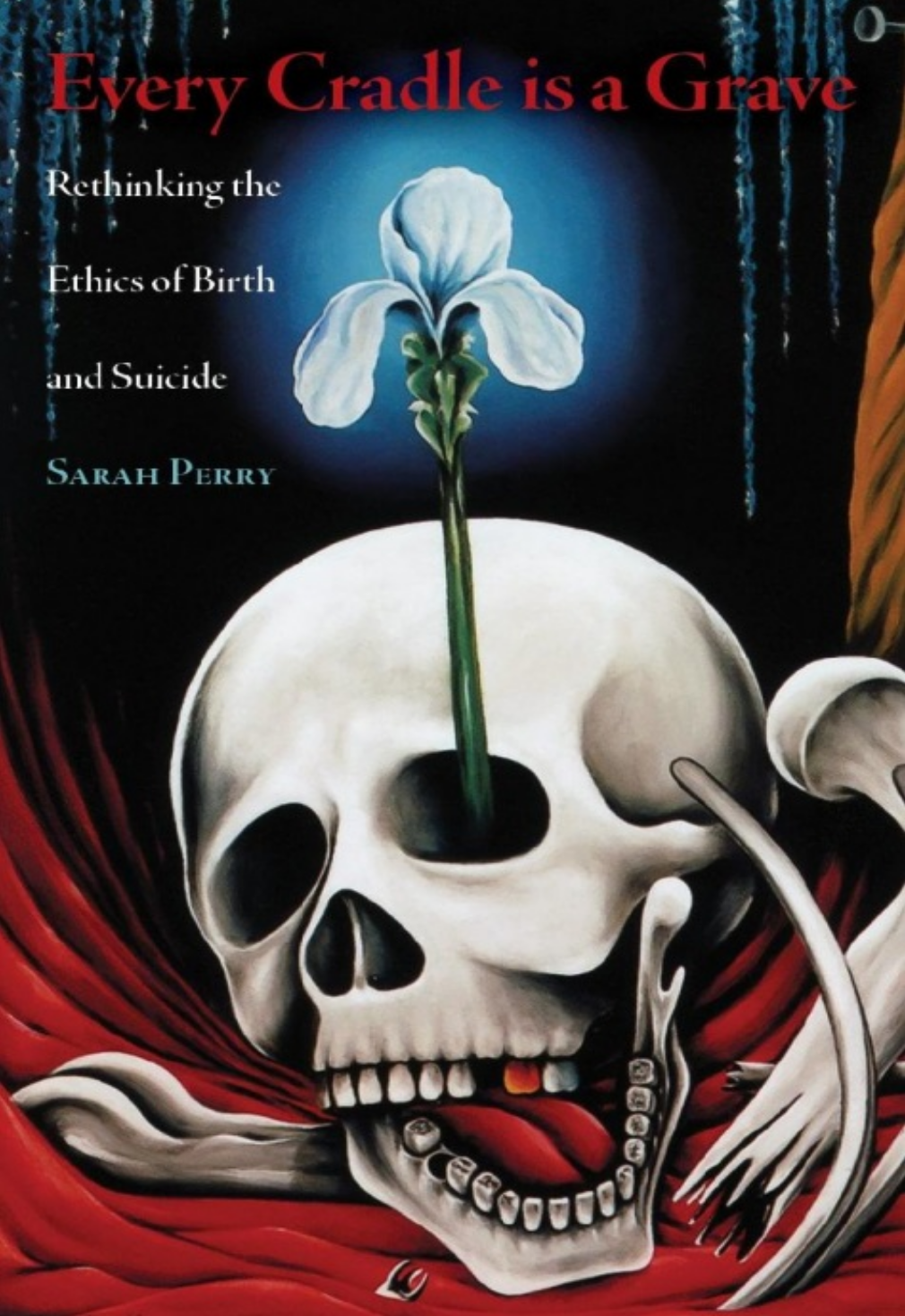

What I would like readers of this book to come away with is not the urge to bomb IVF clinics or dismantle suicide barriers on bridges. I would prefer that readers simply and sincerely consider the question of whether existence is a blessing or a burden, and I hope to encourage the understanding that for many people, it is a useless burden. I would like the reader to think of parenthood as a moral decision affecting a new human being, rather than an event that merely happens to oneself. I would like the reader to consider that it may be both more important and more possible to prevent harm than to do active good in the world. I would like readers to consider the mental states of aware beings as being a very important, if not terminal, locus of ethical value in the universe. Finally, I would like readers to dig further into the nature of their own values, especially the primitive values of survival and longevity. If these points are communicated, I will have done my duty to the late Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who suffered much in his life for the good of others and who, before his death, kindly gave me permission to use one of his paintings on the cover of my book.

The prevailing views on birth and suicide, I will argue, are very misguided. But they are misguided in characteristically human and evolutionarily adaptive ways. In order to reject them, we must approach what David Eubanks has called the Frontier of Occam—the highest intelligence achievable by a civilization before it figures out better ways to achieve its ends than by continuing to pursue the goals of its alien creator, evolution.

I suspect that I have made more converts to the cause of questioning life’s value simply by being an adorable housewife who makes a killer chanterelle risotto than by any particular argument I’ve constructed. Since I can’t make you risotto, I have tried to present my arguments in a calm and reasoned manner, with abiding respect for the humanity that we all share. Perhaps I will come across as the sort of cartoon villain you should accept as an epistemic peer. But whether or not you allow me to influence you with my dangerous ideas, I hope you will believe me when I tell you that I am very much on your side. You are, after all, an aware being having experiences. This is true whether or not you have had or will have children, and this is true whether you want to live or want to die.

Thank you for reading my book.

I would like to thank Chip Smith of Nine-Banded Books for bringing this book into existence over the past four years, for suggesting that I write it, and for encouragement, technical assistance, and friendship along the way. Thanks to everyone who has read early versions of this book and provided helpful criticism and editing assistance—Thomas Ligotti, Ann Sterzinger, Jim Crawford, Anita Dalton, Samuel Crowell and Sam Frank, among others.

Thanks to Rob Sica for his philosophy scholarship and librarian assistance, and to readers and commenters of my blog. Thanks to my family, Nona Perry, Dan Perry, Nona Baker, Michelle Perry, Gleta and George Perry, and Kris and George Perry; and to my husband, Andrew Breese, for supporting my work and exploring ideas with me; and to my friends Sarah Lennon, Megan Robb, Phil Ogston, and C. Thi Nguyen. I would like to thank the late Dr. Jack Kevorkian for permission to use his evocative painting as cover art. Finally, I would like to thank Unaffiliated Smartypants Twitter for engaging with crazy ideas with me over the past few years (which acknowledgment is not meant to suggest that such a thing as Unaffiliated Smartypants Twitter exists).

|

Credit: Joshua Zader

Sarah Perry is a housewife in San Antonio, Texas. This is her first book.

Copyright

Every Cradle Is A Grave

Rethinking the Ethics of Birth and Suicide

Sarah Perry

Copyright © 2014

Published by Nine-Banded Books, PO Box 1862, Charleston, WV 25327, USA

NineBandedBooks.com

ISBN-10: 0989697290

ISBN-13: 978-0989697293

Cover painting: Very Still Life by Dr. Jack Kevorkian (1928–2011)

Cover design by Kevin I. Slaughter