| The Cosmic Serpent DNA and The Origins of Knowledge |

| “Those who love wisdom must investigate many things.” – Heraclitus |

|

|

This adventure in science and imagination, which the Medical Tribune said might herald "a Copernican revolution for the life sciences," leads the reader through unexplored jungles and uncharted aspects of mind to the heart of knowledge.

In a first-person narrative of scientific discovery that opens new perspectives on biology, anthropology, and the limits of rationalism, The Cosmic Serpent reveals how startlingly different the world around us appears when we open our minds to it.

The Cosmic Serpent is doubly themed.

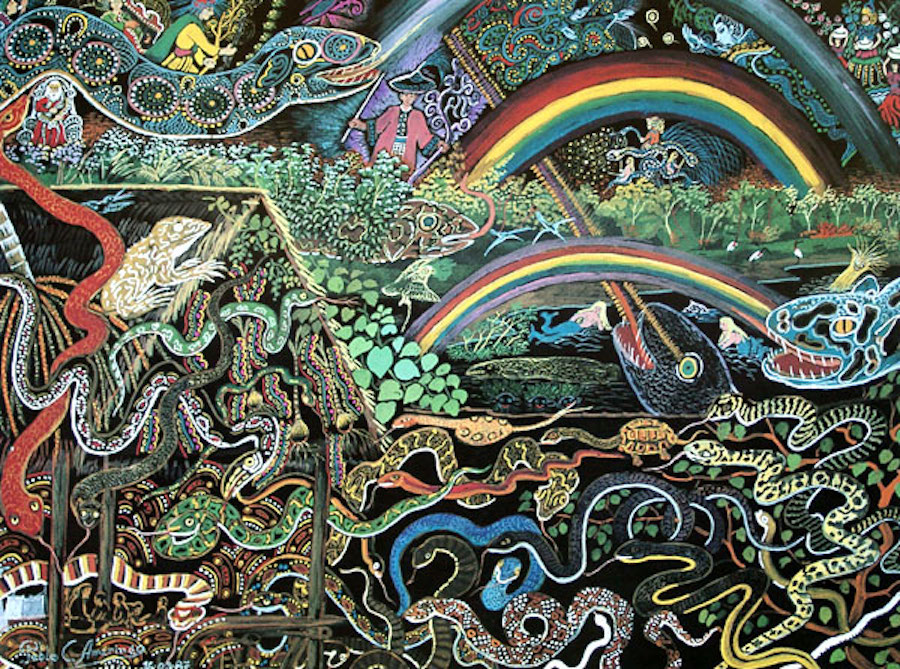

- One theme is that of the symbol of the creator serpent (or twin serpents) as the source of knowledge and of all life itself.

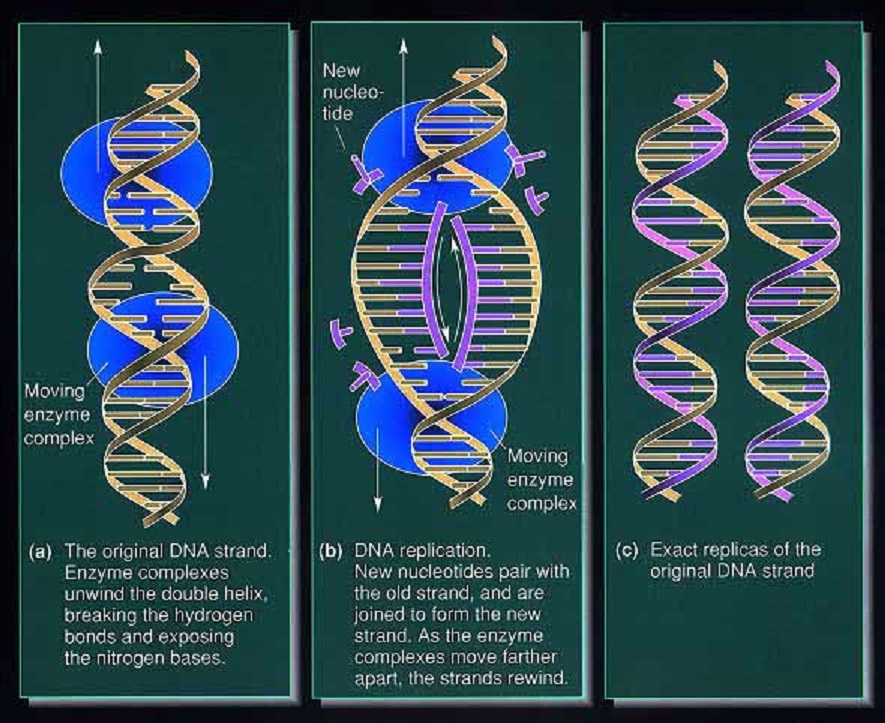

- The other theme is that of DNA which in our modern western world-view is the source of all life and all organic information.

- These two threads are wound about in a spiraling narrative like the double helix of the DNA molecule or the twin serpents found in the timeless myths of cultures the world over.

The Cosmic Serpent is a major breakthrough for not only the field of entheogens but for all science and perhaps religion too. Originally published in French as Serpent Cosmique, this book presents the journey of a western scientist who ventures past the primitive superstitions of modern anthropology and takes part in a millennia-long scientific research program of Amazonian shamanism; wherein he learns of their seers’ profound communication with other species via experiential access to DNA.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

|

Introduction Forest Television Anthropologists and Shamans The Mother of The Mother of Tobacco is A Snake Enigma in Rio Defocalizing Seeing Correspondences Myths and Molecules Through The Eyes of An Ant Receptors and Transmitters Biology's Blind Spot "What Took You So Long?" Bibliography | Index |

1 11 19 33 40 52 65 79 90 102 115

|

|

Jeremy Narby (born 1959 in Montreal, Canada) is an anthropologist and writer.

Narby grew up in Canada and Switzerland, studied history at the University of Canterbury, and received a doctorate in anthropology from Stanford University.

Narby spent several years living with the Ashaninca in the Peruvian Amazon cataloging indigenous uses of rainforest resources to help combat ecological destruction.

Narby has written three books, as well as sponsored an expedition to the rainforest for biologists and other scientists to examine indigenous knowledge systems and the utility of Ayahuasca in gaining knowledge.

Since 1989, Narby has been working as the Amazonian projects director for the Swiss NGO, Nouvelle Planète

|

“This is perhaps one of the most important things I learned during this investigation: We see what we believe, and not just the contrary; and to change what we see, it is sometimes necessary to change what we believe.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“When I started reading the literature of molecular biology, I was stunned by certain descriptions. Admittedly, I was on the lookout for anything unusual, as my investigation had led me to consider that DNA and its cellular machinery truly were an extremely sophisticated technology of cosmic origin. But as I pored over thousands of pages of biological texts, I discovered a world of science fiction that seemed to confirm my hypothesis. Proteins and enzymes were described as 'miniature robots,' ribosomes were 'molecular computers,' cells were 'factories,' DNA itself was a 'text,' a 'program,' a 'language,' or 'data.' One only had to do a literal reading of contemporary biology to reach shattering conclusions; yet most authors display a total lack of astonishment and seem to consider that life is merely 'a normal physiochemical phenomenon.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“Shamanism resembles an academic discipline (such as anthropology or molecular biology); with its practitioners, fundamental researchers, specialists, and schools of thought – it is a way of apprehending the world that evolves constantly. One thing is certain: Both indigenous and mestizo shamans consider people like the Shipibo-Conibo, the Tukano, the Kamsá, and the Huitoto as the equivalents to universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, and the Sorbonne; they are the highest reference in matters of knowledge. In this sense, ayahuasca-based shamanism is an essentially indigenous phenomenon. It belongs to the indigenous people of Western Amizonia, who hold the keys to a way of knowing that they have practiced without interruption for at least five thousand years. In comparison, the universities of the Western world are less than nine hundred years old.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“What if it were true that nature speaks in signs and that the secret to understanding its language consists in noticing similarities in shape or in form?” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent, DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“In truth, ayahuasca is the television of the forest.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“The rational approach start from the idea that everything is explainable and that mystery is in some sense the enemy. This means that it prefers pejorative, and even wrong, answers to admitting its own lack of understanding.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“An indigenous culture with sufficient territory, and bilingual and intercultural education, is in a better position to maintain and cultivate its mythology and shamanism. Conversely, the confiscation of their lands and imposition of foreign education, which turns their young people into amnesiacs, threatens the survival not only of these people, but of an entire way of knowing. It is as if one were burning down the oldest universities in the world and their libraries, one after another — thereby sacrificing the knowledge of the world's future generations.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“Wisdom requires not only the investigation of many things, but contemplation of the mystery.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“Nonetheless, gazing out the train window at a random sample of the Western world, I could not avoid noticing a kind of separation between human beings and all other species. We cut ourselves off by living in cement blocks, moving around in glass-and-metal bubbles, and spending a good part of our time watching other human beings on television. Outside, the pale light of an April sun was shining down on a suburb. I opened a newspaper and all I could find were pictures of human beings and articles about their activities. There was not a single article about another species.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“According to Eliade, the shamanic ladder is the earliest version of the idea of an axis of the world, which connects the different levels of the cosmos, and is found in numerous creation myths in the form of a tree.”

― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“During this investigation, I became familiar with certain limits of the rational gaze. It tends to fragment reality and to exclude complementarity and the association of contraries from it's field of vision...The rational approach starts from the idea that everything is explainable and that mystery is in some sense the enemy. This means that it prefers pejorative, and even wrong, answers to admitting its own lack of understanding.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

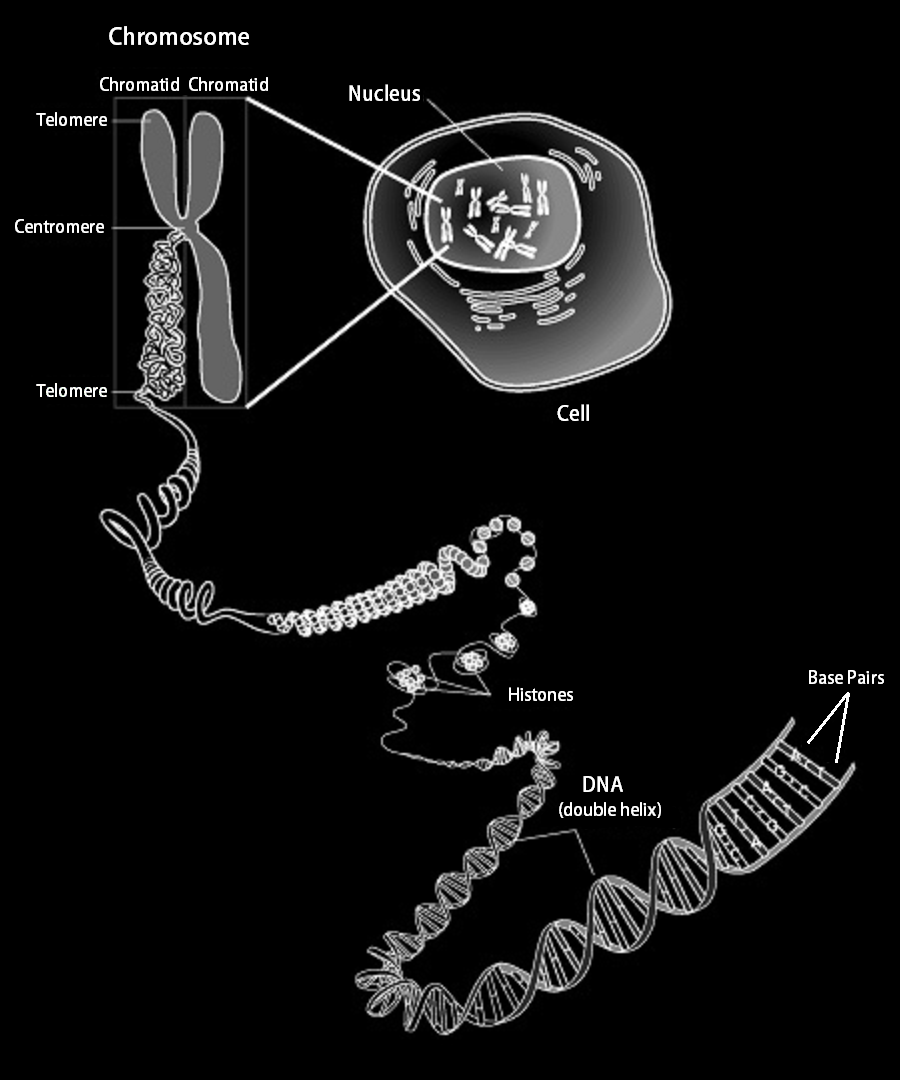

“If one stretches out the DNA contained in the nucleus of a human cell, one obtains a two-yard-long thread that is only ten atoms wide. This thread is a billion times longer than its own width. Relatively speaking, it is as if your little finger stretched from Paris to Los Angeles. ” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“This is an old problem: Knowledge calls for more knowledge,” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“One thing became clear as I thought back to my stay in Quirishari. Every time I had doubted one of my consultants' explanations, my understanding of the Ashaninca view of reality had seized up; conversely, on the rare occasions that I had managed to silence my doubts, my understanding of local reality had been enhanced — as if there were times when one had to believe in order to see, rather than the other way around.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“All the peoples in the world who talk of a cosmic serpent have been saying as much for millennia. He had not seen it because the rational gaze is forever focalized and can examine only one thing at a time. It separates things to understand them, including the truly complementary. It is the gaze of the specialist, who sees the fine grain of a necessarily restricted field of vision. ” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

“People’s bodies sometimes know things before people themselves do. In a controlled experiment, scientists asked people to draw cards from four decks, two of which were heavily skewed with penalties. Skin measurements showed that people contemplating the bad decks began sweating more profusely before they themselves could verbalize an intuition about which decks to avoid. Such research shows that emotions are a mix of brain states and body experiences, which include increased heart rate, hormonal activity, and input from the gut brain. It also shows that the body plays a role in the reasoning process. Having a gut feeling is not just a metaphor.” ― Jeremy Narby, Intelligence in Nature

“Arikawa is the scientist who discovered that butterflies have color vision, and that their tiny brains contain sophisticated visual systems. He also discovered that butterflies have eyes on their genitals.” ― Jeremy Narby, Intelligence in Nature

“We see what we believe, and not just the contrary; and to change what we see, it is sometimes necessary to change what we believe.” ― Jeremy Narby, The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge

From: goodreads

| |

Jeremy Narby, an anthropologist, discusses the intelligence of life, nature, ayahuasca and DNA communication.

- The interview also discusses how modern man has overlooked the inherent intelligence in nature.

- Narby discusses his experiences with the diplomat plant, Ayahuasca, and his work with the Ashaninca in the Peruvian Amazon.

- While there, Narby also cataloged indigenous uses of rainforest resources to help combat ecological destruction.

- Narby is the author of: The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge, Intelligence in Nature and Psychotropic Mind: The World According to Ayahuasca, Iboga, and Shamanism.

For more information on these interviews as well as more interviews: http://www.treemedia.com/#!11th-hour-...

Published on Feb 21, 2015 by TreeTV

In this mesmerizing talk, Jeremy Narby shares the findings from his groundbreaking book Intelligence in Nature.

- He describes his quest around the globe to chronicle how leading-edge scientists are studying intelligence in nature and how nature learns.

- He uncovers a universal thread of highly intelligent behavior within the natural world, and asks the question: What can humanity learn from nature's economy and knowingness?

- Weaving together issues of animal cognition, evolutionary biology and psychology, he challenges contemporary scientific concepts and reveals a much deeper view of the nature of intelligence and of our kinship with all life.

This presentation took place at the 2005 National Bioneers Conference and is part of the Ecological Design, Vol. 1 and Nature, Culture and Spirit, Vol. 1 Collections.

Since 1990, Bioneers has acted as a fertile hub of social and scientific innovators with practical and visionary solutions for the world's most pressing environmental and social challenges.

To experience talks like this, please join us at the Bioneers National Conference each October, and regional Bioneers Resilient Community Network gatherings held nationwide throughout the year.

For more information on Bioneers, please visit http://www.bioneers.org

Published on Dec 3, 2013 by Bioneers

The Cosmic Serpent reads more like a mystery novel than a standard anthropological study. I was particularly impressed by the honesty of the account, the cross-disciplinary nature of the argument, and the courage and reasoned conviction with which the author makes his argument.

Much is written lately about “indigenous knowledge,” especially in the field of traditional plant and medical knowledge. The vast number of indigenous societies in the Amazon region have received much fame recently in this area because of their knowledge and use of hallucinogenic materials. Modern pharmaceutical companies are especially interested in this knowledge, and many indigenous leaders and organizations have spoken about the need to protect their intellectual and cultural property rights, as well as to capture some of the economic benefits of such knowledge.

Jeremy Narby’s book places the discussion of indigenous knowledge in a deeper philosophical and cosmological framework, arguing for an epistemic correspondence between the knowledge of Amazonian shamans and modern biologists. The argument which Narby makes mines and reinterprets many of the sources in anthropology and biology on the subject. Some may argue that what Narby has found is mere chance or metaphoric correspondence, while others will appreciate the subtleties and truth value of the argument.

—Shelton H. Davis, Senior Sociologist World Bank

There is superstition in avoiding superstition, as Bacon once remarked, and I honor Jeremy Narby for finding his way through the numerous thickets that scientific reason has left behind in its attempts to turn plain truths of experience into the superstition it avoids. The Cosmic Serpent deals with the visionary experience that comes from taking ayahuasca, and Mr. Narby finds the claim that a plant means what it looks like is no superstition but a fact of experience: moreover, that the images of snakes and ladders that accompany the experience refer not only to the appearance of the ayahuasca vine but to that of the DNA spiral. To affirm this likeness he marshals the evidence of molecular biology and leaves the reader with the stunning intimation that the ayahuascan view of the world is none other than the scientific view seen from another perspective, that of selfhood rather than of no self at all.

Self is one topic that science is always superstitiously avoiding, and its biological origin has been called a veritable enigma. Narby’s book is a most intriguing and informative essay in restoring self to its proper place in the scheme of things, and makes the enigma look more like an open secret. It confirms my belief that the new paradigm we have come to expect will have the heart of the old one to give it life, and I see the book’s cosmic serpent as the herald of this wonderful moment.

—Francis Huxley, social anthropologist Author of The Way of the Sacred

Reviewed by Robert Forte, 7/24/2006

The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge is a major breakthrough for not only the field of entheogens but for all science and perhaps religion too. Originally published in French as Serpent Cosmique, this book presents the journey of a western scientist who ventures past the primitive superstitions of modern anthropology and takes part in a millennia-long scientific research program of Amazonian shamanism; wherein he learns of their seers’ profound communication with other species via experiential access to DNA.

In 1985 Jeremy Narby, a Stanford-trained anthropologist, was doing fieldwork for his dissertation in the Amazon Pichis Valley among the Ashaninca people. Inquiring how their extensive botanical-medicinal knowledge was derived he heard from a shaman that “one learns these things by drinking ayahuasca.” Narby thought the shaman was joking, and he had intended to leave that finding out of his report: “For me, in 1985, the ayahuasqueros’ world represented a gray area that was taboo for the research I was conducting.” But an “unexpected setback” caused Narby to move to the neighboring community of Cajonari where he was invited to partake of ayahuasca himself. Like a modern Adam he writes:

“Deep hallucinations submerged me. I suddenly found myself surrounded by two gigantic boa constrictors that seemed fifty feet long… I see a spectacular world of brilliant lights, and in the middle of these hazy thoughts, the snakes start talking to me without words. They explain to me that I am just a human being. I feel my mind crack, and in the fissures, I see the bottomless arrogance of my presuppositions. It is profoundly true that I am just a human being, and, most of the time, I have the impression of understanding everything, whereas here I find myself in a more powerful reality that I do not understand at all and that, in my arrogance, I did not even suspect existed. I feel like crying in view of the enormity of these revelations. Then it dawns on me that this self pity is a part of my arrogance. I feel so ashamed that I no longer dare feel ashamed. Nevertheless, I have to throw up again… I have never felt so completely humble as I did in that moment.”

From here Dr. Narby soars past the methodological limitations of modern anthropology and deciphers “the main enigma:” “the Ashaninca’s extensive botanical knowledge comes from plant induced hallucinations” via a sophisticated interdisciplinary study that includes direct personal experience of ancient shamanic mysteries, extensive comparative structural analysis of cross-cultural symbolism, and molecular biology. The result is the testable hypothesis “that the human mind can communicate in a defocalized consciousness with the global network of DNA based life.”

Deftly written, one hopes this book will cause quite a stir. It has already been reviewed in The New York Times. It is a major step toward western science’s reconsideration of the validity of shamanic states. The book’s neutral tone transcends the reactionary politics that infect entheogens within medical research, while avoiding tiresome theological questions. Here is pure exploratory science. Entheogens as heuristic.

Let us note that direct communication with DNA is not groundbreaking news in the psychedelic literature and it is remarkable that Narby, in his extensive scholarship, missed this. “To my knowledge,” he writes, “the only other mention of a link between hallucinogens and DNA is by Lamb (1985) who suggests in passing: ‘perhaps on some unknown unconscious level the genetic encoder DNA provides a bridge to biological memories of all living things…’.” Narby has completely missed Dr. Timothy Leary’s Info-Psychology wherein the subject is first presented:

“When the seventh circuit of the nervous system is activated, the signals from DNA become conscious. This experience is chaotic and confusing to the unprepared person — thousands of genetic memories flash by, the molecular family-picture-album of species consciousness and evolution. This experience provides glimpses and samples of the broad design of the multi-billion year old genetic panorama. …genetic engineers will use as their basic instrument their own brains, open to and conscious of neurogenetic signals. Only the DNA neuron link up can produce the immortality and symbiotic linkage with other species… The key to higher intelligence is direct DNA-RNA neural communication among species.”

And although the ayahuasca art of Pablo Amaringo is a frequent guide in Narby’s proof, he misses where Jonathan Ott presents Amaringo’s painting of the double helix of DNA on the cover of Pharmacotheon:

“The serpentine phantasmagoria of the visionary realm is dominated by the universal archetype of the Tree of Life… as well as the universal chemical liana of life on this planet — the double helix of DNA. The magical phlegm, azure essence of logos, the magical song or icaro of the yachaj made manifest, flows forth… like the serpents of creation from the woman’s womb; like the spermatozoa, human serpents of fecundity rising.”

Narby’s efforts expand and clarify Leary’s assertions and Ott’s poetic insight in such a way that should reach many skeptical readers outside the entheogen community. The example has been set for how entheogenic visions can elucidate other mysteries of creation: the appearance of matter, the incarnation of the soul, the destiny of our planet…

Sewn-and-glued hardcover, 257 pp; 2 page index, 5 page bibliographic index; 23 page bibliography, plus 58 pages of notes. This book is also available in paperback.

[Robert Forte is the editor of Entheogens and the Future of Religion and Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In.]

Originally Published In : The Entheogen Review, 1998

Reviewed by Rendi Case, 3/13/2007

The Cosmic Serpent is doubly themed. One theme is that of the symbol of the creator serpent (or twin serpents) as the source of knowledge and of all life itself. The other theme is that of DNA which in our modern western world-view is the source of all life and all organic information. These two threads are wound about in a spiraling narrative like the double helix of the DNA molecule or the twin serpents found in the timeless myths of cultures the world over.

The myths involving the serpent or twin serpents as the source of life and knowledge emerge from the ancient past with their tails hidden in the mists of prehistory. At the head of modern knowledge we have molecular biology and genetics; the study of that most serpentine of molecules – DNA. Like the Ouroboros, the cosmic snake of time and eternity that encircles the world swallowing its tail in a symbol of both unity and infinity, this book is an attempt to merge this cutting edge of scientific knowledge with the ancient source of wisdom steeped deeply in the shadows of our past.

The author, Jeremy Narby, holds a PhD in anthropology from Stanford University. In 1985 he began his fieldwork of two years in the Peruvian Amazon to earn his doctorate in anthropology. He wanted to show the Western world that the indigenous people of the Amazon basin knew best how to use their own land because international “development” agencies typically assert that indigenous people do not know how to use their own land “rationally” and use this rationalization to justify the “confiscation” (theft) of these people’s lands to use and exploit for their own greed and in the process destroy crucial ecosystems forever. Narby’s agenda was to establish protection of the territories of these Amazonian people by demonstrating that only they know how to best use their own land because they had intimate, sophisticated and pragmatic knowledge of their land. To appeal to Western civilization for support of his efforts, Narby had to emphasize the practical nature of these people’s knowledge of their land.

However, it was inevitable that in the course of his study with these people Narby would come up against the enigma of ayahuasca, the plant-based entheogenic brew par excellence of the Western Amazon rain forest. Commonly, the various ayahuasca using people of the Amazon tell us that they gain their knowledge of the many properties and uses of their local plants by consulting ayahuasca. In the visionary state induced by this brew, they are told many practical things; which plants to combine and use as a tranquilizer in which to dip their hunting darts, which plants to use to cure a given disease and how to use them, what plant to use to treat poisonous snake bites and so on. Narby felt that he had to avoid mentioning the fundamentally irrational origins of these people’s pragmatic knowledge because it would undermine his basic assertion that these people were perfectly rational and practical people.

As Narby points out, these people are very practical. But from our modern materialist perspectives, the source of their pharmacological knowledge is not at all rational because this knowledge is derived from what we would call hallucinations.

The modern Western view would deny that hallucinations could provide reliable and practical information, but if the knowledge these people gain from ayahuasca is merely delusional then how is it that this knowledge is so practical? Why does it work? If pharmaceutical companies make millions from the pharmacological knowledge gained from these people can we really dismiss their botanical knowledge as irrational or superstitious? Yet lawmakers in Europe and the United States assure us that ayahuasca is a dangerous drug with no medical or spiritual value.

While conducting his fieldwork, Narby stayed with the Ashaninca and Quirishari people of the Peruvian Amazon. When he questioned them about how they learned all they knew about their local plants they would tell him that they learned what they knew from ayahuasca. Of course, Narby could not believe that a hallucinogen could impart real knowledge.

In the book Narby says, “After about a year in Quirishari, I had come to see that my hosts’ practical sense was much more reliable in their environment than my academically informed understanding of reality. Their empirical knowledge was undeniable. However, their explanations concerning the origins of their knowledge was unbelievable to me.”

One day while inquiring about these matters he was told that if he wanted to know the true answers to his questions he would simply have to take ayahuasca with them and see for himself. Narby accepted this offer and had a life changing experience. After drinking ayahuasca, Narby had a profound life changing experience. His view on himself and reality shifted from an intellectually superior know-it-all to a mere human being that has no real understanding of reality at all. In his experience, these thoughts were telepathically imparted to him by two giant snakes. There was more to his ayahuasca experience, but these are the elements that had the important impact on him.

In 1986 Narby returned to civilization to write his dissertation and two years later he became a doctor of anthropology. Following this he traveled around the Amazon working with indigenous organizations to earn them official governmental recognition of their territories. To these ends he also did fund-raising work in Europe. To appeal to benefactors Narby emphasized the practical knowledge of these Amazonian people, deliberately omitting the enigma of ayahuasca.

After some years of this kind of work, Narby set back to reflect upon and write about the mystery of ayahuasca. Much of this book is the story of how we came to write the book; a sort of boot-strapping process. Months of research and note-taking led Narby to many different topics including shamanism, ethnopharmacology, serpent myths, DNA, quantum physics and more.

As anyone who studies mythology, mysticism and occult traditions knows, the symbol of the serpent of the twin serpents as the creator of life is astoundingly ever-present as is what has been called the axis mundi or axis of the world. This latter concept has been symbolized as the world tree, the pillar of the worlds, the ladder connecting the earth to the upper and lower realms and so on. Often we see this central axis of the macrocosm mirrored in the central axis of the microcosm of the self in the form of the twin serpents. Consider the kundalini snakes that spiral up the spine in eastern mysticism or the spiraling snakes of the ancient Greek caduceus that is still used as the symbol of the medical profession. These symbols are found in ancient Egypt, in Sumerian and Babylonian frescos, among Siberian shamans who have never seen real snakes in their lives; consider Quetzalcoatl, the serpent-god of the Aztecs, the rainbow serpent and creator god of Australian aborigines, the Midgard serpent of Nordic myths wound about the world tree, the serpent and the Tree of Knowledge in the Judeo-Christian mythology and so on.

Through chance, synchronicity or some other cause Narby encountered many uncanny connections between this symbol complex and DNA without really knowing what it all meant. Here is the main thrust of Narby’s book, fueled by his own powerful experience with the two serpents he encountered in his ayahuasca experience years earlier.

Narby developed the hypothesis that somehow, through what Eliade called “archaic techniques of ecstasy” shamans receive information from DNA in the form of visions. Indeed, it is almost a universal truism that shamans gain their unique view on things by traveling up and down the axis mundi of the macrocosm or the microcosmic axis of the self.

Through his studies, Narby became engrossed in the molecular biology of DNA and he gives us many correlations between DNA and the shamanic world view. Close minded readers may find these to be mere circumstantial coincidences and gullible readers may find these to be proof that Narby’s hypothesis is correct. These correlations are truly astounding but far from conclusive. Narby does not pretend to have final answers but he definitely forces the reader to take these questions seriously as correlation after correlation pile up. These correlations or coincidences seemingly never end but Narby actually misses a few; that the ancient Chinese system of divination known as the I Ching there are 64 different symbols to cover the totality of possible phenomena in the universe and that there are 64 different codons or strands in DNA, or that DNA is made from 22 different amino acids and that in the ancient Greco-Egyptian system of the Tarot there are 22 cards in the major arcane sequence to cover the totality of possible phenomena in the universe but I digress or that the final card in this series uses the serpent as a symbol of the macrocosm of the world and eternity.

As many a student of the occult, mysticism and mythology has found, once you start unraveling these uncanny correlations and connections, it just gets deeper and deeper and that the more one looks for answers, the more questions arise without answers. There seems to be no end to this sort of inquiry. Indeed, as exhaustive as Narby seems to be in the exploration of his hypothesis, his book really only scratches the surface of the seemingly endless mystery we encounter in the shamanic realms.

The following passages sum up Narby’s hypothesis and position:

“I began my investigation with the enigma of “plant communication.” I went on to accept the idea that hallucinations could be the source of verifiable information. And I ended up with a hypothesis suggesting that a human mind can communicate in defocalized consciousness with the global network of DNA-based life. All this contradicts principles of Western knowledge.”

“Nevertheless, my hypothesis is testable. A test would consist of seeing whether institutionally respected biologists could find biomolecular information in the hallucinatory world of ayahuasqueros… My hypothesis suggests that what scientists call DNA corresponds to the animate essences that shamans say communicate with them and animate all life forms. Modern biology, however, is founded on the notion that nature is not animated by an intelligence and therefore cannot communicate. (page 132)”

“To sum up: My hypothesis is based on the idea that DNA in particular and nature in general are minded. (page 145)”

Along the way, we are given a dizzying dose of the mysterious nature of molecular biology. It is easy for the non-biologist to assume that this science is all tedious details of well-understood mechanisms but as Narby shows us, this science is just now tapping into the truly miraculous, bizarre and still fundamentally puzzling inner workings of the core of life.

It can not go unmentioned here that René Descartes became the “founder of modern philosophy” and the “father of modern mathematics” (as he is generally considered) after being inspired by a dream revelation in which an angel came to him and told him that “the conquest of nature is to be achieved through measure and number” and that this angelic revelation is the basis for the modern scientific method. Also, we should note that Kekulé discovered the benzene ring after dreaming about the Ouroboric serpent in the shape of a circle, swallowing its own tail. The idea that dreams could be a verifiable source of important scientific knowledge seems contradictory to science itself, yet many scientists have gained important knowledge this way. Here’s an even more startling example that brings us closer to the dual theme of Narby’s book; towards the end of his life, Francis Crick, the nobel-prize winning father of modern genetics confided a secret he kept for almost 50 years – that he hit upon the double helix structure of DNA while on LSD (see reference below). With this example of scientific knowledge derived from a hallucinogen, we see the snake swallowing its tail.

The Cosmic Serpent is similar to Terence McKenna’s True Hallucinations to the extent that both books give us accounts of Amazon excursions and experiences with plant hallucinogens imparting visions and ideas fecund with profound hypotheses involving the molecular biology of DNA. The Cosmic Serpent is similar to The Invisible Landscape by Terence and Dennis McKenna in that both of these books extrapolate upon such hypotheses in dizzying detail.

It should be noted that The Cosmic Serpent contains little in the way of descriptions of the ayahuasca experience. Readers looking for good trip stories would do better to look elsewhere.

This book is by no means light reading. Though not nearly as dense with complex details and wild extrapolations as the McKenna brother’s The Invisible Landscape, The Cosmic Serpent may contain far too detailed a discussion of molecular biology for many readers, though one certainly does not need a background in biology to understand Narby’s book, only an appreciation for the fascinating mysteries this science is just scratching the surface of.

Also, this book contains many long footnotes that some readers may find distracting or tedious while others may appreciate these details. Personally I found these details interesting but distracting. Many pages had multiple footnotes and sometimes the footnotes for a given page were longer than the page itself.

Overall, however, it is my opinion that this is a fascinating book. It brings up correlations or coincidences, raises questions and suggests ramifications that are too profound and challenging to go unexamined. The intelligent, discerning, but open-minded reader with a passion for the deepest mysteries of life and with an interest in both shamanism and science would be likely to find this book to be both important and amazing.

It is perhaps fitting to close this review with a quote from the book, “All things considered, wisdom requires not only the investigation of many things, but contemplation of the mystery.”

References:

Rees A. “Nobel Prize genius Crick was high on LSD when he discovered the secret of life” August 8, 2004 Associated Newspapers Ltd. (London)

Originally Published In: Amazon.com

|

Could you sum up your book "The Cosmic Serpent, DNA and the Origins of Knowledge"?

Research indicates that shamans access an intelligence, which they say is nature's, and which gives them information that has stunning correspondences with molecular biology.

Your hypothesis of a hidden intelligence contained within the DNA of all living things is interesting. What is this intelligence?

Intelligence comes from the Latin inter-legere, to choose between.

- There seems to be a capacity to make choices operating inside each cell in our body, down to the level of individual proteins and enzymes.

- DNA itself is a kind of "text" that functions through a coding system called "genetic code," which is strikingly similar to codes used by human beings.

- Some enzymes edit the RNA transcript of the DNA text and add new letters to it; any error made during this editing can be fatal to the entire organism; so these enzymes are consistently making the right choices; if they don't, something often goes wrong leading to cancer and other diseases.

- Cells send one another signals, in the form of proteins and molecules.

- These signals mean: divide, or don't divide, move, or don't move, kill yourself, or stay alive.

- Any one cell is listening to hundreds of signals at the same time, and has to integrate them and decide what to do.

- How this intelligence operates is the question.

DNA has essentially maintained its structure for 3.5 billion years. What role does DNA play in our evolution?

|

DNA is a single molecule with a double helix structure;

- It is two complementary versions of the same "text" wrapped around each other;

- This allows it to unwind and make copies of itself: twins!

- This twinning mechanism is at the heart of life since it began. Without it, one cell could not become two, and life would not exist.

- And, from one generation to the next, the DNA text can also be modified, so it allows both constancy and transformation.

- This means that beings can be the same and not the same.

One of the mysteries is what drives the changes in the DNA text in evolution.

- DNA has apparently been around for billions of years in its current form in virtually all forms of life.

- The old theory — random accumulation of errors combined with natural selection — does not fully explain the data currently generated by genome sequencing.

- The question is wide open.

The structure of DNA as we know it is made up of letters and thus has a specific text and language. You could say our bodies are made up of language, yet we assume that speech arises from the mind. How do we access this hidden language?

By studying it. There are several roads to knowledge, including science and shamanism.

The symbol of the Cosmic Serpent, the snake, is a central theme in your story, and in your research you discover that the snake forms a major part of the symbology across most of the world’s traditions and religions. Why is there such a consistent system of natural symbols in the world? Is the world inherently symbolic?

This is the observation that led me to investigate the cosmic serpent.

- I found the symbol in shamanism all over the world. Why? That's a good question.

- My hypothesis is that it is connected to the double helix of DNA inside virtually all living beings.

- And DNA itself is a symbolic Saussurian code.

- So, yes, in at least one important way, the living world is inherently symbolic. We are made of living language.

You write of how the ideology of "rational" science, deterministic thought, is and has been quite limiting in its approach to new and alternative scientific theories; it is assumed that "mystery is the enemy." In your book you describe how you had to suspend your judgement, to "defocalize," and in this way gain a deeper insight. Why do you think we are often limited in our rational, linear thought and why are so few willing and able to cross these boundaries?

Vision of the Snakes

By Pablo Amaringo | Gallery of Usko-Ayar Art |

I don't believe we are. People spend hours each day thinking non-rationally.

- Our emotional brain treats all the information we receive before our neo-cortex does.

- Scientists are forever making discoveries as they daydream, take a bath, go for a run, lay in bed, and so on.

What are the correspondences between the Peruvian shamans’ findings and microbiology?

Both shamans and molecular biologists agree that there is a hidden unity under the surface of life's diversity;

- Both associate this unity with the double helix shape (or two entwined serpents, a twisted ladder, a spiral staircase, two vines wrapped around each other);

- Both consider that one must deal with this level of reality in order to heal.

- One can fill a book with correspondences between shamanism and molecular biology.

Do you think there is not only an intelligence based in our DNA but a consciousness as well?

I think we should attend to the words we use. "Consciousness" carries different baggage than "intelligence."

- Many would define human consciousness as different from, say, animal consciousness, because humans are conscious of being conscious.

- But how do we know that dolphins don't think about being dolphins?

- I do not know whether there is a "consciousness" inside our cells; for now, the question seems out of reach; we have a hard enough time understanding our own consciousness — though we use it most of the time.

- I propose the concept of "intelligence" to describe what proteins and cells do, simply because it makes the data more comprehensible.

- This concept will require at least a decade or two for biologists to consider and test.

- Then, we might be able to move along and consider the idea of a "cellular consciousness."

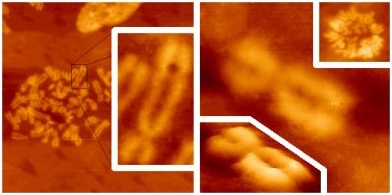

Alchemical vision of chromosomal DNA?

|

The implications of some of your findings in The Cosmic Serpent could be quite large. How do you feel about the book and what it says? Why did you write the book?

I wrote the book because I felt that certain things needed saying.

- Writing a book is like sending out a message in a bottle: sometimes one gets replies.

- Judging from the responses, a surprising number of people have got the message loud and clear.

How can shamanism complement modern science?

Most definitions of "science" revolve around the testing of hypotheses.

- Claude Levi-Strauss showed in his book The Savage Mind that human beings have been carefully observing nature and endlessly testing hypotheses for at least ten thousand years.

- This is how animals and plants were domesticated.

- Civilization rests on millennia of Neolithic science.

- I think the science of shamans can complement modern science by helping make sense of the data it generates.

- Shamanism is like a reverse camera relative to modern science.

The shamans were very spiritual people. Has any of this affected you? What is spiritual in your life?

I don't use the word "spiritual" to think about my life.

Actual photo of chromosomal DNA.

|

- I spend my time promoting land titling projects and bilingual education for indigenous people, and thinking about how to move knowledge forward and how to open up understanding between people;

- I also spend time with my children, and with children in my community (as a soccer coach);

- And I look after the plants in my garden, without using pesticides and so on.

- But I do this because I think it needs doing, and because it's all I can do, but not because it's "spiritual."

- The message I got from shamans was: do what you can for those around you (including plants and animals), but don't make a big deal of it.

|

Note on the translation: The author wrestled the text Most Tarcher/Putnam books are available at special quantity discounts for bulk purchases Special books or book excerpts also can be created to fit specific needs. For details, write Putnam Special Markets, Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam www.penguinputnam.com First Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam trade paperback edition 1999 Copyright © 1998 by Jeremy Narby All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, Published simultaneously in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Narby, Jeremy. [Serpent cosmique. English] The cosmic serpent : DNA and the origins of knowledge / by Jeremy Narby. Includes bibliographical references. eISBN : 978-1-101-49435-6 1. Indians of South America—Drug use—Peru. 2. Shamanism—Peru. 3. Hallucinogenic drugs—Peru

http://us.penguingroup.com |

|

To |

| Many thanks to the following: | |

|

■ first reader: ■ research assistant: ■ third base coach: ■ unconditional support: ■ epistemology: ■ anthropology: ■ metaphysics: ■ biology: ■ botany: ■ medicine: ■ professional guidance: ■ argumentation: ■ French language consultant: ■ images ■ literary agent: ■ the term “DNA-TV” ■ original readers: ■ English manuscript readers: ■ my professors: |

■ my colleagues: ■ nicotinic receptors: ■ dimethyltryptamine information ■ nicotine information: ■ stereograms: ■ child care: ■ Books: ■ Flashback Books: ■ In Peru: ■ Original fieldwork funded by: ■ Specials thanks go to: |

p. 49. “The human brain.... Redrawn from Desana sketches.” From G. Reichel-Dolmatoff, “Brain and Mind in Desana Shamanism,” in Journal of Latin American Lore, vol. 7, no. 1 (1981). Reprinted with permission of The Regents of the University of California.

p. 50. “The human brain.... Redrawn from Desana sketches.” From G. Reichel-Dolmatoff, “Brain and Mind in Desana Shamanism,” in Journal of Latin American Lore, vol. 7, no. 1 (1981). Reprinted with permission of The Regents of the University of California.

p. 55. “The ancestral anaconda . . . guided by the divine rock crystal.” From G. Reichel-Dolmatoff, “Brain and Mind in Desana Shamanism,” in Journal of Latin American Lore, vol. 7, no. 1 (1981). Reprinted with permission of The Regents of the University of California.

p. 55. “The Serpent Lord Enthroned.” From J. Campbell (1964), p. 11. New York, Viking, all rights reserved.

p. 56. “Zeus against Typhon.” From J. Campbell (1964), p. 239. New York, Viking, all rights reserved.

p. 58. (No title.) From Luna and Amaringo (1991), “Vision 33: Campana Ayahuasca,” p. 113. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

p. 58. “. . . the spread-out form of DNA . . .” From Luna and Amaringo (1991), “Vision 46: Sepultura Tonduri,” p. 139. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

p. 58. “. . . chromosomes at a specific phase. . . .” From Luna and Amaringo (1991), “Vision 40: Ayacatuca,” p. 127. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

p. 58. “. . . triple helixes of collagen . . .” From Luna and Amaringo (1991), “Vision 21: The Sublimity of the Sumiruna,” p. 89. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

p. 58. “. . . DNA from afar, looking like a telephone cord . . .” From Luna and Amaringo (1991),

“Vision 32: Pregnant by an Anaconda,” p. 111. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

p. 61. Cover of Crick (1981) is reprinted with the kind permission of Little, Brown & Co.

p. 64. “A painting on hardboard of the Snake of the Marinbata people of Arnhem Land.” From F. Huxley (1974), p. 127. Photo by Axel Poignant. All rights reserved.

p. 64. “A rock painting of the Walbiri tribe of Aborigines representing the Rainbow Snake.” From F. Huxley (1974), p. 126. Photo by David Attenborough. All rights reserved.

p. 64. “Early prophase . . .” From Watson et al. (1987). Copyright © 1987 by James D. Watson. Published by the Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company.

p. 64. “Anaphase II . . .” From Watson et al. (1987). Copyright © 1987 by James D. Watson. Published by the Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company.

p. 65. “The cosmic serpent, provider of attributes.” From R. T. R. Clark (1959), p. 52. Reprinted with permission from Thames and Hudson Ltd.

p. 65. “Sito, the primordial serpent.” From R. T. R. Clark (1959), p. 192. Copyright British Museum.

p. 65. “Ronín, the two-headed serpent.” From A. Gebhart-Sayer (1987), p. 42. Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 65. “The serpent of the earth becomes celestial ...” From C. Jacq (1993), p. 99. Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 66. “Here is the dragon that devours its tail.” From M. Maier (1965, orig. 1618), p. 139. All rights reserved.

p. 66. “Ouroboros: bronze disk, Benin art.” From Chevalier and Gheerbrant (1982), p. 716. Paris, Robert Laffont, all rights reserved.

p. 67. “Vishnu and his wife Lakshmi resting on Sesha . . .” From F. Huxley (1974), pp. 188-89. Reprinted with the kind permission of Aldus Books and the Ferguson Publishing Company.

p. 68. “Cosmovision.” From A. Gebhart-Sayer (1987), p. 26. Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 68. “Aspects of Ronín.” From A. Gebhart-Sayer (1987), p. 34. Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 69. (No title.) From J. Watson (1968), p. 165. London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, all rights reserved.

p. 71. “The DNA double helix represented as a pair of snakes...” From Wills (1991), p. 37. Copyright © 1991 by Christopher Wills. Reprinted by permission of Basic Books, a division of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

p. 72. “Liana (Bauhinia caulotretus) ‘that goes from earth up to heaven.’” From T. Koch-Grünberg (1917), vol. 2, drawing IV. All rights reserved.

p. 73. “The ‘sky-ladder’ drawing . . .” From A. Gebhart-Sayer (1987). Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 74. “Banisteriopsis caapi, a liana that tends to grow in charming double helices ...” From Schultes and Raffauf (1992), p. 26. Reprinted with permission from Synergetic Press, Oracle, Arizona.

p. 78. “The cosmic serpent, provider of attributes.” From R. T. R. Clark (1959), p. 52. Reprinted with permission from Thames and Hudson Ltd.

p. 80. “A magnified section of a leaf . . .” From a photo by Alfred Pasieka. Reprinted with the photographer’s permission.

p. 84. “Cosmovision.” From A. Gebhart-Sayer (1987), p. 26. Reprinted with the author’s kind permission.

p. 87. “Detail from Pablo Amaringo’s painting ‘Pregnant by an Anaconda.’” From Luna and Amaringo (1991), p. 111. Reprinted with the authors’ kind permission.

This over one hour long documentary features discussions by Jeremy Narby, a Canadian anthropologist living in Switzerland, who has made an extensive study of the indigenous use of ayahuasca in South American cultures. He has written one of the most interesting books about ayahuasca – The Cosmic Serpent – DNA and the Origins of Knowledge. In it, he compares the descriptions of the ayahuasqueros’s visions of intertwining serpents with molecular geneticists description of the DNA molecule, which has the structure of a double helix. Michael Harner, President of the Foundation for Shamanic Studies and author of The Way of the Shaman, wrote of The Cosmic Serpent that “it is a spellbinding, scholarly tour de force that may presage a major paradigm in the Western view of reality.”

Narby has also taken a small group of Western-trained scientists (geneticists, molecular biologists) to visit with ayahuasca shamans and found that they could indeed, with the help of the visionary vine, look directly into the deep subjective structure of the material world that they had previously studied intensively through their objective instruments and measures.