|

Every cradle is a grave |

|

|

|

|

Human cognition is a mixture of the rational and the magical. Religious thinking is even more important than rational thinking for people deciding how to behave, and this is the case even for people who do not consider themselves religious. The rationality of analytic philosophy is a powerful tool for understanding the world, but the world of human cognition cannot be comprehended without attention to the religious, the magical, and the sacred. The first part of this book deals with the irrational side of human cognition, exploring our need for meaning and our attribution of meaning and sacredness. The second and third parts of this book engage with rationality.

Here is an overview of the central thread connecting the parts:

- People have innate needs for meaning—needs for some ultimate, foundational value that justifies all other values; for purpose in life; for a sense of efficacy and control; and for a sense of self-worth.

- The meanings that people find in the world are generally illusory—for instance, promised future states of fulfillment that never occur.

- Since meaning is both necessary AND illusory, people must protect their valuable sources of meaning from disparagement with the armor of sacredness.

- One of the most sacred and meaning-giving beliefs is the idea that life is a desirable, precious thing to have and to give to others. This sacredness prevents us from thinking clearly about suicide and birth. It is the most poignant example of Jonathan Haidt’s “ring of motivated ignorance” that surrounds the sacred.

- However, for the most intrepid explorers, challenging the essential sacredness of life—one of the most powerful shared sources of meaning in our sacredness-deprived culture—may mean crossing a frontier into new and unexpected insights and new ways of conceiving of humanity and compassion, especially with respect to suicide and procreation.

***

This book engages with analytic philosophy, particularly in its approach to antinatalism and suicide rights. But it also engages with the responses of non-philosophers, whose approaches are probably more representative of ordinary human thought than are more sophisticated treatments found in the literature of analytic philosophy.

Chapter 1 engages with Bryan Caplan’s self-described “cursory rejection” of antinatalism, grounded in the claim that if life is so bad you can always commit suicide (in my experience, an overwhelmingly common first response to antinatalism). This chapter introduces antinatalism and explains the connection between antinatalism and suicide.

Chapter 2 is about meaning—what kinds of meaning we require as humans, and how we find that meaning in the world. The connection between meaning and suffering is explored.

Chapter 3 introduces Jonathan Haidt’s “moral foundations” approach, illustrating how sacredness and purity, care for others, fairness concerns, and loyalty influence our beliefs.

Chapter 4 elaborates on Robert Nozick’s famous “Experience Machine” thought experiment, motivating a radical perspective in which mental states are the only objects of moral consideration. Ethical issues are explored from this perspective.

Part II focuses on suicide. Chapter 5 analyzes suicide and childbearing from a moral foundations perspective. Chapter 6 examines the causes of suicide, including an exploration of the evolutionary biology of suicide. Chapter 7 engages with the work of Jennifer Michael Hecht, whose popular philosophy book argues that we have a duty to not kill ourselves because doing so gives moral license to others to also commit suicide. This chapter examines the phenomenon of suicide contagion, presenting evidence that it is not moral license but rather the transmission of much-desired information that is responsible for the rare phenomenon of suicide “contagion.” The phenomenon of suicide contagion is also cited in favor of censoring media reports of suicide as well as the depiction of suicide in art and discussion; Chapter 8 examines the censorship of suicide.

Part III is about procreation. Chapter 9 provides a roadmap to the ethical arguments involved, both preferentist (believing that people know what is good for them) and non-preferentist (believing that people do not necessarily know what is good for them). Chapters 10 and 11 explore preferentist arguments, demonstrating that people frequently act as if life is a burden rather than a precious gift. Chapter 12 presents non-preferentist arguments against procreation. Chapter 13 connects the human predicament to that of the rest of the creatures in the world and in our evolutionary history.

Finally, I include as an appendix a personal essay about the lack of narrative meaning.

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Breaking the Ring of Motivated Ignorance

PART I: A Worldview of Worldviews

Chapter One: Free Disposal and the Burden of Life … 1

The Suicide Prohibition

The Cost of Disposal

The Land of Free Disposal

The Burden of Life

Chapter Two: The Empirical Nature of the Meaning of Life … 6

The Needs for Meaning

Value

Social belonging

Purpose

Efficacy

Self-worth or status

How Meaning Operates: Methods and Illusions

Meaning infection

False permanence

Suffering measures meaning

Illusion of control

The Story

Non-fungibility of meaning

Chapter Three: The Modern Sacredness and Moral Foundations … 20

Morphology of the Sacred

A Window into Sacredness: The Violation

Sacredness Negotiations

Moral Foundations

Sacrednesses Old and New

A Necessary Danger

Chapter Four: Experience Machines and Their Ratification … 27

The True Gifts of the Good People: How Experience Machines Help Us Escape Uncertainty

Friendly Neighborhood Experience Machines: Where Do They Come From?

Aesthetics and Religions: A Minor Distinction

A Sneaky Dualism

The Co-Evolution of Humans and Their Experience Machines

The Protection of an Aesthetic

Ourselves as Experience Machines

PART II: The Ethics of Suicide and the Suicide Prohibition

Chapter Five: Moral Foundations Analysis of Suicide and Childbearing … 35

Suicide and Moral Foundations

Childbearing and Moral Foundations

Chapter Six:What Really Causes Suicide … 38

Failed Social Belonging

Burdensomeness

Competence

What Doesn’t Cause Suicide

Evolutionary Considerations

Attempted Suicide as an Adaptive Behavior: Suicide Gambles

Chapter Seven: On Contagion … 45

Behavioral Contagion

Ethical Perspectives on Suicide Contagion

The Science of Suicide Contagion

Moral Contagion or Informational Contagion?

Mass Clusters and Point Clusters

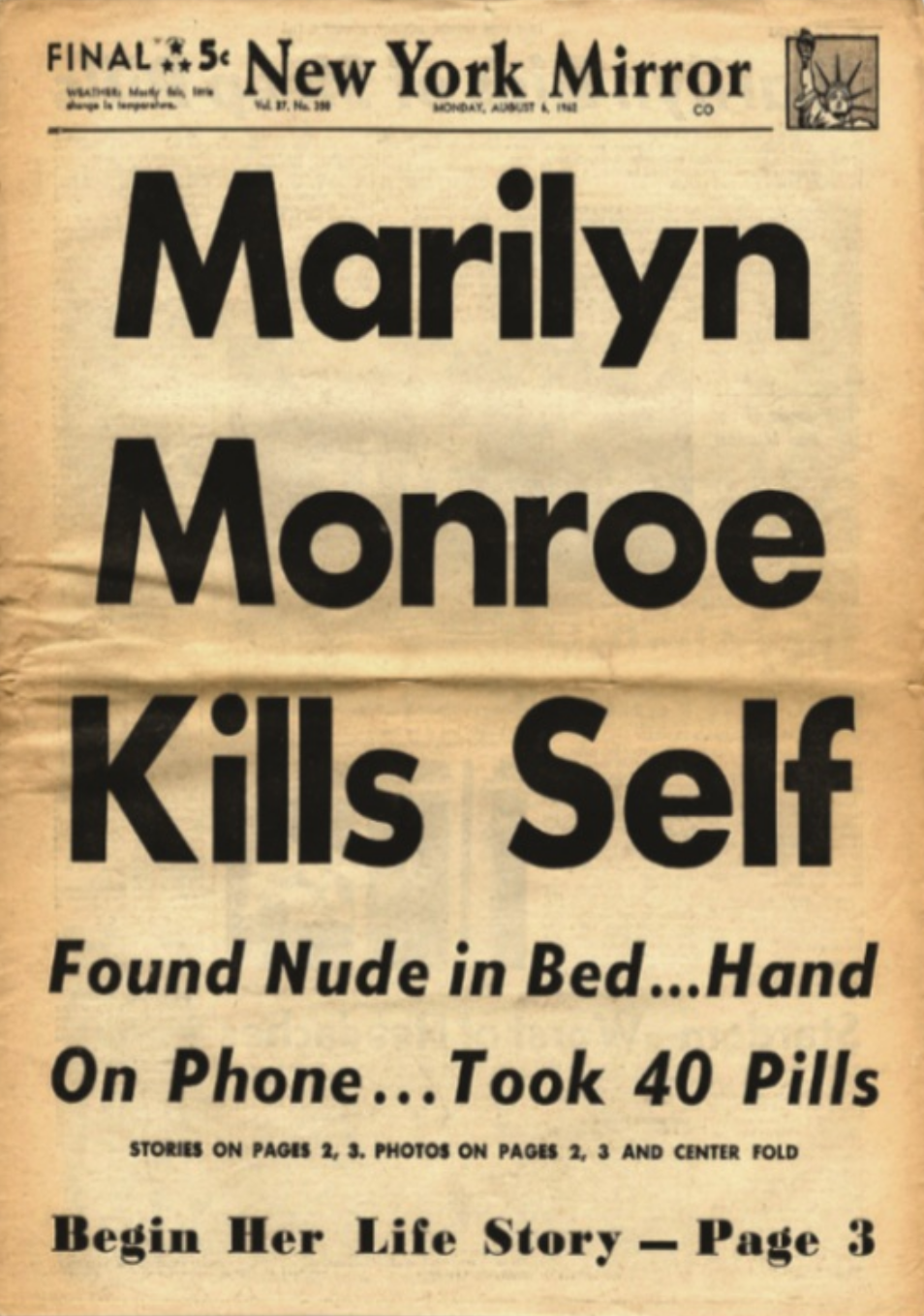

The Death of Marilyn Monroe

Why Women?

Other Factors in Contagion: Negative Definition of Suicide

Chapter Eight: The Censorship of Suicide … 53

Censorship of Suicide versus Censorship of Violence

Contagion and Moral Responsibility

Moral Responsibility and Willingness to Censor

PART III: The Ethics of Procreation

Chapter Nine: Procreative Responsibility: A Road Map … 57

Liberty

Harm and Measurement: Preferentist and Non-Preferentist Approaches

Preferentist Approaches and Evidence

Free Disposal and the Imaginary Survey

Revealed Preference in Non-Suicidal Behavior

Non-Preferentist Approaches

Naive Weighing

Benatar’s Asymmetry

Shiffrin’s Asymmetries

Uncertainty

Chapter Ten: The Mathematics of Misery … 68

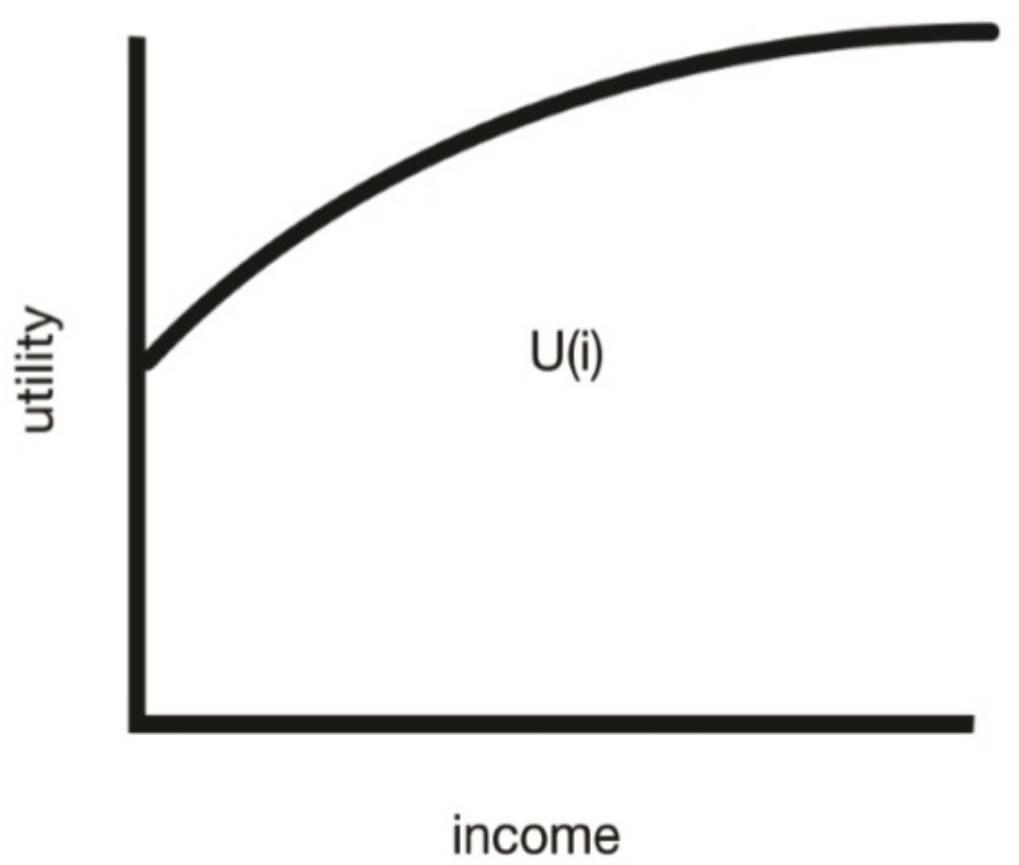

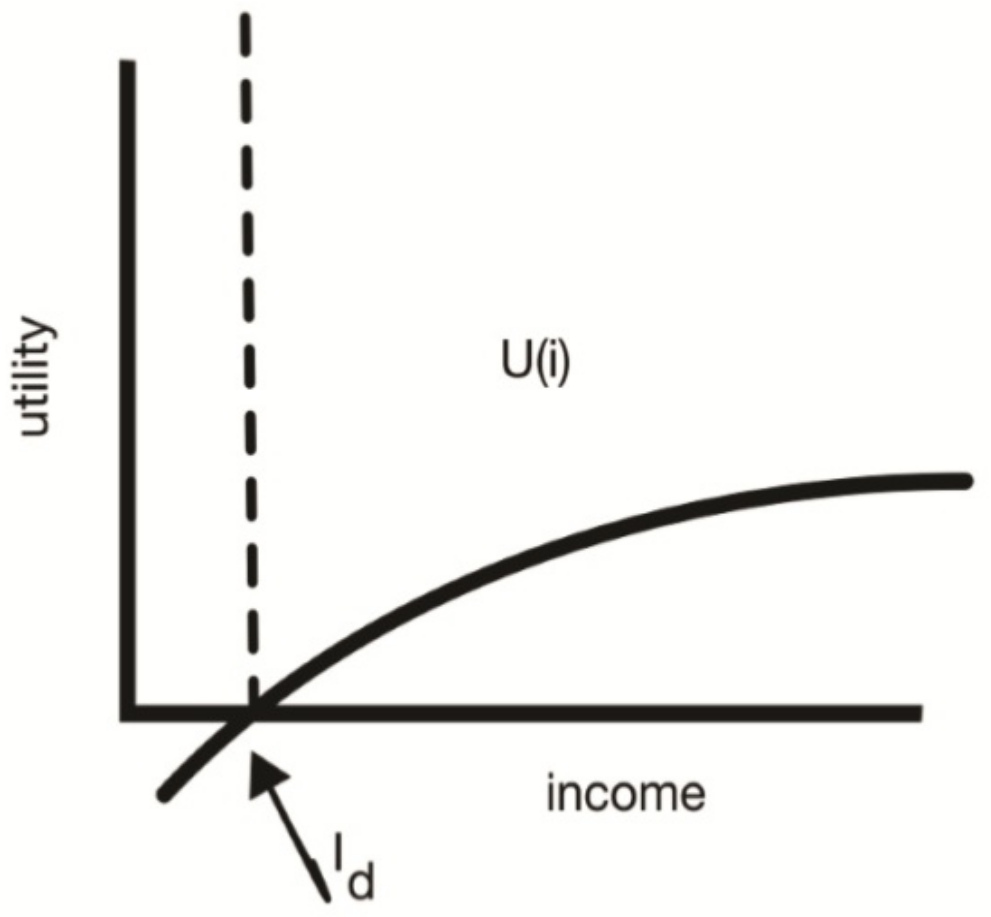

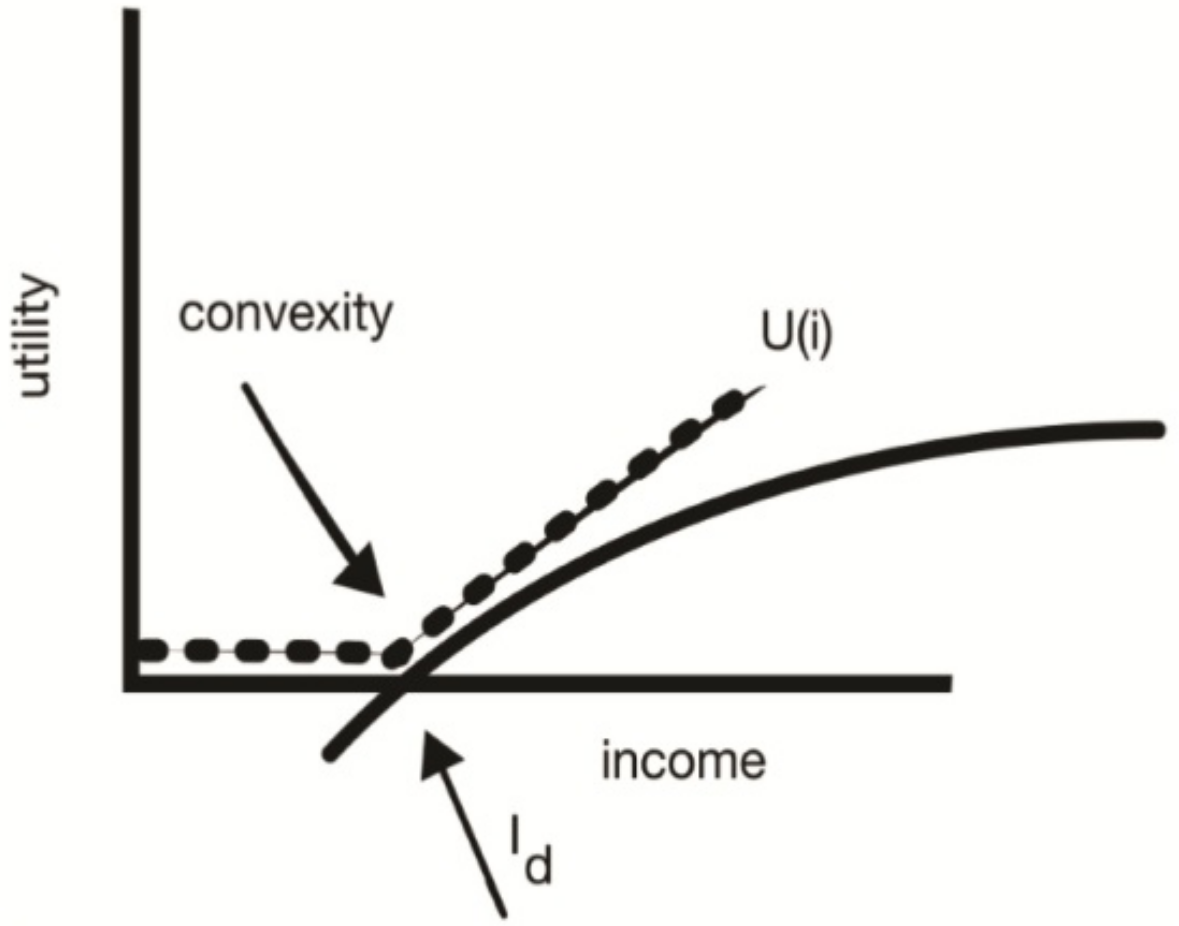

Truncated Utility Functions and the Value of Life

Negative Utility and the Death Wish Economy

Policy Implications

What Real Human Utility Functions Are Functions Of

Poor Baby or Rich Baby: Which is Worse?

The Economics of Palliation and Bullshit

Chapter Eleven: The Burden of Life … 75

Work and Leisure

Poverty and Pain

The Demand for Pain Relief

Is Loss Aversion Irrational?

A Place for Quantitative Methods

Chapter Twelve: Hurting People and Doing Good … 81

Chapter Thirteen: The World of Nature of Which We Are a Part … 82

1. On The Ways In Which Nature Makes Andrea Yates Look Like June Cleaver

2. The Incoherence of Species-Relative Morality

3. Respect for Species?

4. Use Nature As We Please?

5. Is Being Human-Like Better?

Appendix: Living in the Epilogue: Social Policy as Palliative Care … 88

The Story as a Cognitive Bias

Living in the Epilogue

There Are No Stories In Heaven

The Cheery and the Damned

Palliative Care: A Double Standard for People in the Epilogue

Toward Social Policy as Palliative Care

This is a book about ethics. People don’t often change their minds about ethics. When they do, it is generally for social reasons, not because they are exposed to reasoned argument. Reasoned arguments more often allow people to cement their existing opinions. Ethical beliefs are, in any case, extremely limited in their ability to influence actions.

I will advocate several ethical positions that are counterintuitive, and that some people would describe as evil. These ethical positions include the view that life—not just human life, but all life capable of having experiences—is very bad. It is very immoral, I will argue, to have babies or to otherwise create aware beings. I will also argue that suicide is not wrong or a product of mental illness, but an ethically privileged, rational response to the badness of life.

You might imagine these to be positions held by a comic book villain bent on destroying all life in the universe for its own good. That’s fine with me. In fact, it’s a good place to start. Because in presenting what I hope is a reasoned and factually supported ethical argument advocating such extreme ideas, I do not expect to persuade. It is more likely that I will be mentally categorized by the reader as such a cartoon villain (assuming the reader is not one of those few to whom these cartoon villain ideas seem obviously right). And to the extent that the reader holds contrary, prolife, anti-suicide beliefs, I understand that exposure to my unorthodox views may only reinforce those beliefs.

Believe it or not, that seems pretty rational to me. To respond to crazy-sounding out-group beliefs with increased faith in the in-group beliefs validated by known and trusted authority—is a smart strategy. From the trenches of interpersonal communication, I don’t think “ad hominem” is even much of a fallacy. On the contrary, consciousness—and all knowledge—is social in nature; and most of our knowledge comes not from direct experience or through reasoning, but from trusted sources. Though some of our beliefs about the physical world come from direct experience, we mostly rely on the trusted testimony of teachers, scientists, and friends to understand such things that we have no direct experience of, or of which our direct experience is understood to be limited or mistaken. The Earth appears to be flat, and the sun, which looks like it is smaller than the Earth, appears to be moving around the earth. We know better only because we are reliably advised that our initial sensory impressions are incorrect. In a similar way, we get some of our ethical beliefs from direct intuitive perception, but we also rely on the ethical beliefs of those around us to shape our own beliefs and actions. We are much more likely to be vegetarians if our friends are vegetarians. We are much less likely to support gun control if our friends are gun enthusiasts.

Many readers will find it natural to think of the self as the ultimate arbiter of ethical questions, but this is based on a modern and distinctly Western conception of the self. And even self-heavy moderns will sometimes admit to confusion as to what is the right thing to do in a morally unclear situation. Who, then, is to be consulted and trusted on issues of moral relevance? And what should be the result if one disagrees with a trusted friend on a moral matter?

There are some people—crazy people, evil people, people who have taken large amounts of methamphetamines for days on end—whose disagreements with our opinions on ethical matters would not cause us to have any doubts as to the correctness of our own opinions (possibly the opposite, as noted above). But any socially well-adjusted human being is likely from time to time to encounter a person whose contrary opinions are less easily dismissed. When we engage with such a person—who is so trusted, whose mental apparatus has been so verified to work well, and whose motives are so clearly earnest—we may come away less certain about the correctness of our own views. I like the term “epistemic peer” for a person so trusted, brain-wise and team-wise, that his opinion will be taken very seriously when it disagrees with our own.

I am more interested in establishing myself as an epistemic peer of the reader than in autistically presenting a logical argument for the correctness of my views. When you find yourself coming to an unusual conclusion and you can’t find a flaw in your own reasoning, the epistemically proper path, I think, is to show your brain and show your work. You display the way your mind (your laboratory apparatus) approaches the problem, and you present your argument (your laboratory protocol) in a clear way so that others may examine it.

As I would rather participate in social reasoning than table-pound in my corner, I will not only present the extreme forms of my arguments (many of which I think are correct); I will also attempt to present the continuum for each position, many points along which are uncontroversially reasonable. More important, I will show that such continua exist. I consider many people reasonable who do not go full cartoon villain and agree with me that all life is unfortunate and nobody should ever have babies. What makes such people seem reasonable to me is that they recognize the possibility that a given life could go very badly, and that the joys of life might not outweigh the suffering. At the very least, they recognize that the interests of an aware being are very hard to predict before that being is created.

What I would like readers of this book to come away with is not the urge to bomb IVF clinics or dismantle suicide barriers on bridges. I would prefer that readers simply and sincerely consider the question of whether existence is a blessing or a burden, and I hope to encourage the understanding that for many people, it is a useless burden. I would like the reader to think of parenthood as a moral decision affecting a new human being, rather than an event that merely happens to oneself. I would like the reader to consider that it may be both more important and more possible to prevent harm than to do active good in the world. I would like readers to consider the mental states of aware beings as being a very important, if not terminal, locus of ethical value in the universe. Finally, I would like readers to dig further into the nature of their own values, especially the primitive values of survival and longevity. If these points are communicated, I will have done my duty to the late Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who suffered much in his life for the good of others and who, before his death, kindly gave me permission to use one of his paintings on the cover of my book.

The prevailing views on birth and suicide, I will argue, are very misguided. But they are misguided in characteristically human and evolutionarily adaptive ways. In order to reject them, we must approach what David Eubanks has called the Frontier of Occam—the highest intelligence achievable by a civilization before it figures out better ways to achieve its ends than by continuing to pursue the goals of its alien creator, evolution.

I suspect that I have made more converts to the cause of questioning life’s value simply by being an adorable housewife who makes a killer chanterelle risotto than by any particular argument I’ve constructed. Since I can’t make you risotto, I have tried to present my arguments in a calm and reasoned manner, with abiding respect for the humanity that we all share. Perhaps I will come across as the sort of cartoon villain you should accept as an epistemic peer. But whether or not you allow me to influence you with my dangerous ideas, I hope you will believe me when I tell you that I am very much on your side. You are, after all, an aware being having experiences. This is true whether or not you have had or will have children, and this is true whether you want to live or want to die.

Thank you for reading my book.

I would like to thank Chip Smith of Nine-Banded Books for bringing this book into existence over the past four years, for suggesting that I write it, and for encouragement, technical assistance, and friendship along the way. Thanks to everyone who has read early versions of this book and provided helpful criticism and editing assistance—Thomas Ligotti, Ann Sterzinger, Jim Crawford, Anita Dalton, Samuel Crowell and Sam Frank, among others.

Thanks to Rob Sica for his philosophy scholarship and librarian assistance, and to readers and commenters of my blog. Thanks to my family, Nona Perry, Dan Perry, Nona Baker, Michelle Perry, Gleta and George Perry, and Kris and George Perry; and to my husband, Andrew Breese, for supporting my work and exploring ideas with me; and to my friends Sarah Lennon, Megan Robb, Phil Ogston, and C. Thi Nguyen. I would like to thank the late Dr. Jack Kevorkian for permission to use his evocative painting as cover art. Finally, I would like to thank Unaffiliated Smartypants Twitter for engaging with crazy ideas with me over the past few years (which acknowledgment is not meant to suggest that such a thing as Unaffiliated Smartypants Twitter exists).

|

Credit: Joshua Zader

Sarah Perry is a housewife in San Antonio, Texas. This is her first book.

Copyright

Every Cradle Is A Grave

Rethinking the Ethics of Birth and Suicide

Sarah Perry

Copyright © 2014

Published by Nine-Banded Books, PO Box 1862, Charleston, WV 25327, USA

NineBandedBooks.com

ISBN-10: 0989697290

ISBN-13: 978-0989697293

Cover painting: Very Still Life by Dr. Jack Kevorkian (1928–2011)

Cover design by Kevin I. Slaughter

When people are considering whether to have a child, is it appropriate for them to consider whether the child might be harmed just by being created? Should they think about whether life for this child might be a great burden, rather than a gift?

In a blog post entitled “Free Disposal,” economist Bryan Caplan says that it is not appropriate to consider such things.1 We can see that life is always a blessing and never a burden, he says, because people may freely dispose of their lives if they wish, but few take advantage of this opportunity. By revealed preference—an economic term for a person’s actions revealing his true desires—it is clear that people overwhelmingly find their lives to be of positive value.

Caplan writes:

Actually, this may well be the easiest utility inference in the world. We know that people almost universally prefer existing to not existing because there are so many cheap and easy ways to stop existing.

As intro econ teachers might say, life is a good with free (or nearly free) disposal.

To bolster his position, Caplan cites the following passage by Epicurus:

Yet much worse still is the man who says it is good not to be born, but “once born make haste to pass the gates of Death.” [Theognis, 427]

For if he says this from conviction why does he not pass away out of life? For it is open to him to do so, if he had firmly made up his mind to this. But if he speaks in jest, his words are idle among men who cannot receive them.

In another blog post entitled “A Cursory Rejection of Antinatalism,”2 Caplan makes a similar claim:

Almost everyone’s behavior confirms that they’re glad to be alive. After all, no mobile adult needs to be miserable for long. Tall buildings and other routes to painless suicide are all around us; in economic jargon, life is a good with virtually ‘free disposal.’ Yet suicide is incredibly rare nonetheless.

Bryan Caplan believes that we live in the Land of Free Disposal. We do not. While legal in a narrow sense, suicide is still very much the subject of prohibition. The costs of making a serious suicide attempt are actually very high, and prohibition increases these costs. In this chapter, we will explore the suicide prohibition and the costs of suicide, and then imagine a world very different from our own—the Land of Free Disposal, where suicide is not meaningfully prohibited and the costs of making a serious suicide attempt are actually minimized. It might not be a nice place to visit, but it is certainly not the world we live in.

In the United States, a person is not guilty of a crime for attempting to kill himself. This is the only sense in which suicide is legal in the modern Western world. The first sense in which suicide is prohibited is that a person may be imprisoned against his will in a hospital for attempting suicide. If a person is judged to pose a danger to himself, such as by attempting suicide or even expressing the desire to commit suicide, he may be held against his will on the locked ward of a psychiatric hospital. The length of the legal period of incarceration varies by jurisdiction.

Once on the locked ward, the patient is not free to leave; guards, alarmed doors, and other measures are in place to prevent him from “eloping.” If he has attempted suicide, or is suspected of harboring suicidal thoughts, he may be obliged to remove his jewelry and clothing and be forced to wear paper clothing instead (paper clothing poses less of a hanging risk). Staff may watch him while he sleeps, through a suicide watch window. He will be monitored while he shaves, if he is allowed to shave.

Freedom is an imprecise term. But when the government authorizes the imprisonment of a person for attempting or even seriously discussing a particular action, it seems natural to conclude that he is not free to do that action. The person contemplating suicide has more to fear from the hospital than from incarceration. If he survives his suicide attempt or is discovered before he has died, then a progression of paramedics, nurses, doctors, and perhaps even surgeons will attempt to foil his plans by saving his life. Even people who choose very lethal methods by which to exit the world, such as a jump from heights or a gunshot to the head, frequently fail to end their lives, in large part due to modern medicine.

Across the United States, four billion dollars are spent annually on emergency room and hospital treatment for people who attempted suicide but were caught before they could die. A person is not “free” to do something that he must either get away with in secret or be forcibly prevented from doing if caught.

It gets worse. Those brought back from the brink of death often suffer debilitating injuries that significantly decrease quality of life—below a baseline that was already not worth living. One such patient was the focus of a 2007 single-patient study in the Annals of Neurology.3

The patient, a 48-year-old woman, had at that time been kept alive for over two years in a state of akinetic mutism—she was conscious, but could not move or speak. She experienced severe brain damage from a suicide attempt and was kept alive for years while scientists performed experiments on her. She may be alive still.

Life may not be disposed of freely if those who attempt to dispose of it are routinely “rescued” and brought back to life. The policy makes successful disposal less likely, and the risk of being preserved alive in a maimed condition increases the cost of a suicide attempt.

And those tall buildings that are supposed to provide for the free disposal of life do not work very reliably. Even the jump from the 64-meter Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul fails to result in death around 3% of the time. A gunshot to the head is similarly risky, and methods like slashing arteries, hanging, or suffocation by automobile exhaust are even more likely to fail. More important, these methods are horrible; the need to endure the experience makes the cost of the attempt very high. Aversion to heights and body envelope violation are installed by evolution and difficult to overcome, even for people who truly desire death.

An observation an economist might make is that methods of suicide are not good substitutes for each other. When a popular method of suicide is made illegal or more difficult, the overall suicide rate often goes down; people do not simply substitute a different method of suicide. After Australia tightened motor vehicle exhaust restrictions, making suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning more difficult, the regional suicide rate decreased. Suicide attempts using this method remained popular but became less lethal, resulting in fewer suicides. More impressively, a few studies of suicide barriers on bridges have found that installing a suicide barrier on a bridge does not increase suicides from nearby bridges. Gun ownership increases the risk of suicide; the availability of a method that is fairly reliably lethal confers such a reduction in the cost of suicide that merely owning a gun makes one more likely to commit suicide. One of the most universal findings about suicide is that men successfully commit suicide about four times more often than women; but where methods preferred by women are available, such as the lethal poisons that may be ingested by mouth that are available in China and India, the female suicide rate sometimes exceeds that of men! People do not seem to freely substitute one method for another.

Low rates of substitution indicate that for disposal to be free, desirable methods must not be restricted. And there is a clear, best method. It is reliable, reasonably free from pain, and does not require the suicide to endure a frightening body envelope violation or similar trauma. In those jurisdictions in which suicide is legal under limited circumstances for humane reasons, this is the method used. This is the method preferred by doctors, nurses, veterinarians, and others with relevant knowledge and the ability to acquire the means. This method is, of course, a drug overdose, either by barbiturates or by a synthetic opiate like Fentanyl.

The drug prohibition (or drug war) means that barbiturates and Fentanyl are not legally available to people who wish to use the best method to commit suicide. If the best method of disposal requires committing a crime, even though it hurts no one, then disposal is hardly free.

In our interconnected market society, it is difficult to do anything alone, with no one’s help. Suicide is a particularly difficult task, and the resources, information, and assistance provided by another person might make the difference between success and failure. Such assistance is illegal.

Helping another person to commit suicide is prosecuted as a crime in all but the most limited situations in the few states that allow physician-assisted suicide. Suicide is the only act that is not itself a crime, but which assisting another person to commit is a crime. Even trying to die together may be interpreted as assistance for prosecutorial purposes; the survivor of a suicide pact has sometimes been prosecuted for the death of his luckier comrade.

To forbid assistance makes the act less free. The suicidal person is not only prevented from enlisting friendly volunteers to help him, he is denied the ability to freely use markets to achieve his ends. This is a severe handicap indeed, because of both the power of the market and the impotence of the disconnected individual.

And so we might amend Bryan Caplan’s confident assertion thus: Disposal is free—except that you will be locked up in a hospital if you are caught trying to exercise this freedom; except that your unwanted life will be returned to you if possible, perhaps in worse condition than before; except that you may not use the most painless, reliable method that puts no bystanders at risk, but must take your chances with painful, violent methods. And no one may help you.

If disposal is not “free” in the sense that it is legally permissible, it is also not “free” in terms of costs. We will now look at some of the costs facing a person considering a suicide attempt.

So far, we have seen that a major downside to a suicide attempt is the risk that it will fail or be discovered before it is complete. The risk of ending up on a locked ward of a psychiatric hospital, perhaps grievously and permanently injured, is one kind of cost of disposal. But there are many.

From the gene’s-eye perspective of evolution, it is very dangerous for an organism to have the capacity to realize that it can escape all of its pain and sorrow by ending its own life. If an organism is given this capacity, either it must be kept content enough that it never wishes to commit suicide, or it must be inhibited from committing suicide, physically or psychologically.4 Many of the costs of a suicide attempt stem from these built-in inhibitions. The terror that a person feels, standing on a bridge or on top of a high building, desperately wishing for death and trying to summon the courage to jump, is an example of the psychological inhibition against suicide. The universal disgust response to body envelope violations is another; it is psychologically trying for a person to cut through all the skin, muscles, and tendons necessary to access his arteries. Passing out from low oxygen and vomiting when poisoned are examples of built-in physical barriers that sometimes effectively inhibit suicide.

But people do not exist as individual units separate from human relationships and groups. A great deal of the cost of committing suicide faced by a person wanting to die is social and empathetic: it is resonant in the loneliness and grief that his death will cause, or at least hasten, among parents, children, siblings, a spouse, or friends. As social creatures, we begin forming bonds at least as soon as we are born; these bonds, while often no more voluntarily chosen than our own births, are powerful motivations. Those with whom we have formed social bonds rely on us, imposing a significant cost on suicide even for a miserable person who genuinely wishes to die.

The person who successfully ends his life deprives his relatives and his friends of his continued company and support. Everyone dies eventually—the grief and deprivation that death entails are inescapable—but the suicide hastens death, and so appears responsible for it in the eyes of his community. And it is not just the loss of company and support. The suicide of a close associate is usually regarded as much more painful than the event of such a person moving across the country and losing touch, even though the deprivation is similar in either case. Some social costs are artifacts of the prohibition. The suicide must act in secret, sneaking and hiding to avoid detection and unwanted rescue. But who will discover his dead body? It will be especially traumatic for a relative or close friend to happen upon the dead body of a suicide. But often the other option is to risk not being discovered for a long period of time, during which those close relatives will need to endure the fear and uncertainty of “missing person” status. And because of the prohibition, the person determined to commit suicide cannot calmly discuss his intention with his close associates. He cannot say goodbye, or he will likely be locked up in a hospital. Part of what makes suicide seem devastating for those left behind is that it is framed as a tragic, preventable loss rather than the lucky escape of a miserable person.

The presence or absence of strong social bonds is actually more determinative of suicide than misery or suffering. Thomas Joiner, in his influential study of suicide,5 found that failed social belonging—and, to a lesser extent, a sense of burdensomeness rather than helpfulness—is a better predictor of suicide than any other kind of unhappiness or misery. The only other strong predictor of suicide in his model is the competence necessary to use one’s chosen method, i.e. access to drugs, knowledge of guns, etc.

Unhappy countries do not experience more suicide than happy countries. A major study recently found that countries with higher levels of happiness actually have higher suicide rates than less happy countries.6 (This finding was replicated at the level of individual states of the United States.7) Simple misery does not seem to reliably cause suicide, the way it would in Bryan Caplan’s naive model; rather, people seem to commit suicide when they are freed from, or perhaps rather deprived of, the social bonds that were keeping them alive.

There are significant costs associated with suicide apart from the loss of one’s life, and when these costs are removed (whether by weakening social bonds or making desirable methods available), suicide is made more likely. It does not seem to be the case that people are avoiding suicide simply because they are happy to be alive.

Bryan Caplan’s assertion that creating lives can never be wrong because we live in a world with many tall buildings to jump off of (yet only a small proportion of humans actually utilize these free disposal services) is based on a faulty understanding of reality. But what would Caplan’s ideal Land of Free Disposal look like? We turn now to imagining such a land in which suicide is really free—in which legal barriers to suicide are removed, and in which people are permitted to subvert the natural (but unwanted) barriers to suicide.

This imaginary land does not necessarily represent my policy prescriptions (for instance, I think parents lose their moral right to commit suicide when they take on the responsibility for a child), and we will find it is not a utopia. The thought experiment is meant to illustrate the high cost our own world places on “disposal,” and how this cost is related to the burden of having been born.

In the Land of Free Disposal, the main guiding intention is that it is easy to commit suicide. When a person makes a suicide attempt, he is not sent to a hospital prison; instead, if he has followed proper procedures for signaling his intention, he dies. The most lethal, comfortable methods are widely available, and since suicide is fine, a competitive market arises to provide the most appealing methods. The power of the market is brought to bear on the problem of finding desirable ways to die. Not just “Ask your doctor if Obliviall is right for you,” but also death arcades.

The technological burdens of suicide are taken care of in the Land of Free Disposal. The market is a powerful instrument, and allowing it to solve the problems of suicide makes disposal relatively comfortable and efficient. No one has to cut his arteries or shoot himself fourteen times with a .22. Only rarely does someone jump off of a tall building. Suicide is easy, painless, and guaranteed.

Technology can go a long way toward undermining our unchosen, Nature-programmed, often irrational fixation on our own continued existence. Of course, it is unlikely to completely free a human being of the biological costs of disposal, but in the Land of Free Disposal these costs are at least minimized.

But the technology is not everything. The guarantee of death is very important, perhaps more important than the technological aspect. Even a small possibility of surviving a suicide attempt, in maimed and helpless condition, is rationally a major concern. If one is at all tempted toward a Many Worlds8 analogy for probability, after a good, strong suicide attempt, most of the future selves are gone—but a few, the only conscious ones, are trapped in a hospital incommunicado for decades. Even if the probability is very tiny, the potential consequences are so bad that it may not be worth the gamble. But no one needs to worry about this in the Land of Free Disposal.

So everyone who wants to die may die. But to ensure that disposal is truly free, other costs must be removed from the suicide as well. Suicide has no stigma in the Land of Free Disposal. In kindergarten your kid’s teacher has each student draw a picture on the topic of “When Would I Kill Myself?” What has he drawn there? It is very sad when children commit suicide—and many of them do, even in our world—but preventing them from doing so is not free disposal.

Many people do not want to die alone. As in our world, people sometimes post pictures of their last moments to Facebook, but in the Land of Free Disposal the pictures are taken automatically at the death arcades and resemble on-ride photography at Disneyland. In this way and in many other ways, the path to death is made easier by the possibility of social connection. Unlike in our world, people in the Land of Free Disposal may sit with a dying suicide to comfort and even assist him without fear of imprisonment.

The desire for some kind of connection to the future after one’s death—a kind of immortality—is recognized as a strong psychological motivation, and provided for in the public policy allowing suicides to donate their organs at a hospital. There is no organ shortage in the Land of Free Disposal, and since suicide isn’t creepy at all, everybody wins.

There have been changes in lending and credit, and in contract law in general, in the Land of Free Disposal, but institutions have adjusted. Standard clauses have been drafted to amend insurance policies and other formal agreements.

Of course, the loneliness of family and friends must be considered a cost of suicide not likely to be attenuated by social interventions. We may not wish to reduce these bonds—to do so might create a very undesirable society—but they form a cost of suicide that may make a person suffer through a miserable, unwanted life for the good of others. The Land of Free Disposal might experiment with weakening social bonds through alternative methods of childrearing, as with kibbutzim, or alternative relationship structures, such as arm’s-length polyamory rather than mutually dependent monogamy. Policies designed to reduce interdependence between humans might make suicide easier for those who desire it, but to the extent they are successful, they would also likely reduce the aggregate quality of life experienced by everyone. A social species like ours is unlikely to achieve truly Free Disposal, except perhaps among our most isolated members. But other interventions could at least partially balance the burdens that social bonds place on the person desiring to be rid of his existence.

A posthumous tax credit for suicides, for example, might decrease the socially-imposed cost of suicide for a miserable person. And rather than spending tens of millions on suicide prevention efforts (as our government does through the National Institutes of Health, the military, and other agencies), the governing body of the Land of Free Disposal spends money on campaigns to promote the right to suicide. In the Land of Free Disposal, billboards, television, and the Internet carry the message that suicide is a sacred right, rather than the message that suicide is wrong and a sign of illness. PSAs remind people that “No One Owns You—Suicide is Your Right!” On the chance that suicide “contagion” is real and social proof removes a major cost of suicide, fictional and nonfictional accounts of successful suicides are broadcast widely in approving terms. Curricula in schools emphasize personal autonomy, vilify interpersonal possessiveness, and treat suicide as a positive life choice to be seriously considered. “Do You Love Her Enough to Let Her Go?”

The distance between the Land of Free Disposal and our own world is a measure of the burden of life placed on anyone born into our society. In our world, only about a million people a year successfully commit suicide; in the absence of restrictions and costs, this number would be much higher. Bryan Caplan’s “easiest utility inference in the world” is, as we have seen, incorrect. Creating a person places a burden on him that he may be obliged to bear against his genuine desire to be rid of it. Creating children in a cavalier and thoughtless manner is not a morally responsible option. We must look deeper to determine whether creating a particular child is in that child’s best interests.

Even the best human lives include substantial suffering. A typical person experiences considerable pain, loneliness, and boredom in his lifetime, together with aging and the inevitability of death. What is it that justifies the human species in reproducing itself despite all the suffering?

One possible answer is the happiness and pleasure that life is expected to provide, and this happiness-and-pleasure hypothesis will be treated seriously in later chapters. But happiness is not the reason most people feel that life is valuable despite all the suffering; rather, it is meaning. The feeling that life is meaningful is the real reason that people think human lives are worth making. The conviction of meaning functions as an intuitive justification for creating the lives of others; whether or not this justification is valid, it does seem to be true that finding a sense of meaning eases the experience of suffering in actual lives.

Subjectively, the feeling that life is meaningful—that there are ultimate values, that life has a purpose—tends to point to a source of meaning, something higher than and external to the mere feeling or intuition of meaning. While sources of meaning vary greatly (and often contradict each other), the sense and expectation of meaning itself is surprisingly universal—so universal that the intuition is almost never challenged.

This very universality should motivate us to be cautious about taking meaning’s claims at face value. One should be suspicious of any claim that is defended for contradictory reasons, and most people who agree that life is meaningful disagree as to what makes it so. The belief that life is meaningful tends to take the form of a strong feeling rather than a reasoned conclusion; indeed, one of the functions of meaning is to shield a person from the harmful effects of reasoning by providing a value that is justified for its own sake, a foundational rock for cognition below which no “whys” need be answered.

It is this feeling of meaning that may be profitably investigated. We will examine the needs that motivate people to seek meaning, then explain the methods used by various sources of meaning to meet those needs. Along the way, we will look at some of the trends in meaning in the rapidly changing modern world from a cultural evolution perspective.

The social psychologist Roy Baumeister has been studying how people experience meaning in their lives for decades, and continues to publish on the topic to this day. His 1991 book Meanings of Life proposed four needs that must be filled with sources of meaning:

- a need for an ultimate value base

- a need for personal purpose

- a need for self-worth or status

- a need for efficacy or control

Both Baumeister’s later work and the work of psychologist Thomas Joiner indicate that a fifth need is also critical for human well-being: the need for social belonging. The satisfaction of this need is crucial for the sense of meaning. Thwarted belonging (through, for example, divorce, job loss, or social rejection) is painful and so destructive of meaning that Thomas Joiner found it to be a major predictor of suicide. It is the social group that maintains sources of meaning most effectively; people are rarely successful at supplying meaning for themselves without outside assistance. Even the ultimate value of the self is most effective when reinforced by the social group.

Human cognition is characterized by asking “why?”—explicitly as a child, internally as an adult. If an action is difficult or undesirable, it must be justified. More general principles justify specific cases. Stop at intersections because it is part of one’s duty to drive carefully; drive carefully to avoid hitting people; avoid hitting people because injuring others through carelessness is wrong. To avoid infinite regression (and all the cognitive trouble that would go along with it), there must be some end to this process of justification: humans need values that are valuable for their own sake, ultimate values not relying on anything else for justification. A value is an end, as opposed to a means to an end, and offers an end to thinking uncomfortable thoughts that have no answer.

Ultimate values may be positive (for example, space exploration, or “the show must go on” in theater) or negative (for example, eschewing racism or adultery as purity violations). They are often experienced as sacred—self-evident, not to be traded off against non-sacred values, and perhaps even surrounded by a protective zone of “motivated ignorance,” as Jonathan Haidt puts it.9 Sacred values may be lost if not protected, and are difficult to recreate once lost.

Successful social belonging has been a prerequisite for survival and reproduction in the human line for millions of years. It is a need on par with the need for food. Indeed, humans in dire poverty often choose to spend money on social belonging rather than on more food. Even minor threats of social rejection cause anxiety and insecurity; one line of research suggests that social rejection hurts like physical pain. Philippe Rochat, in his book Others in Mind,10 calls social rejection the mother of all fears, the driving force behind most higher-order human psychology, particularly the exacerbated human care about reputation and the control of public presentation of the self.

He continues:

I propose that the need to affiliate and its counterpart, the fear of social rejection, together form the bottom line of what underlies the experience of shame, embarrassment, contempt, empathy, hubris, or guilt. This underlies all the powerful and often devastating self-conscious emotions that are presumably unique to our species.

Social groups, rather than individuals, are the units that maintain sacred values. People generally adjust toward accepting the meaning sources of their near peers. Religious people who leave their community have difficulty maintaining old beliefs while surrounded by people with alien values and meaning structures. On the other hand, people with extreme religious beliefs report more happiness than less religious or non-religious people; the religious community provides both a reliable social belonging experience and a solid, clear basis for value whose self-evident truth is made easier to see by interaction with fellow believers.

Isolation is profoundly disturbing, as prisoners detained in solitary confinement learn. Thwarted social belonging predicts suicide, as noted above. People faced with the loss of social belonging (especially stemming from the loss of a job or a romantic partner) are more likely to commit suicide. Those with sources of social belonging, such as a spouse or small children, are less likely to kill themselves.

An important exception that proves this particular rule involves married prisoners. Research has shown that prisoners who were married or employed at the time they were incarcerated are actually more likely to commit suicide than unmarried, unemployed prisoners.11 In this case, the married, employed men experienced prison as a loss of a high level of social belonging in the outside world; unmarried and unemployed prisoners experienced less of a drop in social belonging, and may have even viewed prison as a continuation of previous belonging experiences, such as through participation in gangs.

We rely on each other for belonging, and we rely on each other to maintain the collective sources of meaning. We cannot do these things for ourselves.

The need for purpose is the need for a present idea of something in the future that motivates present action. All the sources of meaning provide ways to spread the self out over time, to consider the past and the future when weighing what to do now. Purposes provide reasons to make costly sacrifices in the present in order to improve the future.

Baumeister12 divides purposes into two types: goals and fulfillments. Goals are short-term future plans that are likely to actually be achieved; once a goal is completed, a new one must be found. Fulfillments, on the other hand, are fantasies about an idealized far future. Eternal life in heaven is an example of a fulfillment, but many fulfillments are not religious in nature. Any goal that seems to offer, in one’s own mind, a permanent state of sustained positive affect, is likely to be a fulfillment rather than a normal goal. These might include fame’s promise of eternal bliss or “making it” in a high-status career, or more mundane matters like marrying or having children, or even the fantasy of “dropping out” and raising organic goat cheese on a farm. In each case, if we cared to look, we would observe that currently famous people, high-status careerists, spouses, parents, and goat farmers are not ecstatically happy all the time—they have goals and fulfillments of their own. In an important way, this is not the point: fulfillments do the job of motivating present behavior as long as they are plausible.

Every aspect of meaning is characterized by illusion. The present self is fooled in order to coordinate its actions. In a later section we will consider who is doing the fooling.

People need to feel that they have control over the world around them, that they have the ability to reach goals or realize values. Efficacy means the capability to help others as well as oneself. Baumeister et al. (2013) found that a greater sense of meaning was associated with doing things for others, even though in many cases happiness was reduced even as meaning was enhanced.13

Loss of efficacy happens naturally with aging. Over time, the faculties and capabilities used to define the self erode. Similarly, disease or paralysis can harm one’s sense of efficacy. Without efficacy, it’s hard not to be a burden on others; the sense of burdensomeness, along with thwarted belonging, are among Joiner’s three predictive factors for suicide. Suicide itself may be pursued in order to restore some amount of efficacy with the act of death.

The need for self-worth is the need to feel that one is valuable and important relative to others. This kind of status is comparative, and is often realized by comparing oneself to those lower in status. Hierarchies provide self-worth of this kind to everyone except those at the very bottom, who must find alternative bases for self-worth. In societies without clear status hierarchies, there is less certainty about social position, hence more worry. In societies whose social system is in upheaval, for example by political or technological revolution, values of each type may be lost. It may be best to have many sources of meaning to rely on, each acting as insurance against the others’ disappearance.

The old sources of meaning are cultural items—items of information that reproduce themselves using humans, in a symbiotic rather than parasitic relationship. The cultural package of religion, morals, dietary rules, and heroic stories is the result of hundreds or thousands of years of environmentally attuned replication and refinement. Old sources of meaning have a deserved prestige: they have been proven to work in the environments in which they appear for as long as they’ve been around. They represent the social capital investments made by the group’s ancestors over generations. But when the environment is changing quickly, old values may no longer fit the new conditions; conservative value-maintenance processes may not be enough to control the decline of old sources of meaning.

How can you recover lost values? Deep, effective value justifications are rare, and if lost, may not be replaced. Generally, when faced with the loss of a value, people act very conservatively; rather than seeking radically new kinds of value, they seek to elaborate on an existing value.

In recent decades, faced with the loss of old sources of meaning such as religion, consensus morality, and neighborhood belonging, and lacking a value justification, the existing value of self-worth began to play a greater role in carrying meaning. Prior to the nineteenth century, the self had been commonly regarded as a very bad thing, the enemy of God and of the interests of the group. But gradually, as the foundational bases for value crumbled during the twentieth century, the self, rehabilitated, took on the role of value justification and became the seat of self-worth.

The heavy modern self has a hard task: it must do for itself what human religion and community did in the past. It must provide itself with meaning. Individual selves have been appointed to authorize morality after consensus morality lost its power to coordinate groups. Marriages began to be expected to be a source of personal fulfillment to the individuals involved. Opinions on divorce changed drastically during the 1960s and 70s; what started as an unthinkable act under all but the worst circumstances became a common practice, understood to be sometimes necessary in order to be true to oneself.

Millennials, the most recent generation to come of age in America, have grown up attempting to define meaning for themselves in this strange post-value world. Not surprisingly, opinion polls find them to be selfish and obsessed with fame. Having grown up with only the self to look to for guidance, they have elaborated the only source of value they know.

Meaning takes many forms and operates in counterintuitive ways. Rather than exploring entirely new domains from which to derive meaning, people tend to stick with what they know, elaborating or reinforcing old sources of meaning.

Mothers in prison for killing their children are a particularly meaning-deprived group.14 They have lost a great degree of social belonging. Their self-worth is very low, especially when measured against the role of “mother.” Their efficacy is limited, and they cannot find a justification for their actions. In one survey of such women, nearly every one preferred the same path toward a reunion with meaning, at least in her own mind: almost every mother wanted to have another child as soon as she got out of prison, so that she could prove (especially to herself) that she could raise a child properly and regain her self-worth as a good mother.

People tend not to seek out radical new sources of meaning; when meaning is lost, they attempt to restore old sources of meaning, no matter how much this risks encountering the same harm that occurred before.

Genuinely new sources of meaning do appear from time to time, with varying success at providing for people’s needs. Science and space exploration are new sources of meaning, sacralized decades ago but still closely protected in online social networks. Science is especially seen as a sacred value of liberalism in America, although certain aspects of science (such as psychometric research) conflict with other, more sacred values.

Medicine is a new sacred value, especially since the invention of antibiotics gave doctors a genuinely effective tool in the 1940s. Medicine is implicitly based on another sacred value, science. Health is an acceptable value for a modern who is excessively dependent on the self for value; focusing on health provides goals or even fulfillments (the imagined endless elation when a weight-loss goal is attained) and efficacy, while preserving the self as both a value base and a seat of self-worth.

The heavy modern self, expected to provide its own meaning, seeks to escape meaning when messages about the self are painful. Yet another popular new method of obtaining meaning is to identify with, or loyally fight on the side of, people who are in some manner oppressed. Old oppressed groups are mostly still around (except for the satanic ritual abuse victims, who finally had to leave), and more importantly, new oppressed groups are constantly being discovered. These groups often turn out to have value bases in and of themselves, offering ultimate value, social belonging, efficacy, and self-worth.

Meaning in all the forms above is socially transmissible. The social group itself is powerful; group expectations can prompt behavior that an individual cannot perform on his own. In her book on religious glossolalia, Speaking in Tongues,15 Felicitas Goodman notes that her subjects could only enter a glossolalic trance in the presence of others, and the bigger and more committed the group, the more powerful the effect. You can’t make yourself speak in tongues, but being among others who believe you will speak in tongues can induce that experience. The group’s familiar presence induces a powerful disinhibition unavailable to a lone person. Meaning operates in a similar manner: as a form of social cognition. A person integrating into a new group will absorb many of the new group’s meanings and values. Group membership affects individual values and has for all time; modern geographic mobility means that individual values have recently begun to affect group membership as well.

A moral: be careful whom you accept as an in-group member, as you will almost certainly absorb some of his values.

Sources of meaning display false permanence. They appear to be stable, unchanging, and permanent, but this is one of many illusions involving meaning. In reality, the scrappy source of meaning must adapt and change to survive, or risk disappearing; both its stability and its permanence are illusions.

Fulfillments are especially burdened by false permanence, promising eternal positive affect and endlessly satisfying high status. The stability of value bases is often exaggerated, such as with modern marriage relationships. Modern young people are starved for meaning and crave to attach it to themselves permanently, but tattoos and expensive weddings, sadly, can’t put back together what no-fault divorce has torn apart.

Happiness and meaning are correlated.16 Meaning does seem to contribute to happiness and ease suffering. There are many factors, however, that are correlated to meaning but not to happiness. Experiencing many bad events, for instance, predicts a sense of meaning but also unhappiness. Anxiety is also positively correlated with meaning but negatively correlated with happiness.

Meaning increases with certain kinds of suffering; the meaningfulness of a particular group or experience is proportional to the suffering incurred to join. More intense initiation or hazing rituals create more meaningful bonds within the group. More demanding or more religious utopian communes tend to last longer than their more easy-going or secular brethren.

The experience of meaning in proportion to negative experiences is somewhat malleable. When people are reminded of the costly, negative aspects of a source of meaning, such as the high economic cost of children,17 their evaluation of the source of meaning becomes more positive and more meaningful in comparison with people who are given a more positive spin on childrearing. Meaning appears in proportion to the suffering that occasions it, and meaning can quickly smooth over uncomfortable inconsistencies revealed in one’s worldview. From the outside, it appears to be an illusion; from the inside, it is experienced as powerful and profound.

Some sources of meaning provide actual control over the world and one’s circumstances. Some only provide the illusion of control,18 which may be just as good.

In 1969, researchers tested stress responses to loud noises. Subjects who were blasted with loud noise found the experience very distressing. In one group, however, each participant was given a button; this button, they were told, would turn off the noise if it got too bad. None of these subjects used their button (which wasn’t plugged in anyway), but they mostly felt a lot better about the noise.

Shamans, witches, and even medical doctors often provide an illusion of control to suffering people. A love spell or a bottle of cholesterol pills probably won’t have much real-world effect, but such props can provide a much-needed sense of control to a suffering person.

Life, perhaps, would be more enjoyable and less miserable if it were not mandatory.

When meaning takes the form of a narrative, this is another illusion, though again perhaps a benevolent one. Narratives help us organize the past according to the needs of a present self. The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves also help us plan for the future, as with goals and fulfillments.

There is one particular story that is among our most resilient pieces of cultural information. It arises spontaneously on all continents at various times, and quickly spreads. Depending on its specifics and its messenger, this story can facilitate a revolution or it can protect the status quo. The story is the one about bad people doing bad things, and how they are responsible for the problems in the world. These bad people must be rooted out and stopped for the sake of the country and—often quite literally—the children. A folklore term for this kind of story is a “subversion myth.” Historical examples abound; here are a few from Jeffrey S. Victor’s paper19 “Satanic Cult Rumors as Contemporary Legend”:

In Ancient Rome, the stories commonly claimed that Christians were kidnapping Roman children for use in secret ritual sacrifices. Later, during the Middle Ages, the stories claimed that Christian children were being kidnapped by Jews, again for use in secret ritual sacrifices…In France, just before the French Revolution, similar stories accused aristocrats of kidnapping the children of the poor, for use of their blood in medical baths. [Citations omitted.]

Police in modern Saudi Arabia routinely hunt, arrest, prosecute, and execute witches. In the early 1980s, Christian religious programming on state-run television in Benin, Nigeria, generally condemned Western influence and blamed the country’s problems on corruption and witchcraft.20

The Benin example highlights that the vilified class need not exist in reality for the story to be effective, as with the satanic cult ritual abuse panics of the 1980s and to some extent the modern wars on terror and bigotry. What makes the story of bad guys so popular? Mainly, it provides a universally applicable justification for why things are not going well. In human societies, things are generally not going well in a variety of ways, at least from the perspective of individual members. But subversion myths arise in times of special trouble; as Victor puts it, they “usually arise at times when a society is undergoing a deep cultural crisis of values, after a period of very rapid social change has caused much disorganization and widespread social stress.”

This justification for things not going well satisfies people’s need for an explanation. A story that vilifies those in power may precede (and perhaps precipitate) a revolution, as in France. Revolutions are particularly likely to occur when things are really, really not going well in a society in the first place, hence there is a great perceived need for an explanation.

A story that vilifies others, however, is useful once the revolutionaries have seized power and become the government, with an interest in maintaining the status quo. When religious movements like Islamism, democracy, Christianity, and communism first come into power, things are generally pretty bad; the new government has something like regression to the mean on its side. Unfortunately, political societies are delicate, carefully evolved systems and it’s amazing that they limp along at all; attempts at reform, like mutations in DNA, usually make things worse. Yet the story offers hope. Millions of scapegoats have been executed by governments in service of this story.

Despite its flaws, the story is certainly more comfortable than suddenly accepting that large human societies just can’t be very good or wise or fair or free, and that attempts to manipulate the intricate yet lumbering social ecosystem, no matter how well-meaning and carefully researched, usually make things worse.

A final illusion that meaning creates is one of particular specialness with regard to the source of meaning. People get attached to sources of meaning and regard them as irreplaceable. Actually, it does not seem to matter what source of meaning appears, as long as one is found.

Sacredness is a universal human phenomenon. Emile Durkheim proposed that religion operates in all human societies, whether visibly or not: wherever there is a moral community, it will display particular beliefs and practices for the veneration and maintenance of its sacred objects.

Sacredness is often invisible from the inside, but we can see its nature when it changes rapidly over a short period of time. The trajectory of smoking in American culture from the 1980s to the present is a case study in the formation of a modern sacredness. Smoking was common during the middle of the last century—in restaurants, in offices, even on airplanes. But public focus began to be drawn to the harms of smoking, especially cancer. Tobacco companies were vilified for selling deadly products and for hiding their deadly nature; cigarettes themselves absorbed some of this moral indignation. Not only the act of smoking but also images of cigarettes were regulated and prohibited. The proportion of smokers in the United States plummeted over a few decades.

Cigarettes became not just harmful, but ritually impure, a sacredness violation. The prohibition’s magical, religious nature can be seen in the way that cigarettes ritually contaminate activities similar to smoking, but without any of the harm that justified the marginalization of cigarette smoking. Nicotine inhalers have gained popularity in the United States, offering nicotine delivery in a manner functionally similar to smoking, but without any of the carcinogens released by burning tobacco. This practice has been the subject of bans and strict regulation in many states, cities, and private companies. What has happened is that the impure, profane act of cigarette smoking has rubbed off its residue of moral degradation onto the behaviorally similar act of using a nicotine inhaler.

Breastfeeding in the United States has undergone an opposite trajectory. A few decades ago, breastfeeding was an act performed in private, and only in desacralized areas. (My own mother remembers not being allowed to breastfeed in the Mormon church when I was a baby, over thirty years ago.) Public breastfeeding was an unspoken violation, and as such would have been disturbing to witness. However, activist pro-breastfeeding groups such as La Leche League formed networks of new mothers, transmitting pro-breastfeeding ideas from woman to woman, insisting that they conceive of breastfeeding as natural, not sexualized, and not shameful. These ideas are now widely held, even somewhat sacralized, and public breastfeeding is much more common. Employers must accommodate the breastfeeding schedules of their workers. Even the Mormon church now encourages and supports the practice. Criticism of or threats to breastfeeding are now seen as sacredness violations, whereas decades earlier public breastfeeding would have been the shocking violation.

Sacredness illuminates a practice or an object with a halo of righteousness, or casts onto it an aura of contemptibility. It functions to limit the discussion that is permissible surrounding the sacred object, including the nature of its depiction in art and culture. The cognitive phenomenon of sacredness even limits the thoughts that are comfortable for an individual to have regarding the sacred object.

What is the sacred? What does it look like, and how does it behave? Jonathan Haidt, investigator and popularizer of moral foundations theory, gives the following hint about the sacred: “The fundamental rule of political analysis from the point of psychology is, follow the sacredness, and around it is a ring of motivated ignorance.” This epistemic feature— that sacredness protects itself by tabooing the wrong kinds of thought near its foundations—is exploited in the foundational legends of a culture, origin stories that are often sources of sacredness. Folklorist Linda Dégh might be regarded as an expert on the folkloric legend (as distinct from märchen, magic stories that English speakers would refer to as “fairy tales”). The main difference is that the legend is a personal story that invites genuine disbelief (think “urban legend”), whereas märchen are impersonal stories that are clearly not intended to be believed.

But sacred, foundational narratives are not ordinary legends, she says. In discussing the definition of the legend, Dégh says that there are some stories that she excludes from the label “legend”:

Arguing for the disputability factor as crucial, I excluded legend-like narratives that enforce belief and that deny the right of disbelief or doubt, narratives that express majority opinion and are safeguarded by moral taboos from negation and, what is more, from deviation.21

Dégh’s examples are “religious (Christian, hagiographic, or saint’s) legends,” and the “patriotic (heroic) legends dispensed through school education by governments, confirming citizens in civil religiosity.” Not only churches may form moral communities that function as religions, but ostensibly secular societies as well. We may not really question the harmfulness of tobacco or the benefits of breastfeeding and remain truly polite.

Sacred beliefs are those that are held by consensus within the moral community. It is useful for groups to share sacred beliefs—indeed, even outlandish beliefs—as these are costly signals of commitment to the group that enhance trust and cooperation within the religious community. Cognitive and social mechanisms reduce expression of ideas that threaten the sacred belief or object, and these social mechanisms have the function of a moral taboo to protect sacred truths from negation, or sacred purity from violation. As a result, people are indignant at the suggestion of trading off sacred values for ordinary values—and the more nakedly obvious the trade-off is made, the more indignant they will be.

Sacred beliefs are so powerful that outlandish beliefs are often maintained—even strengthened—in the face of strong disconfirmatory evidence. In their now-classic study,22 Festinger et al. give an account of a UFO cult whose leader predicted the destruction of the earth on December 20, 1954. The leader claimed that a spaceship would come before the destruction to rescue the faithful believers, but when the spaceship did not arrive as predicted and the world was not destroyed, the group faced a serious threat to its underlying sacred beliefs for which the members had sacrificed a great deal. Yet the group did not dissolve in shame. They were receptive to a new message received by their leader, to the effect that their faithfulness had spared the world from destruction. The group is reportedly still active today. The group-maintained sacred belief was so strong that even the most damaging possible evidence was not enough to undermine it.

So much for the UFO crazies. But it was only a couple of decades ago in the United States that it was widely believed that satanic cults were abusing and murdering vast numbers of children. The McMartin Preschool trial allowed prosecutors to spin a tale of the perfect sacredness violation: an evil conspiracy by entrusted adults to sexually abuse vulnerable children. As unprecedented numbers of women entered the workforce in the 1980s the expanded use of daycare increased guilt and uncertainty associated with leaving children under the supervision of unrelated caregivers, setting the stage for the perfect sacredness violation to become a moral panic. No convictions resulted from the McMartin Preschool trial, but over the course of the three-year trial the lives of the accused were irreparably damaged. Similar accusations would soon lead to the erroneous prosecution, conviction and imprisonment of many unfortunate scapegoats.23 The Arkansas teens known as the “West Memphis Three,” for example, were convicted of ritually murdering three children toward the end of the moral panic in 1994,24 despite the fact that no forensic evidence tied any of them to the crimes; they were released in 2011 after spending over eighteen years in prison.

The connection between sacredness and victimhood can be understood from such examples. Innocent children left in the care of strangers provided the most vulnerable possible victims, and better yet for memetic transmissibility, this victim status was up for grabs. Recovered memory therapists sought clients with the message that anyone might be a victim of satanic ritual abuse and not know it. The offer of status and attention for “recovering” memories of abuse found many takers. It is often the case that when a sacred belief assigns special status to victims of particular holiness, the number of these extra-holy victims grows.

Sacredness is most clearly revealed in its violation, especially in the modern world in which conflicting worldviews often collide. The violation of sacredness triggers the social mechanisms that protect the sacred object from attack.

The sacredness system may be viewed as having two components: first, the individual human capacity to perceive and respond to sacredness; and second, the cultural items that are held to be sacred. There is great variety in the nature of things held to be sacred, though these follow regular patterns, generally representing collective group interests. Fashions in sacredness travel quickly, as illustrated in the introductory examples. The human capacity to perceive sacredness—sacredness susceptibility—varies within human populations and likely between populations, though probably more in magnitude than in the nature of the underlying psychological processes.

The window into the workings of sacredness is especially wide in the modern world, in which members of different moral communities with conflicting sacrednesses frequently interact. In an established, insular community in which everyone understands the same sacredness and wishes to avoid giving offense (thus risking rejection from the community), sacredness violations are likely much rarer.

Sacred beliefs can only be maintained by the community, but they are stored in the minds and bodies of community members as part of their individual and group identities. To a believer in a particular sacredness, an attack on that sacredness is an attack on himself. Sacredness violations are perceived as aggressions, and produce similar physiological states of arousal; the poor person experiencing an attack on his sacred foundation has no choice whether to feel this psychological pain. Relying on a particular sacredness leaves us vulnerable to violations—and our responses to this violation protect the sacred object. We must choose our sacrednesses wisely; circling the totems of our community is an excellent strategy.

Thanks to the candor of Internet communications, we know something about the physiological effects of suffering a sacredness violation. When confronted with a threatening worldview, sufferers report a variety of physical symptoms, such as heart pounding, shaking, and vision changes; some think they will “black out” from rage. These symptoms line up well with a “fight or flight” arousal response to aggressive threats. Indeed, in this state, the victim of the sacredness violation wishes violence (and even a violent end) on the violator with disturbing frequency, even when the sacredness violation was not violent in nature.25

Sacredness violations threaten all four types of meaning detailed in Chapter 2. First, our sacred objects are frequently identical with our value bases or terminal values; the threat to the sacred is a threat to the foundation of all else. Second, sacredness violations may threaten the plausibility of fulfillment states, the (largely imaginary) future states of perfect happiness and justice that we are all supposed to be working toward and making it easier for each other to believe in. Third, sacredness violations that relate to identity and self-worth are particularly painful; the modern self carries a heavy burden of meaning, and even very mild and realistic reminders of one’s own ordinariness or mediocrity can be devastating. When one has attached a sacred meaning to an aspect of his identity, the threat to this sacred meaning is perceived the same as a threat to his physical person. Finally, sacredness violations threaten efficacy, making us feel powerless in the face of attack; it is common for individuals so threatened to attempt to form a coalition of sacredness violation victims with which to confront the violator.

It is important to understand that sacredness violations actually do subjectively hurt the person experiencing the violation, and that he has little or no control over this process. Empathy demands attention to sacredness, and sacredness is maintained and standardized within the community as much by the desire to avoid hurting others as by the desire to avoid being exiled from the group for insufficient piety. This process means that what is held sacred by people within a moral community will tend to converge on a consensus, even if they start out with a variety of notions of the sacred.

In sum, when a sacredness violation occurs the victim whose sacredness is threatened perceives an aggression and enters a state of fight-or-flight arousal. When the reaction is threatening enough the victim will seek to form a coalition condemning the sacredness violation. (Incidentally, this has the effect of spreading the offending violation to more eyes and ears; some publicity strategies specialize in triggering a sacredness reaction in the hope that it will lead to sharing as part of coalition building.) Finally, if a powerful enough coalition forms, the violator will be sanctioned, either with threats or actual harm, up to and including the loss of his social position.