| The Story of Silver | Source |

|

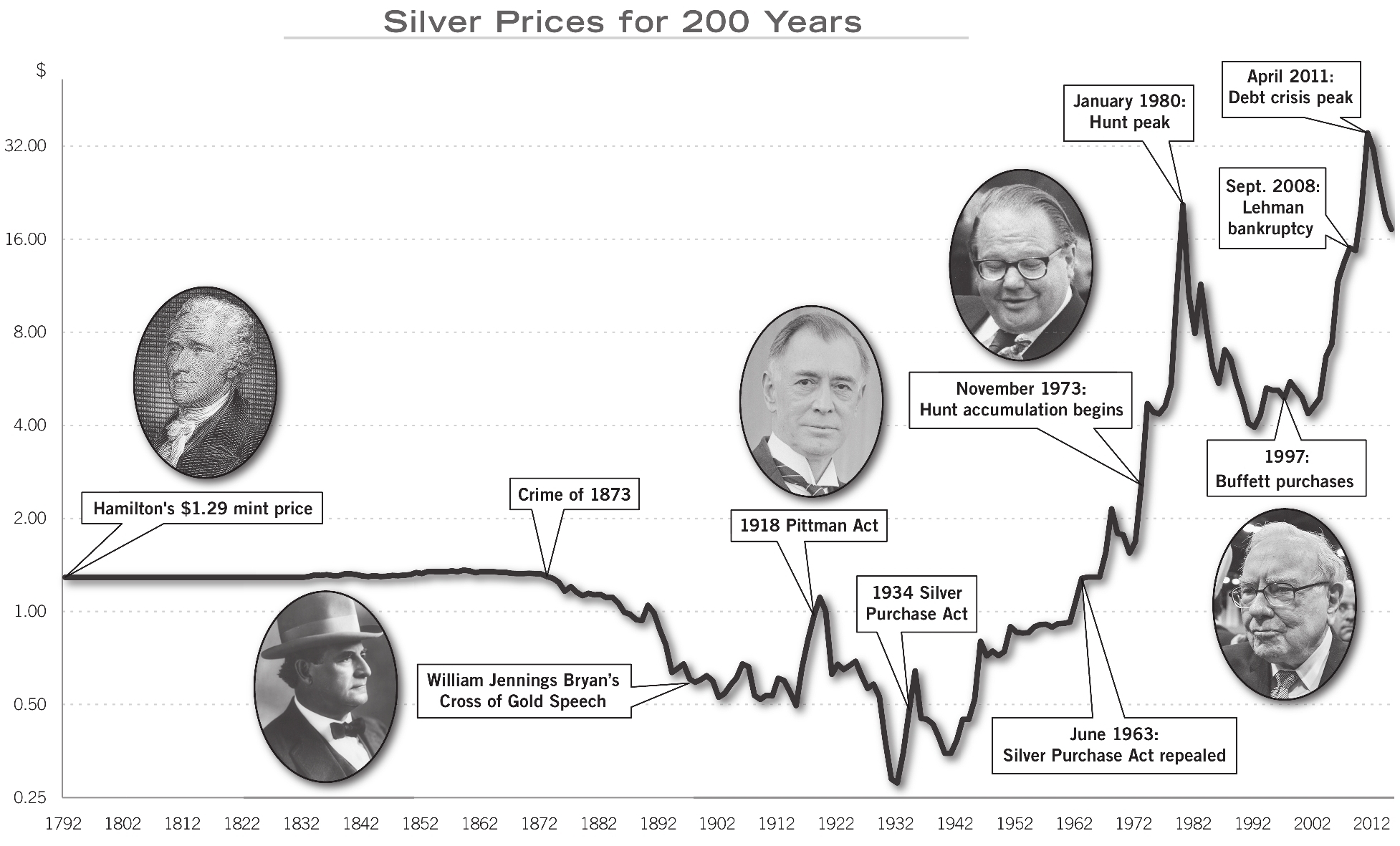

This is the story of silver’s transformation from soft money during the nineteenth century to hard asset today, and how manipulations of the white metal by American president Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1930s and by the richest man in the world, Texas oil baron Nelson Bunker Hunt, during the 1970s altered the course of American and world history. FDR pumped up the price of silver to help jump start the U.S. economy during the Great Depression, but this move weakened China, which was then on the silver standard, and facilitated Japan’s rise to power before World War II. Bunker Hunt went on a silver-buying spree during the 1970s to protect himself against inflation and triggered a financial crisis that left him bankrupt.

Silver has been the preferred shelter against government defaults, political instability, and inflation for most people in the world because it is cheaper than gold. The white metal has been the place to hide when conventional investments sour, but it has also seduced sophisticated investors throughout the ages like a siren. This book explains how powerful figures, up to and including Warren Buffett, have come under silver’s thrall, and how its history guides economic and political decisions in the twenty-first century.

| Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 |

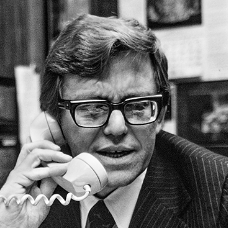

Introduction: Obsession Hamilton’s Design Solving the Crime of 1873 Free Silver Seeds of Roosevelt’s Manipulation FDR Promotes Silver Silver Subsidy China and America Collide Bombshell in Shanghai Silver Lining Costly Victory JFK’s Double Cross LBJ Nails the Coffin Shut Psychiatrist’s Meltdown Battle Lines Nelson Bunker Hunt Heavyweight Fight Saudi Connection Silver Soars Collapse The Trial Buffett’s Manipulation? Message from Omaha The Past Informs the Future Bibliography Endnotes |

xi 1 3 6 8 10 12 14 18 25 28 30 34 38 43 44 49 52 55 61 68 74 77 81 82 88 |

A lover of silver will never be satisfied with silver.

—Ecclesiastes 5

To

Danny

You left us too soon

I did not know Nelson Bunker Hunt, whose death in 2014 spawned this book project, but many who knew him well shared their insights and recollections. I could not have written the story of silver without them. Phil Geraci of the Kay Scholer law firm that represented the Hunt brothers during their silver manipulation trial was a young lawyer back then and provided key personal observations from his six-month interaction with the Hunts. His assistant Patricia Apuzzo made it easy to use the related material.

Henry Jarecki, whose business dealings with the Hunts while chairman of Mocatta Metals Corporation lasted more than a decade, gave me access to his unpublished manuscript that offered details unavailable elsewhere. His assistant Emily Goodnight made the process enjoyable and productive. Professor Jeffrey Williams served as an expert witness for the Hunts at their 1988 trial and provided copies of plaintiff and defendant expert reports that had been stored in his garage since then. I also relied on his excellent book on the economic testimony at the trial.

But this book is more than just about the Hunts. It is the story of silver, so at the beginning I spent a day with silversmith Geoffrey Blake at Old Newbury Crafters in Amesbury, Massachusetts, watching him mold the white metal into sterling silver flatware with the same tools and techniques that Paul Revere might have used.

The ancient craft practiced in Blake’s dusty basement workshop contrasted with the modern spectrograph used by Don and Angelo Palmieri in their Gem Certification & Assurance Lab to determine whether sterling silver jewelry contains the required 92.5% pure silver. But some things do not change. I watched Albert Robert (Irina and Gabriel’s cousin) of the New York Gold Refining Company turn a silver coin into molten metal by heating it in a blackened crucible over an open flame as in ancient times.

My research work benefited from the cheerful effort of many individuals. I owe Carol Arnold-Hamilton, Alicia Estes, and Robert Platt, librarians at NYU’s Bobst, for recovering source material that challenged Google’s algorithms. Jack Shim, an outstanding PhD student at NYU Stern, and Omer Morashti, a great Stern MBA, analyzed the data with surgical skill. Bob Oppenheimer shared firsthand observations of the silver ring at the Commodity Exchange (Comex). Bernard Septimus, my friend for as long as I can remember, applied his biblical expertise to keep my references consistent with modern scholarship. Seth Ditchik and Bruce Tuchman read an early draft and molded the framework of the story for the better. Dick Sylla, Ken Garbade, and Paul Wachtel read the entire manuscript as if it were their own and scrubbed the fuzzy logic from the final product. Peter Dougherty, my editor at Princeton University Press, offered sage advice and gentle encouragement throughout the process. His e-mails at 5 a.m. were just the tip of the iceberg. My wife, Lillian, let me work on the book whenever I wasn’t playing golf, read every word, and excised most (but certainly not all) of the annoying metaphors. And I apologize to my children and grandchildren for not calling the book “Silber on Silver,” a unanimous recommendation at our family gatherings that fell to the cutting room floor like so many other gems.

No one needs to read the notes appearing at the end of the book, but they are there to expand on historical details and to provide technical information. The notes contain citations to newspapers, periodicals, academic articles, and books to support specific opinions and quotations appearing in the text. Statistical tests and a precise explanation of silver price data also appear in the notes. Silver prices usually refer to the price of physical silver in the form of bullion bars. These are sometimes called cash prices to distinguish them from prices in the futures market that become important in the second half of the book. The silver price data come from a variety of sources:

- annual data during the nineteenth century come from the Annual Report of the Director of the Mint, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1936;

- daily data on silver prices during the 1930s were hand-collected from the Wall Street Journal, which published cash market quotations by bullion dealer Handy & Harman;

- daily data on cash prices since 1947 and futures prices since 1963 were purchased from the Commodity Research Bureau (CRB), an independent data distributor that was a division of Knight-Ridder Financial Publishing and is now a division of Barchart.com, Inc., a Chicago-based vendor of financial data; and finally,

- daily data on the London silver fix since 1968 come from the London Bullion Market Association as published by Quandl, an internet provider of economic and financial data.

| Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Figure 6 Figure 7 Figure 8 Figure 9 Figure 10 Figure 11 Figure 12 Figure 13 Figure 14 Figure 15 Figure 16 Figure 17 Figure 18 Figure 19 Figure 20 Figure 21 |

National Photo Company Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-npcc-24200 Everett Historical / Shutterstock.com Brady-Handy Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-04797 Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-22703 Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-86702 Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images nsf / Alamy Stock Photo Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History (top) Photograph by Dimitri Karetnikov; (bottom) United States Mint John Marmaras Photography AP Photo/Charles Wenzelberg Central Press / Stringer / Hulton Archive / Getty Images doomu / Shutterstock.com Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images Bettmann / Contributor / Getty Images Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. www.cngcoins.com Bloomberg / Contributor / Getty Images United States Mint |

The outline of this book when I started five years ago differs considerably from the final product. History surprised me with events and personalities that changed my thoughts and perceptions. I have shared those stories with you throughout this book and hope they are as pleasurable, instructive, and exciting for you as they were for me.

|

William L. Silber is the Marcus Nadler Professor of Economics and Finance at the Stern School of Business, New York University. He received NYU’s Distinguished Teaching Medal in 1999 and was voted Professor of the Year by Stern MBA students in 1990, 1997, and 2018. He received his PhD in economics from Princeton University and has written about monetary economics and financial history, including seven books, most recently, Volcker: The Triumph of Persistence, which chronicles the career of former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker. The Volcker biography won the China Business News Financial Book of the Year in 2013, was a finalist in the Goldman Sachs / Financial Times Business Book of the Year in 2012, and was named “One of the Best Business Books of 2012” by Bloomberg Businessweek. His first book, Money, coauthored with Lawrence Ritter, made a serious topic fun to read.

William L. Siber at Wikipedia

By the Same Author

Volcker: The Triumph of Persistence

When Washington Shut Down Wall Street: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914 and the Origins of America’s Monetary Supremacy

Financial Options: From Theory to Practice (coauthor)

Principles of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets (coauthor)

Financial Innovation (editor)

Money (coauthor)

Portfolio Behavior of Financial Institutions

(IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER)

Lamar Hunt, the thirty-four-year-old owner of the Kansas City Chiefs football team, negotiated the merger of the upstart American Football League with the older and well-established National Football League in 1966, creating the most successful sports enterprise in America. Hunt also invented the name Super Bowl, originally the championship game between the two leagues, and now the most popular single sporting event in the country. He explained the origin of his inspiration: “My daughter, Sharron, and my son, Lamar Jr., had a children’s toy called a Super Ball, and I probably interchanged the phonetics of ‘bowl’ and ‘ball.’”1

The first Super Bowl was played in January 1967 and pitted Hunt’s Kansas City Chiefs against Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers. The Packers walloped the Chiefs 35–10 and were awarded the Super Bowl trophy, a seven-pound sterling silver football made by Tiffany & Company. Winners of the annual Super Bowl since then have received an identical creation, now called the Vince Lombardi Trophy, with the winning team’s name engraved on the pedestal by Tiffany craftsmen.

Lamar was proud of his franchise, especially after his Chiefs won the Super Bowl in January 1970, but he had no way of knowing that ten years later the trophy itself would be worth twenty-five times its original value, and not just for sentimental reasons. In January 1980 the price of silver had jumped to $50 an ounce, a modern record that still stands, and Lamar, together with his older brothers Nelson Bunker Hunt and Herbert Hunt, would be accused of rigging the price of the white metal in the boldest commodities market manipulation of the twentieth century.2

Lamar, Nelson Bunker, and Herbert were sons of H.L. Hunt, a poker-playing oil tycoon whose right-wing political outlook equated New York’s liberal Republican governor, Nelson Rockefeller, with Cuba’s Fidel Castro. The family patriarch taught his children to distrust government, especially its paper currency, and to invest in real things, such as oil, land, and precious metals. He established trusts for his children, including shares in the family’s billion-dollar crown jewel, the Placid Oil Company, which served as a funding source for their business ventures. The tall and trim Lamar, as mild mannered as an accountant, concentrated on football during the 1960s, while his outspoken older brother Bunker, as Nelson was called, concentrated on racehorses and oil fields. Bunker was a pear-shaped 250-pounder who enjoyed the limelight that came with being the family spokesman. A speculator like his father, Bunker may have been the richest man in the world after oil was discovered in Libya, where he owned the drilling rights. Bunker had made his deal with Libya’s King Idris, but before he could enjoy all the fruits of his speculations, insurgents led by Muammar Qaddafi overthrew the monarchy in 1969 and soon after nationalized the oil fields. Bunker was still a billionaire, when a billion dollars was real money, but the incident increased his distrust of government.

Bunker affirmed his conservative credentials by joining the John Birch Society, the Tea Party of its day, and began investing in silver because he feared government spending would produce inflation and erode the value of the U.S. dollar.3 He also thought he could store his cache of the precious metal on his two-thousand-acre Circle T ranch near Dallas without worrying about Qaddafi. But his speculation quickly turned into an obsession, and even Texas was not big enough for his holdings. Between 1973 and 1979 he led his brothers in accumulating almost 200 million ounces of the white metal, stored in New York, London, Switzerland, and other locations that may not have been publicly disclosed. The Hunt silver was worth about $2 billion in September 1979. Four months later, when silver hit $50 an ounce, it came to nearly $10 billion.

Then it all disappeared. Within a year Bunker Hunt was forced to pledge his shares in Placid Oil as collateral for a billion-dollar loan to avoid bankruptcy. He had personally borrowed heavily to buy silver and the value of his leveraged holdings collapsed when prices fell back to $10 an ounce, a drop that rivaled the decline in the Dow Jones stock index during the Great Depression. He and his brothers were then found liable for conspiring with Saudi Arabian sheikhs to corner the silver market during their speculative binge. Bunker Hunt declared personal bankruptcy after the trial and lost prized possessions to his creditors, including fifteen ancient Greek vases and a collection of silver coins dating from the Roman Empire.4 When an older sister asked what had happened, he answered, “I was just trying to make some money.”5

The Hunts were not the first nor the last to be seduced by the white metal. In 1997 Warren Buffett, perhaps the most successful investor of the past fifty years, bought more than 100 million ounces, almost as much as the Hunts, and drove the price of silver to a ten-year peak. In 1933 Franklin Delano Roosevelt raised the price for silver at the U.S. Treasury to mollify senators from western mining states while ignoring the help it gave Japan in subjugating China. And in 1918 Senator Key Pittman of Nevada subsidized his home state constituents by sponsoring legislation to sell silver to India during the Great War. But the white metal has been more than just a vehicle for personal advancement to Americans; it has been part of the country’s monetary system since the founding of the Republic and is woven into the fabric of history like the stars and stripes.

1. Lamar Hunt, a Force in Football, Dies at 74, New York Times, December 15, 2006, p. C12.

2. The related designation “boldest futures manipulation of the twentieth century” is from Burton Malkiel, A Random Walk Down Wall Street, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 2015), p. 417. The peak price was an intraday high of $50.36 for spot silver (i.e., for the January futures contract) recorded on January 18, 1980, on New York's Commodity Exchange (see New York Times, January 19, 1980, p. 36). An intraday high of $50.50 was recorded on the Chicago Board of Trade.

3. For Bunker's association with the John Birch Society, see Stephen Fay, Beyond Greed (New York: Viking Press, 1982), pp. 18-19.

4. Bankrupt Hunt Brothers Bid Adieu to Art Collections Worth Billions, Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1990, p. C1.

5. Nelson Bunker Hunt, 88, Oil Tycoon with a Texas Size Presence, Dies, New York Times, October 22, 2014, p. A24.

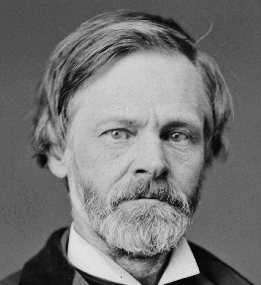

Perhaps the most famous speech in American electoral politics, Nebraska Congressman William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” sermon at the 1896 Democratic convention, was all about silver. Bryan became the party’s nominee for president after delivering an address that would make a modern televangelist blush: “I come to speak to you in defense of a cause as holy as the cause of liberty—the cause of humanity … that all believers in free coinage of silver in the Democratic Party should organize and take charge of and control the policy of the Democratic Party … We do not come as aggressors. Our war is not a war of conquest. We are fighting in the defense of our homes, our families, and posterity.”6 Bryan’s cause, the resurrection of silver as a monetary metal, aimed to rectify the injustice perpetrated by the Crime of 1873, which discontinued the coinage of silver dollars that Congress authorized in 1792 and established gold as king of American finance. The demonetization of silver sparked a great deflation in the United States during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, with declining agricultural prices provoking resentment among midwestern farmers against East Coast bankers. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which has entertained millions since it was published in 1900, is an allegory of the contemporary class warfare.

The abundance of silver in America during the 1870s made it the metal of the people, synonymous with cheap money compared with the more restrictive supply of currency under the gold standard. Bryan viewed remonetizing the white metal as a way to promote inflation to reduce the burden of mortgages owed by farmers to the banks. A century later, during the 1970s, the Hunts invested in silver as a bulwark against inflation, a rock-hard asset to protect their fortune against the spendthrift ways of the government. This is the story of silver’s transformation from soft money during the nineteenth century to hard asset today, and how manipulations of the white metal have altered the modern world; but to understand the attraction of silver to politicians and its vulnerability to speculators and schemers requires historical perspective.

Silver is the preferred protection against government defaults, political instability, and inflation for people in most countries, a place to hide when conventional investments sour. In the three years following the financial crisis of 2008, when banks teetered on the brink of insolvency and the government debts of Italy, Ireland, and Greece resembled junk bonds, anxious investors drove up the price of silver by almost 400%, an increase greater than ten years of Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway stock.7 But the precious metal is more than just another safe-haven investment. For centuries it has been hammered by silversmiths into serving platters, candlesticks, and wine goblets for the upper classes. Families display these heirlooms with pride in their dining room cupboards to highlight an affluent past, but during bad times they are quietly sold for cash.

Silver has also been the monetary standard of almost every country in the world, including China and Saudi Arabia in the twentieth century, Great Britain in the seventeenth, and Biblical Egypt. Britain dominated world commerce with the gold standard during the nineteenth century, but its currency is still called “the pound sterling,” a paradoxical reference to sterling silver as the standard. The word “sterling” means that a coin, candelabra, or Super Bowl trophy contains 92.5% pure silver, with the remaining 7.5% usually consisting of copper for strength. A mixture of nitric acid and potassium dichromate produces a different color on a sample scraping of “fine” silver, which is 99.9% pure, compared with sterling, and there is little to dispute once the sample has been assayed (tested) professionally.8 Governments guarantee the purity and weight of coins minted from precious metals to make the currency generally accepted without further testing, and silversmiths engrave 925 or the word sterling on their work to certify its quality. Queen Elizabeth I, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, ascended the throne in 1558 and two years later made the metal backing the British currency one pound of sterling silver.9 This so-called “ancient right standard of England” originated in the eleventh century under William the Conqueror, but had been debased by the gluttonous Henry before Elizabeth’s rescue.10 The sterling reference stuck despite Britain’s switch to gold and survives today even though the silver content of the pound is long gone.

The clash between ornamental demands by silversmiths and government coinage often had surprising consequences. Louis XIV, the absolute monarch of France for seventy years until his death in 1715, turned the magnificent silver furniture and tableware in the Palace of Versailles into bullion bars for minting by his Treasury.11 Silver dishes with matching place settings became common currency. The remaining French nobility had little choice but to follow the king’s example—Louis is famous for the proclamation, “L’État, c’est moi” (I am the state). The results were fiscal credibility in France and a scarcity value in the surviving silver antiques.

6. Speech Concluding the Debate on the Chicago Platform, in William Jennings Bryan, The First Battle: A Story of the Campaign of 1896 (Chicago: W.B. Conkey Company, 1896), pp. 199-200.

7. The cash price of silver on September 12, 2008, the Friday before the investment bank Lehman Brothers announced its bankruptcy, was $10.87 per ounce. Three years later on September 12, 2011, during the height of the European sovereign debt crisis, silver was $40.26 per ounce, for an increase of 370% over the three year period. Berkshire Hathaway closed at $103,800 on September 12, 2011, compared with a price of $68,000 on September 10, 2001, an increase of less than 100%. Note: As described in “From the Author” at the beginning of this book, cash prices after the 1930s come from the Commodity Research Bureau (CRB) database (the SIY series), unless noted otherwise. Berkshire Hathaway stock prices are from Yahoo! Finance.

8. I witnessed this test conducted by Donald and Angelo Palmieri of the Gem Certification & Assurance Lab (GCAL), 580 Fifth Avenue, New York City, although it was not easy for me to distinguish the colors. They also confirmed this test with a more modern X ray fluorescence technique. For a discussion of assaying by fire from ancient times to the present see J.S. Forbes, Hallmark: A History of the London Assay Office (London: Unicorn Press, 1999), pp. 20-24. Also see

http://www.sciencecompany.com/HowtoTestGoldSilverandOther PreciousMetals.aspx

9. See A.E. Feavearyear, The Pound Sterling: A History of English Money (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931), chap. 4; and Seymour Wyler, The Book of Old Silver (New York: Crown, 1937), p. 7. According to Thomas Sargent and Francois Velde, The Big Problem of Small Change (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2002), pp. 82-83, One pound represented different amounts of gold and silver at different times,” which may be true, but both Wyler and Feavearyear confirm that Elizabeth promulgated the sterling standard of “11 ounces, 2dwt.” There are 20 pennyweights (dwt) in a troy ounce so sterling meant 11.1 troy ounces, which is .925 of a troy pound (= 12 troy ounces).

10. Feavearyear, Pound Sterling, p. 8.

11. Daniëlle O. Kisluk-Grosheide and Jeffrey Munge, The Wrightsman Galleries for French Decorative Arts (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010), p. 106.

Governments no longer coin silver as currency but rising industrial demands compete with silversmiths for the available supply of the white metal. Photographic film produced by the camera company Eastman Kodak usually consumed more silver in a year than the jewelry industry.12 Now that digital cameras have made photographic film obsolete (driving Kodak into bankruptcy in 2012), the electronics industry dominates commercial uses. Silver, called a noble metal, along with gold and platinum, because it resists corrosion, is the best conductor of electricity and is used in circuit breakers, switches, fuses, and other electrical components. Modern technology has also exploited silver’s antibacterial properties. In 2006 the giant Korean manufacturer Samsung introduced a washing machine that releases silver ions in the wash cycle to help sanitize the laundry.13 Specialty retailer Sharper Image advertised a plastic food container infused with silver nanoparticles to keep food fresher, which received positive feedback on Amazon from users.14 And in 2017 Colgate University in central New York state sprayed its locker rooms with a decontaminating fog of hydrogen peroxide and silver to combat the deadly MRSA staph infection.15 The white metal’s industrial demand now exceeds its combined use in jewelry, bullion bars, and commemorative coins.16

Silver attracts manipulators because occasional bursts of speculative fever clash with rising commercial use, especially when citizens fear political unrest. The resulting price gyrations allow conspirators to promote higher prices with relatively little effort while also camouflaging their manipulation. On November 4, 1979, during the height of the alleged Hunt conspiracy to corner the silver market, Iranian students invaded the U.S. embassy and took American citizens hostage.17 The ensuing political crisis contributed to the tripling of silver prices during the next three months, masking the footprints of the manipulators.18

Gold is the primary store of value for those who mistrust the government, but silver remains the refuge of choice for most people because it is cheaper and more accessible. A standard 100-ounce bar of silver, about the size of three Hershey bars stacked on top of each other, costs about $1,700 today compared with a price of $130,000 for a 100-ounce gold bar. The relatively small dollar size of the silver market makes the white metal more volatile than the yellow, where a million-dollar order from anxious buyers and sellers makes a bigger impact.19 Silver led the jump in precious metals after the 2008 financial crisis with nearly a 400% increase compared with almost 250% for gold.20

For most of recorded history paper currency was acceptable in everyday transactions because governments promised to exchange those pieces of paper for gold or silver, which gave money intrinsic value. U.S. citizens could exchange dollars for gold at the rate of $20.67 per ounce at the U.S. Treasury until 1933, and foreign governments could do the same at $35.00 per ounce between 1934 and 1971. President Nixon suspended the Treasury’s gold obligations on August 15, 1971, ending the last connection between the dollar and precious metals.

All countries now issue fiat currency, paper money backed only by the creditworthiness of the government. The verdict remains uncertain on this relatively new worldwide experiment in pure paper currency because governments have often abused their right to print money, destroying its value, as in the 1920s hyperinflation in Germany.21 Those concerned that the experiment will fail, such as the Hunts in the 1970s and the Tea Party today, seek refuge in the ageless storehouses of gold or silver. The great English economist David Ricardo, who learned a lot about money as a successful speculator, wrote almost two hundred years ago, “Experience, however, shows that neither a State nor a Bank ever have had the unrestricted power of issuing paper money, without abusing that power.”22 Ricardo recommended that “the issue of paper money ought to be under some check and control; and none seems so proper for that purpose as that of subjecting the issuers of paper money to the obligation of paying their notes, either in gold [or silver] coin or bullion.”23 Anchoring currencies to precious metals promoted price stability but caused controversy as well.

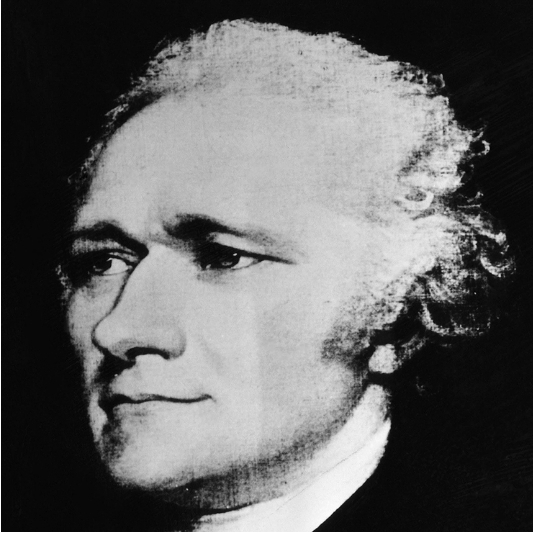

The United States, at the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, established the silver dollar alongside gold in 1792 as America’s currency. The two metals vied for public attention under this bimetallic standard until Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1873, eliminating the official status of silver and making gold the sole backing of America’s money.24 The scarcity of the yellow metal caused widespread price deflation over the next twenty-five years, and the reduced government demand for silver contributed to its decline in value of more than 50%.25 The subsequent outcry in western mining states for Congress “to do something for silver” made headlines throughout the country.26 William Jennings Bryan rode a silver train of resentment to the 1896 Democratic nomination for the presidency that ended in his defeat by William McKinley. Bryan ran twice more for the White House and lost, but none of those setbacks muffled the agitation for silver, which continued well into the twentieth century.

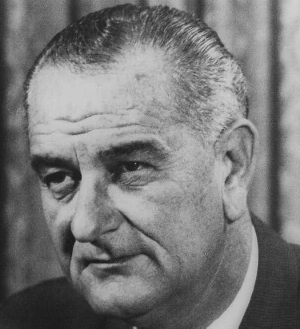

During the Great Depression, after the price of silver hit a record low of 24¢ an ounce, Democratic Senator Key Pittman of Nevada, the powerful chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, urged President Roosevelt to restore the white metal’s full monetary status.27 In exchange, Pittman promised the support of fourteen senators from western mining states for Roosevelt’s controversial New Deal legislation. FDR responded with a series of purchase programs for silver, beginning with an executive order on December 21, 1933, directing the U.S. Treasury to buy the domestically produced metal at 64.5¢ an ounce, a premium of 50% above the free market price of 43¢.28 The subsidy and the doubling of silver prices during Roosevelt’s first administration gave “the silver miners and speculators much for which to be thankful,” according to contemporary financial observers.29 Senator Pittman agreed and described FDR’s benevolence as a “Christmas present.”30

Pittman made good on his promise. He delivered the “silver bloc” senators in support of FDR’s 1933 pump-priming legislation, helping to jump-start the domestic economy, but U.S. diplomacy suffered a major blow. The higher price paid by the Treasury attracted silver from the rest of the world, especially from China, whose currency was backed by the precious metal. Despite local laws restricting exports, speculators smuggled silver out of Shanghai to profit on world markets and ultimately forced China to abandon the silver standard when that country was most vulnerable.31 It was 1935 and China, led by American ally Chiang Kai-shek, faced an internal threat from Mao Tse-tung’s communist insurgents and an external threat from Imperial Japan. Roosevelt’s Treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau, worried that China’s insecure government, weak economy, and susceptibility to Japanese aggression made her especially vulnerable to the dislocations arising from American silver policy.32

Morgenthau was right to worry. Roosevelt’s pro-silver program to please western senators helped the Japanese military subjugate a weakened China and boosted Japan’s march towards World War II, demonstrating the danger of formulating domestic policy without considering international consequences. Was FDR’s price manipulation less criminal than Nelson Bunker Hunt’s? Reading this book will let you make an informed judgment.

12. William E. Brooks, “Silver,” in U.S. Department of the Interior & U.S. Geological Survey. Minerals Yearbook 2008, vol. 1, Metals and Minerals (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2010), p. 68.2, available at

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?d=msu.31293031621463;view=1up;seq=902

13. See Rhonda L. Rundle, “This War against Germs Has a Silver Lining,” Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2006, updated 12:01 a.m. “Now, silver is showing up as a bacteria- and odor-fighting material in a range of contemporary consumer products, from sports socks to washing machines.”

14. Ibid.

15. “Constantly Battling a Hidden Foe,” New York Times, October 8, 2017, p. SP1.

16. See World Silver Supply and Demand at https://www.silverinstitute.org/site/supply-demand/.

17. “Teheran Students Seize U.S. Embassy and Hold Hostages,” New York Times, November 5, 1979, p. A1.

18. The price of spot silver (i.e., for the November contract on the Commodity Exchange) closed at $16.08 on November 2, 1979 (the last trading day before the hostage taking) and reached a high of $50.36 on the Commodity Exchange on January 18, 1980 (see note 2).

19. One measure of the relative size of the gold and silver markets comes from futures markets. Data for the Commodity Exchange on December 31, 2014, show a total open interest (total number of contracts outstanding) for gold of 371,646 contracts and a total of 151,215 contracts for silver. These translate into dollar amounts as follows: Gold contracts are for 100 ounces and the cash price per ounce on December 31, 2014, was $1,184, for a total of $44 billion. Silver contracts are for 5,000 ounces at a cash price of $15.69 per ounce for a total value of $11.9 billion. These numbers are surely underestimates of the total value of gold and silver in the world, but the relative size of the two markets is confirmed by a completely different source and time period. U.S. Department of Commerce, The Minerals Yearbook: 1932–1933 Year 1931–32 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1933), p. 12, estimates the total value (at the much lower prevailing market prices) of all gold mined since 1493 as $22.9 billion versus $14.6 billion for the total value of silver.

20. Using the same three-year time period as in the earlier note for silver, the cash price for gold on September 12, 2008 was $766 per ounce and on September 12, 2011 it was $1,814 per ounce, for an increase of 237%.

21. See Milton Friedman, Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History (New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994), pp. 249–60.

22. David Ricardo, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (London: John Murray, 1817), pp. 506–7.

23. I have added silver in brackets in the quote based on a footnote in ibid., p. 503: “Whatever I say of gold coin is equally applicable to silver coin; but it is not necessary to mention both on every occasion.”

24. Among the most useful of the numerous studies of this incident are: Francis A. Walker, “The Free Coinage of Silver,” Journal of Political Economy 1, no. 2 (1893); Walter K. Nugent, Money and American Society; 1865–1889 (New York: Free Press, 1968), esp. chap. 12–13; Friedman, Money Mischief, chap. 3.

25. The highest price during this twenty five year period was $1.29375 in 1874 and the lowest price was $.5275 in 1897. See U.S. Mint, Annual Report of the Director of the Mint for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1936 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1936), p. 88.

26. See, for example, the reference in a speech by Representative Charles H. Grosvenor of Ohio on February 3, 1896, 54th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record and Appendix, 27, pt. 7, App. p. 83.

27. I collected daily quotes published by Handy & Harman from the Wall Street Journal during the 1930s, and the data show a low of 24.25¢ per ounce on December 29, 1932. According to Herbert M. Bratter, Silver Market Dictionary (New York: Commodity Exchange, 1933), p. 99, “The New York ‘official’ price is determined and issued daily, usually in the late forenoon, by Handy & Harman, and is based upon the market prices prevailing that day up to the time of such determination for nearby delivery in New York of spot silver in round amounts of 50,000 ounces.”

28. For a contemporary discussion, see James D. Paris, Monetary Policies in the United States: 1932–1938 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938), pp. 48–49.

29. Ibid., p. 42.

30. “Pittman, Silver Pact Author, Sees Export Trade Increase,” Washington Post, December 22, 1933, p. 8

31. For a description of Chinese silver exports see “Shanghai Silver Again Moves Out,” New York Times, September 12, 1934, p. 13 and “Lower Silver Price Seen Necessary to End Smuggling,” Wall Street Journal, p. 1. On abandoning silver, Milton Friedman argues, “If the United States had not driven up the U.S. dollar price of silver, China would have left the silver standard later—perhaps several years later—than it actually did and under better economic and political conditions,” in Friedman Money Mischief, pp. 177–78.

32. See John Morton Blum, From the Morgenthau Diaries , vol. 1, Years of Crisis, 1928–1938 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1959), p. 204.

Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018941299

ISBN 9780691175386

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Peter Dougherty and Jessica Yao

Production Editorial: Natalie Baan

Text and Jacket Design: Leslie Flis

Production: Jacqueline Poirier

Publicity: James Schneider

Jacket Credit: 1879 US silver dollar

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std Roman

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2