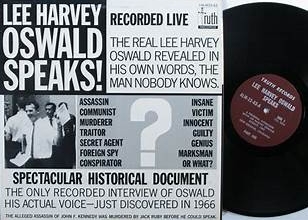

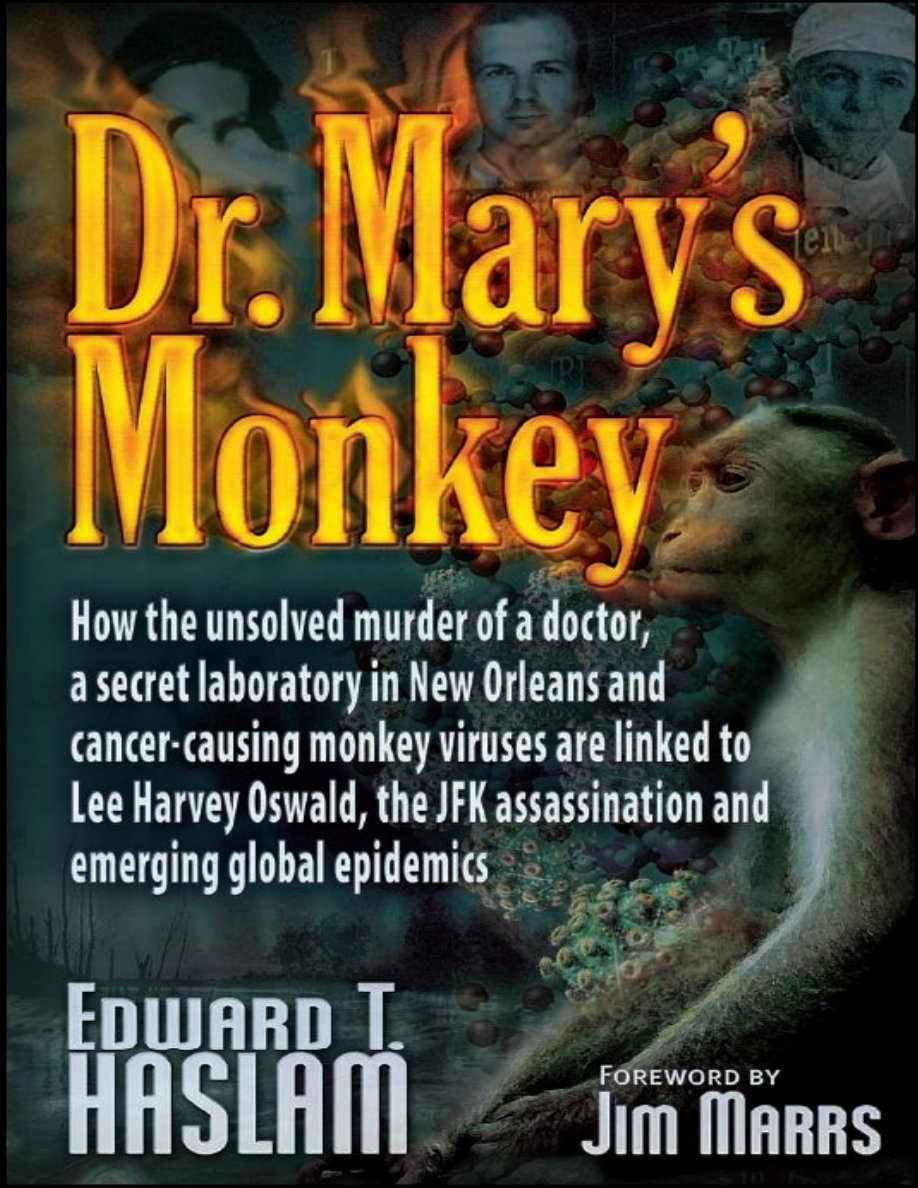

| Dr. Mary's Monkey | Source |

|

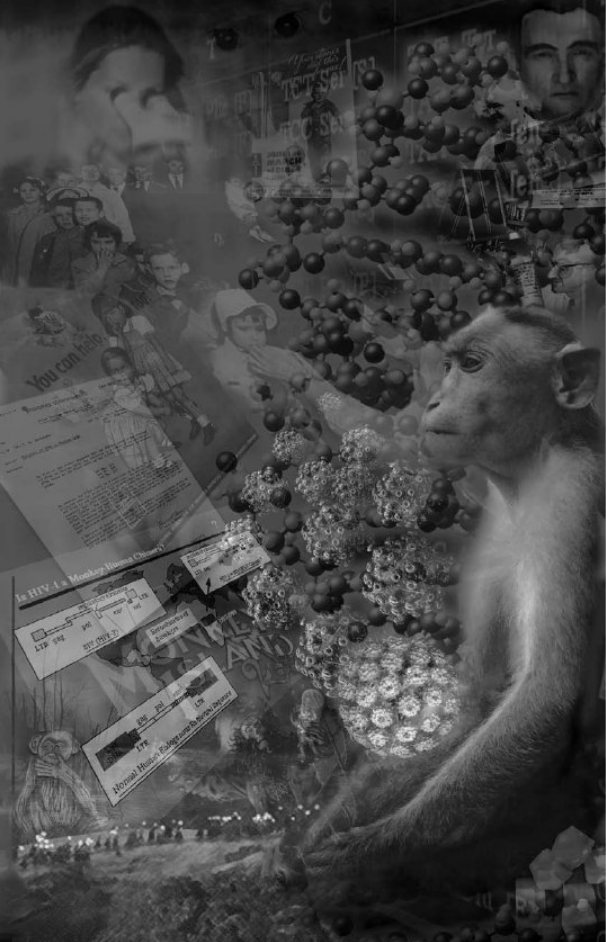

Did inoculating millions of trusting schoolchildren with polio vaccines contaminated by monkey viruses trigger an epidemic of soft-tissue cancers?

Was a desperate effort to develop an anti-cancer vaccine diverted secretly into biological weapons?

Is there a link between these covert experiments and AIDS? And do the answers to these vexing questions connect to the intrigues swirling around the assassination of President Kennedy?

More than a spirited page-turner, this riveting fresh look at a cold-case murder mystery is bound to make its own headlines. Here is a book of profound importance that helps us fathom what has really happened in our country. The grisly homicide of a nationally-known surgeon in 1964 New Orleans set the stage for a chilling exposé of scientists and spooks in shadowy hidden laboratories.

What they did then… affects our world today!

When New Orleans native Ed Haslam began his modest investigation into the curious life and shocking death of the brilliant Tulane medical professor Dr. Mary Sherman, he couldn't have imagined that this inquiry would connect some of the city's most prominent citizens to "lone-nut" Lee Harvey Oswald, the Mafia, and to forces high inside the U.S. Government — nor that these new discoveries would ultimately change our understanding of a fateful November day in Dallas. But they have!

Edward T. Haslam is an advertising executive who has represented some of the largest corporations in America. Originally from New Orleans, he has lived in Florida since 2000.

Foreword Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Appendix Epilogue |

Dedication By Jim Marrs The Warning The Pirate The Classroom Jimbo College Daze A Bishop in His Heart Mary, Mary The Cure for Communism Dr. O The Treatise The Fire The Machine That Other Epidemic The Witness The Teacher Judyth’s Story The Perfect Patsy Documents Bibliography |

iii iv v 1 8 12 16 20 28 34 38 44 51 54 60 63 73 75 80 87 97 |

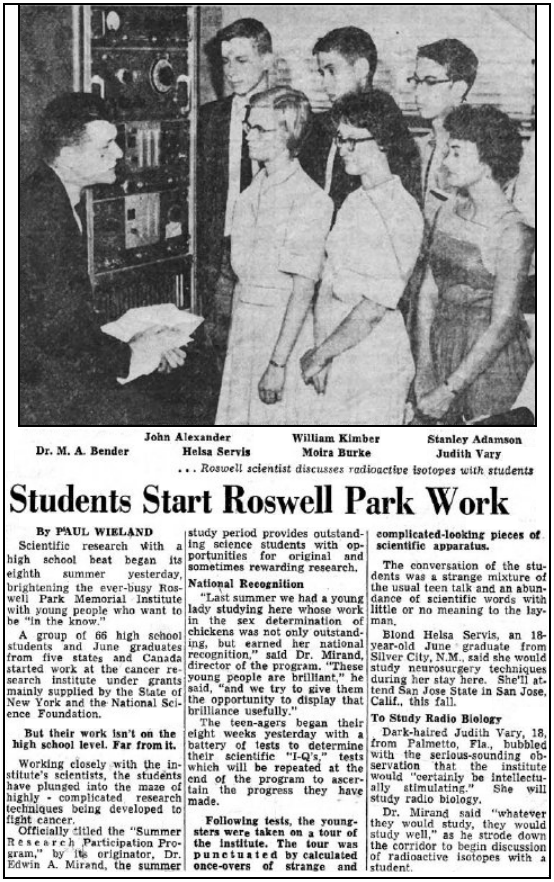

Dedicated to my father:

|

Edward T. Haslam, M. D.

1915-1971

Commander, United States Navy

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery

Tulane University, New Orleans

A doctor committed to upholding medical ethics.

There is nothing new to learn about the assassination of JFK.

WORDS LIKE THESE HAVE BE COME ALMOST a mantra among sanctimonious media pundits and complacent publishers. The problem is that they’re not true.

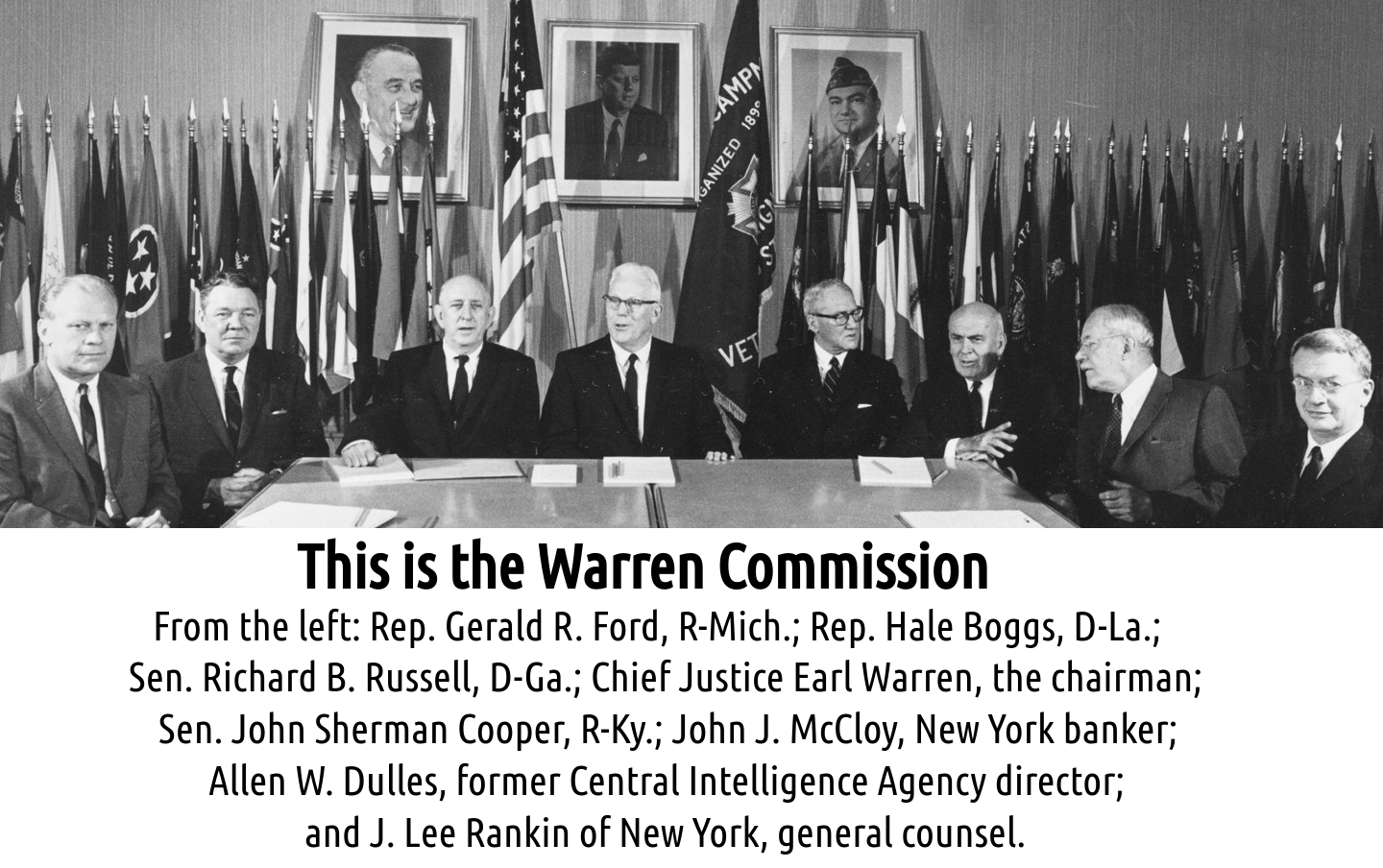

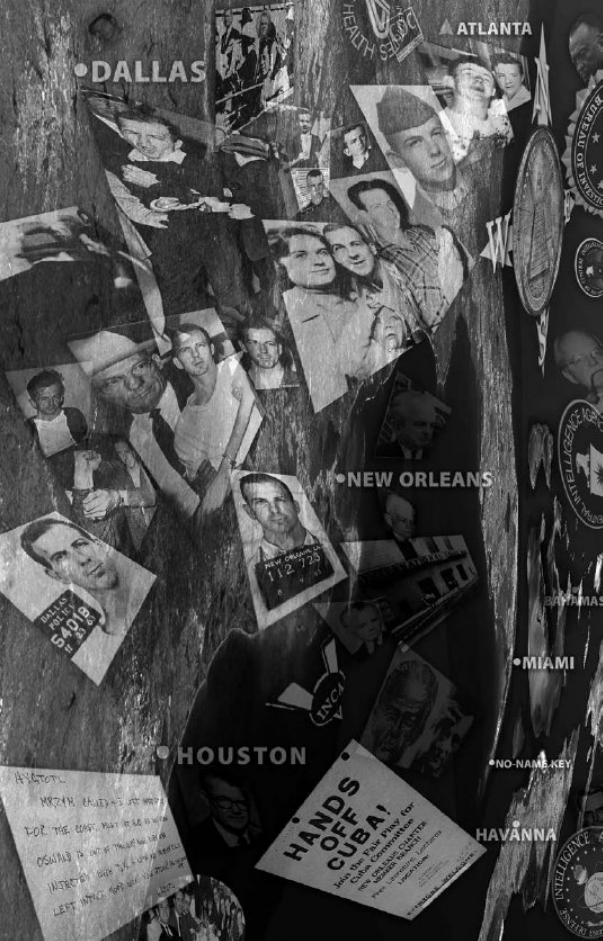

In this book, Ed Haslam takes our knowledge of the dark underpinnings of the 1960s to a new level by offering a whole new look at events surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. He focuses on activities in New Orleans during 1963, reaching far beyond Lee Harvey Oswald’s leafleting or his contacts with anti-Castro Cubans, government agents and mobsters.

Anyone who has seen the Oliver Stone film JFK or has read one of the many books on the assassination knows of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s ill-fated prosecution of International Trade Mart Director Clay Shaw.

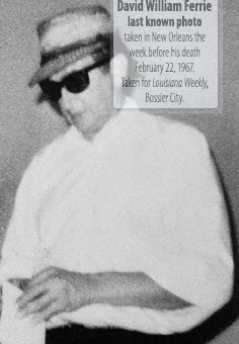

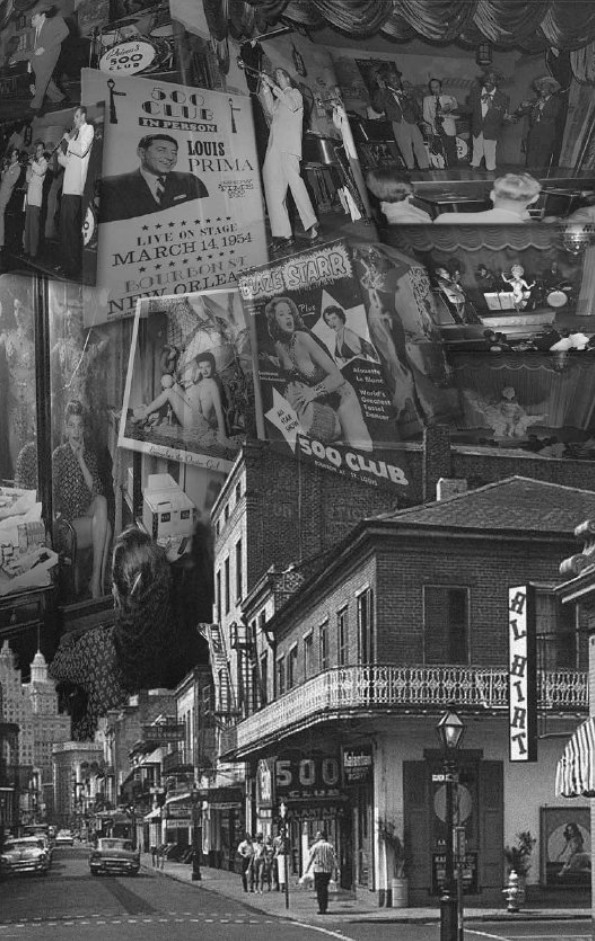

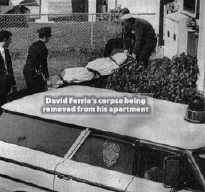

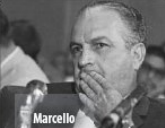

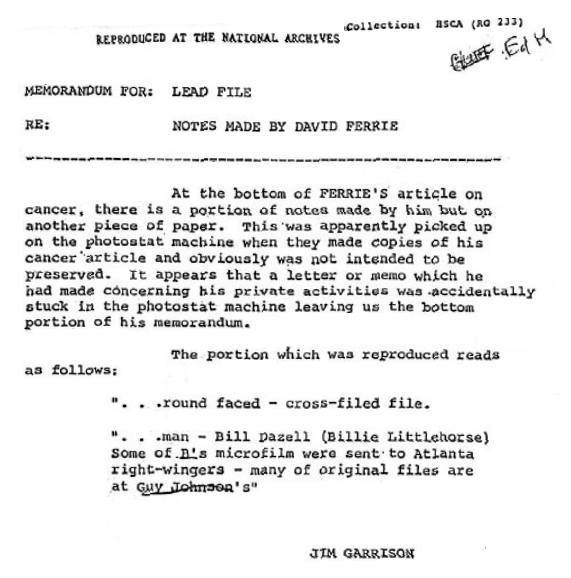

We know of Guy Banister, the ex-FBI agent who was connected to the CIA, anti-Castro Cubans and the accused assassin Oswald. We know of David Ferrie, a defrocked priest who was connected to the Mafia, the CIA and Oswald.

Shaw was able to successfully argue that he had never met Ferrie or Oswald. Today, we know that claim is simply untrue.

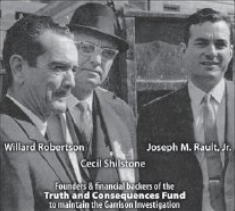

It is now well-accepted that officials within the federal government of the United States of America took steps to effectively block and derail Garrison’s probe. It seemed the New Orleans investigation was at an end.

But what if all that activity in New Orleans had nothing to do with the assassination? What if there was some other reason for sabotaging Garrison’s investigation?

After all, there is not one hard piece of evidence linking the Shaw-Ferrie axis to the events in Dealey Plaza. Ferrie, the man connected to Oswald, the Mob and the CIA, never got closer to Dallas than a Houston phone booth, and there was never any serious accusation that Clay Shaw went to Dallas.

Could there have been a deeper secret reason why the Garrison investigation had to be shut off? And could that reason have had more to do with contaminated polio vaccines and the secrecy of a deadly biological weapon experiment than any plotting against President Kennedy?

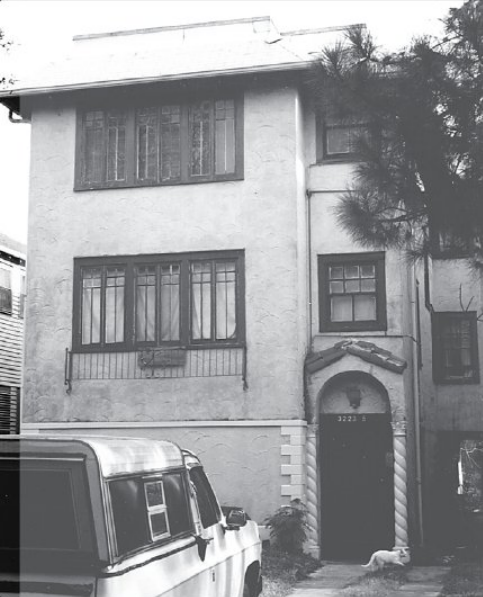

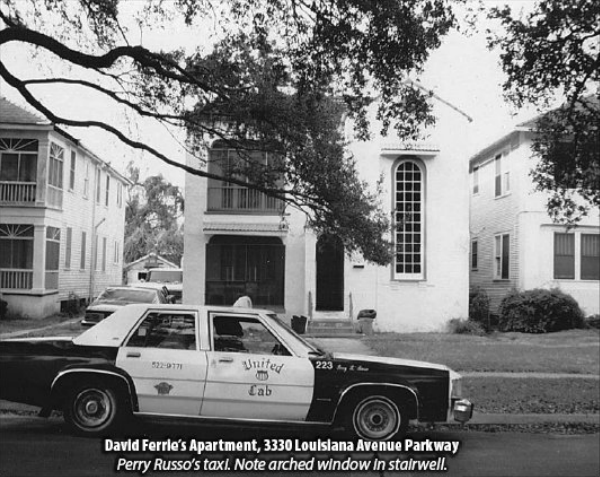

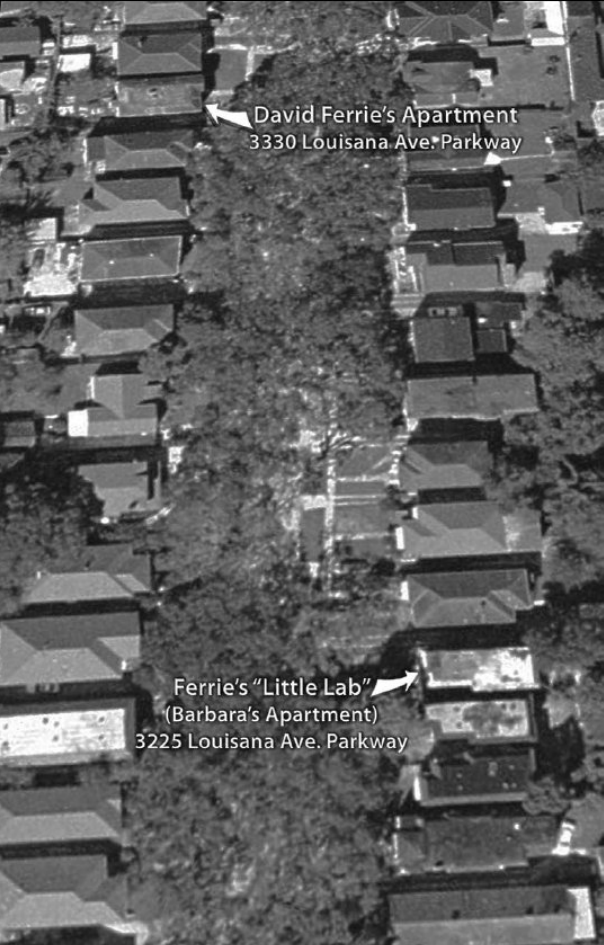

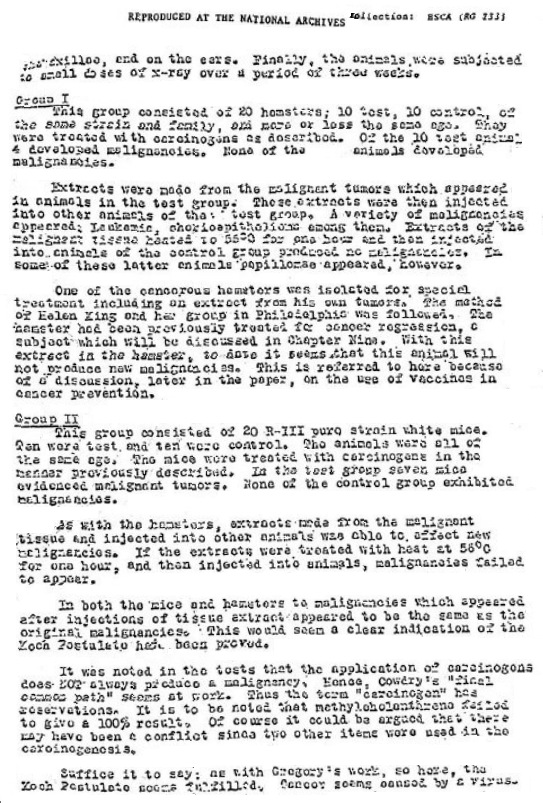

In his 1995 book Mary, Ferrie & the Monkey Virus, Haslam opened a whole new can of worms when he revealed the medical experiments that had taken place in David Ferrie’s apartment in 1963.

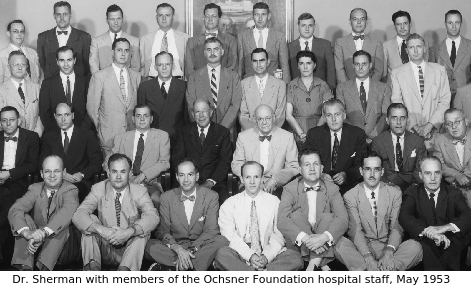

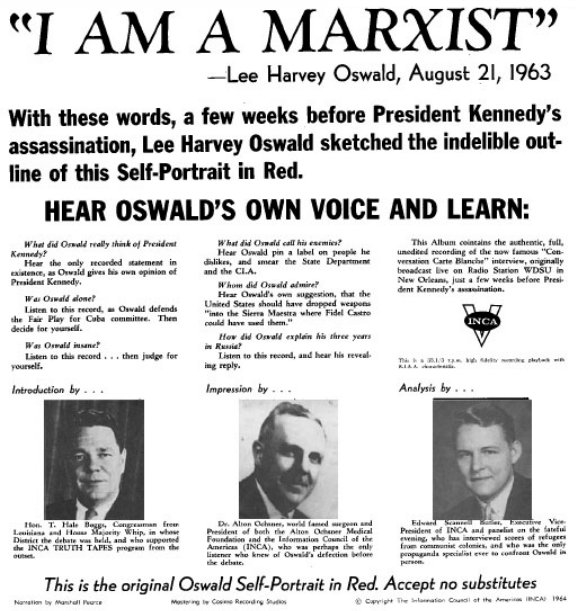

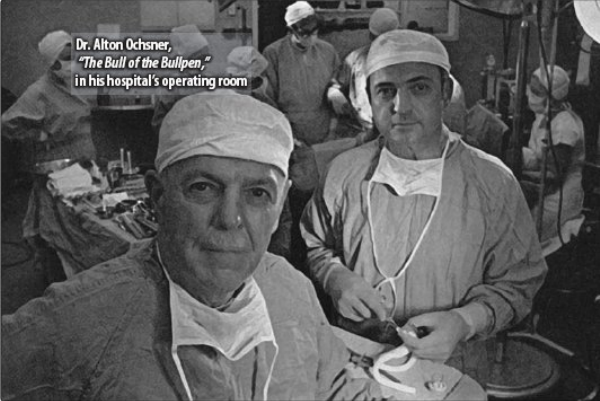

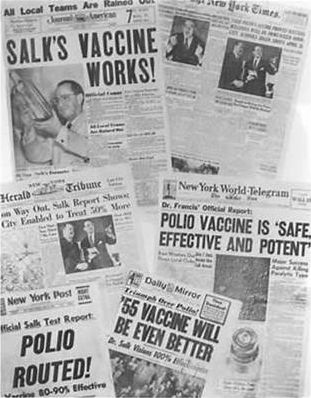

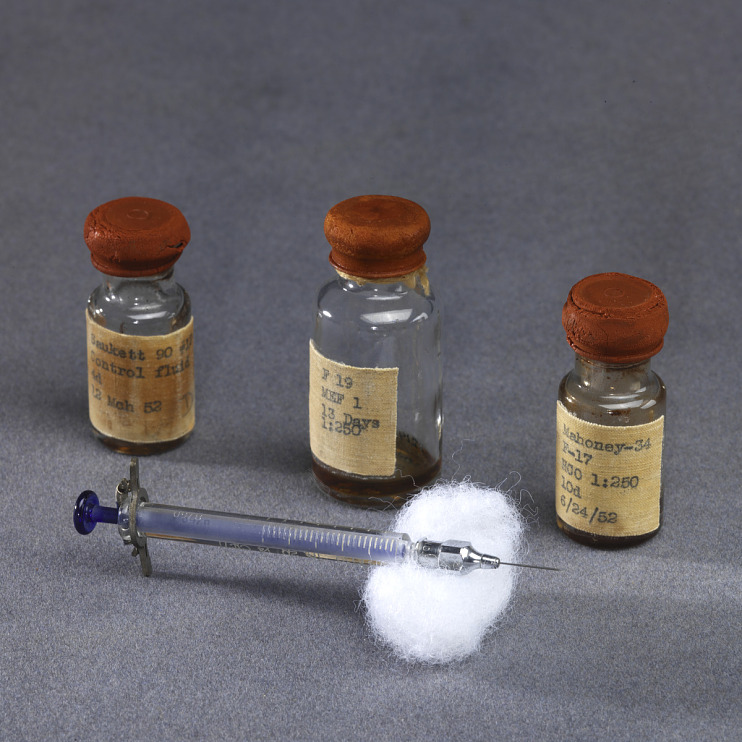

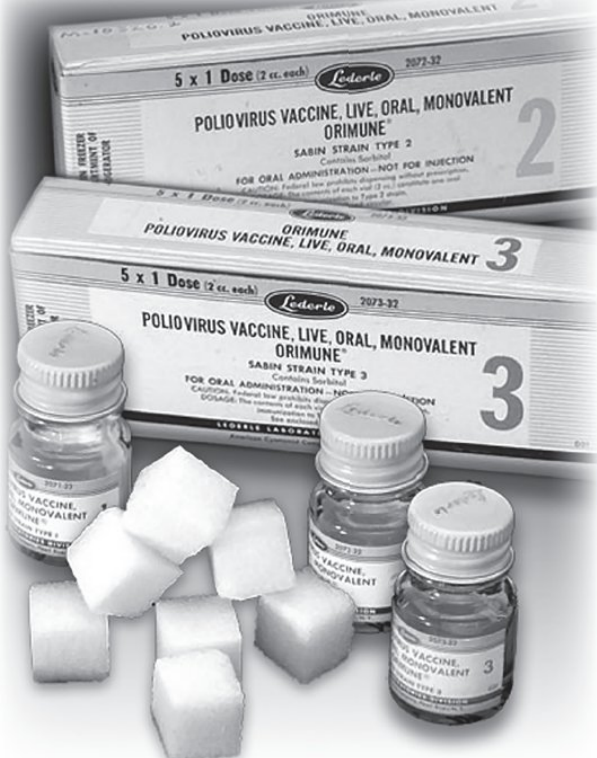

He was one of the first to bring to the public the now well-documented story of how the polio vaccines of the 1950s was adulterated with a cancer-causing virus derived from monkey glands. Federal certification officers were aware of the possibility of the polio vaccine being defective but were pressured into approving the vaccine by powerful medical interests, including Dr. Alton Ochsner of New Orleans.

Once the magnitude of the cancer-causing viruses in the polio vaccines became known, a massive covert effort was undertaken in an attempt to find a cure or preventative. All this was clandestine work, very hush-hush. No one wanted the American public to know that the polio vaccines inoculated into millions of our citizens were contaminated with dangerous monkey viruses, perhaps causing the cancer epidemic of recent years.

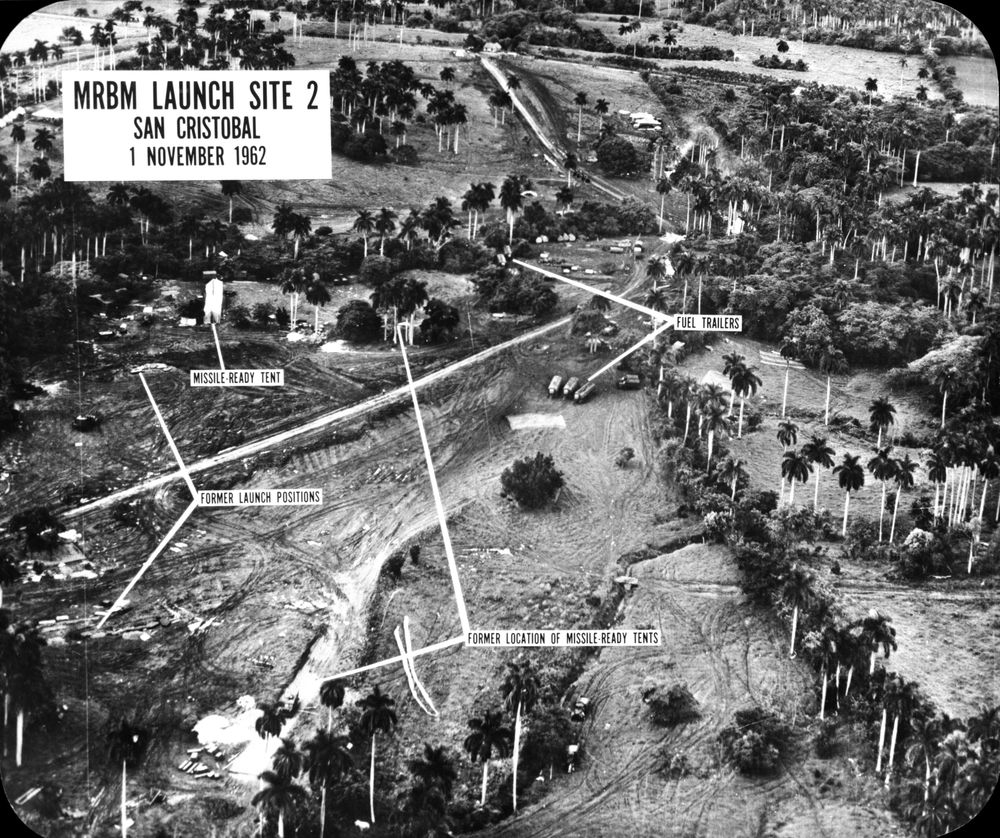

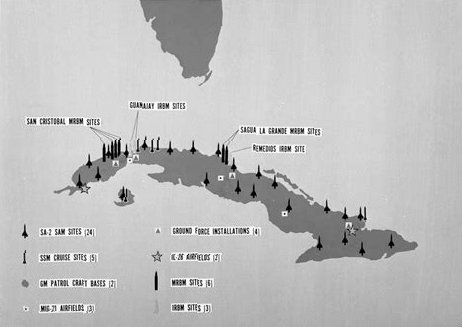

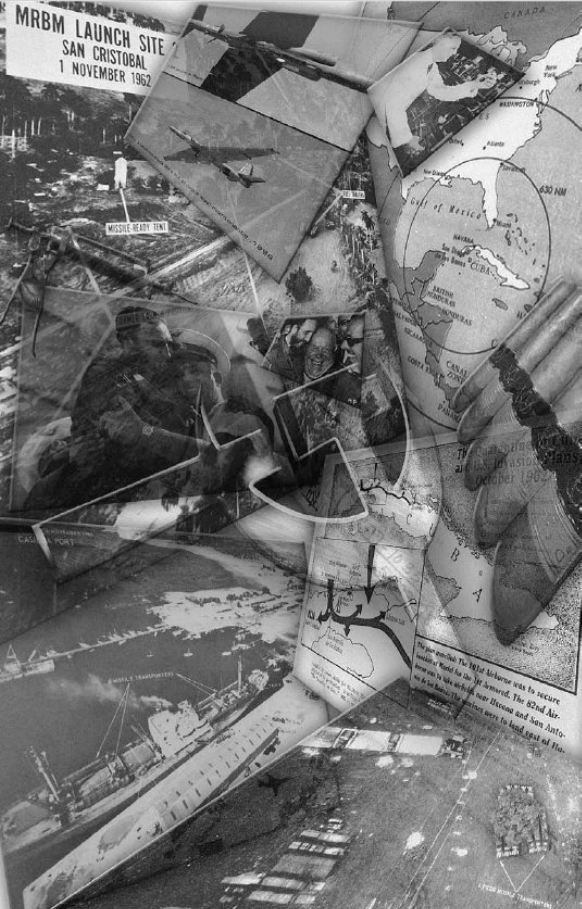

But then the story took an even darker turn: the CIA began to take an interest in the work. After all, this was a time when documented efforts were under way to find a subtle way of assassinating Fidel Castro. Military and intelligence eyes sparkled at the prospect of somehow injecting Castro with cancer. His death would appear natural, and there would be no accusations from the Soviet Union.

But what was Oswald’s role in all this activity? The evidence of Oswald’s intelligence work for the U.S. Government is overwhelming. Did he become involved in a biological weapons experiment so monstrous that its secret had to be maintained at all costs?

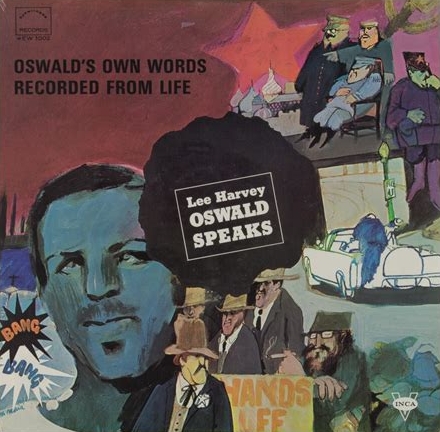

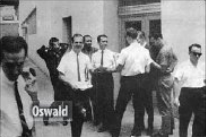

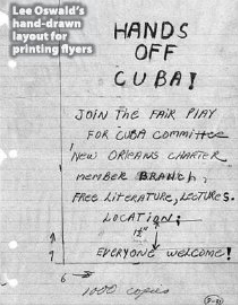

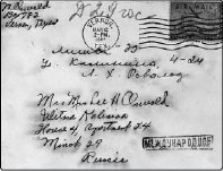

Diligent researchers know that Oswald was playing intelligence games in New Orleans in the summer of 1963. One day he was handing out pro-Castro literature on street corners, some of it stamped with the same address as Banister’s anti-Castro office at 544 Camp Street. Another day, Oswald was offering his services to anti-Castro militant Carlos Bringuier. Oswald’s duplicity resulted in what appeared to authorities as a staged fight between Oswald and Bringuier on a New Orleans street.

Oswald was arrested for disturbing the peace. While in jail, he did not ask to see a lawyer but instead someone from the FBI. Despite being outside normal business hours, FBI Agent John Quigley arrived and spent more than an hour with Oswald, who commenced to detail his activities since arriving in New Orleans, almost as though he was making a report to superiors. Yet Oswald made no public mention of David Ferrie or his work at Ferrie’s cancer lab.

According to information gathered by Haslam, Oswald also was much more closely connected to his uncle, Charles “Dutz” Murret, and New Orleans crime lord Carlos Marcello than previously suspected.

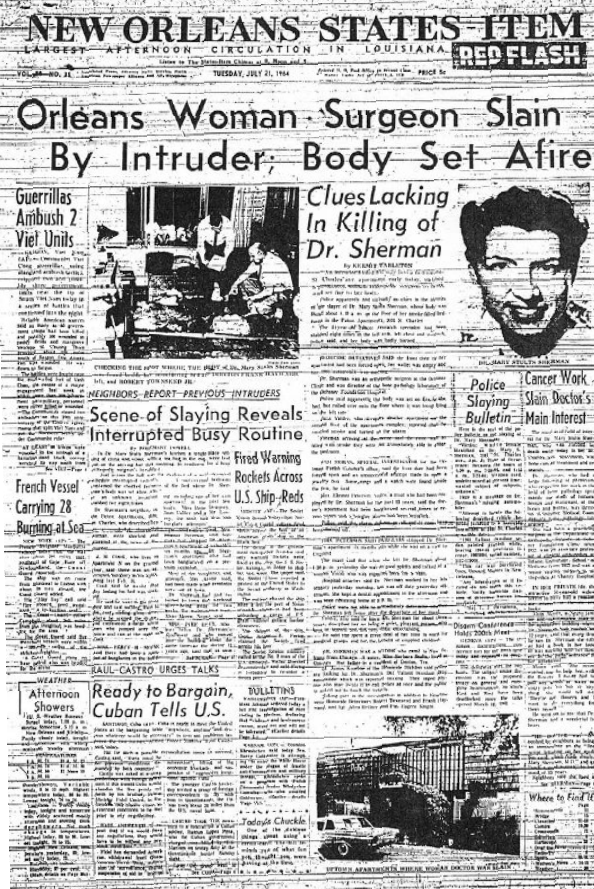

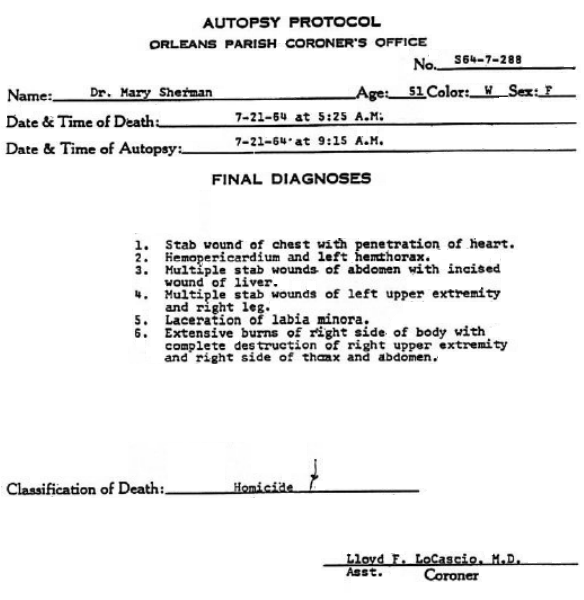

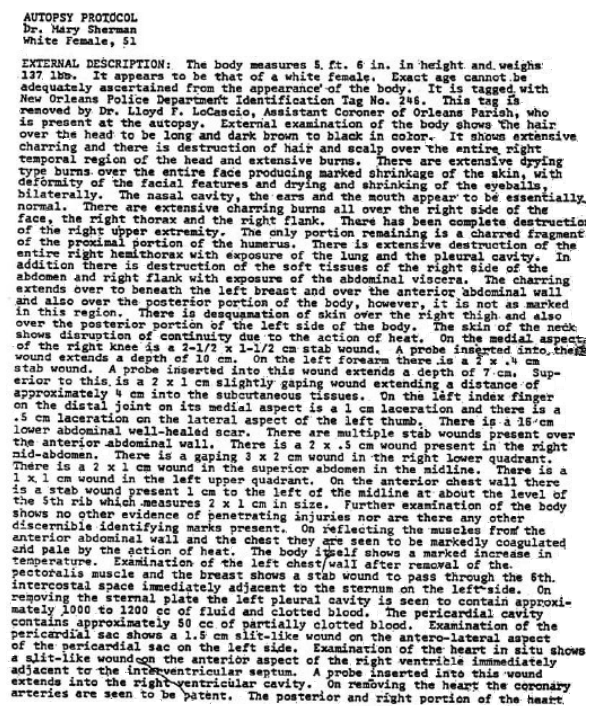

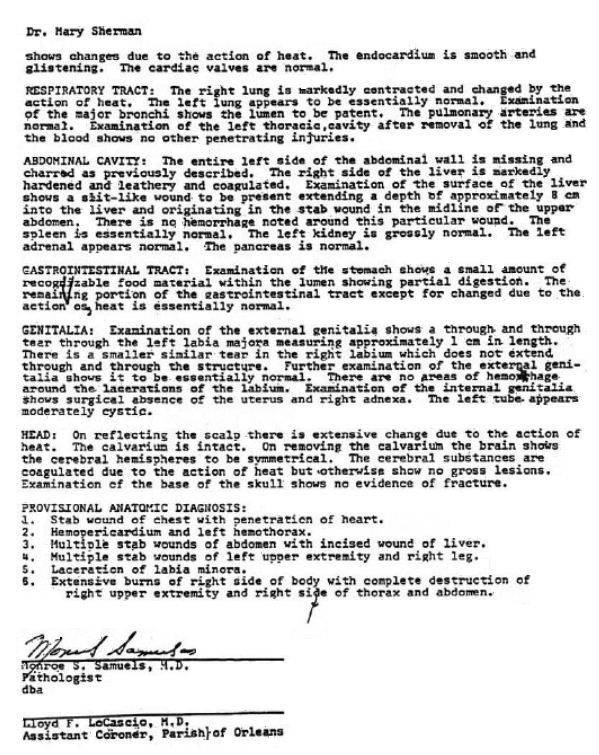

But Haslam’s primary focus is on the strange and horrible death of Dr. Mary Sherman, whose charred body was found in her home in July 1964. She had been stabbed multiple times. Her body exhibited the effects of extreme scorching and heat, yet there was only superficial fire damage to her bed and home.

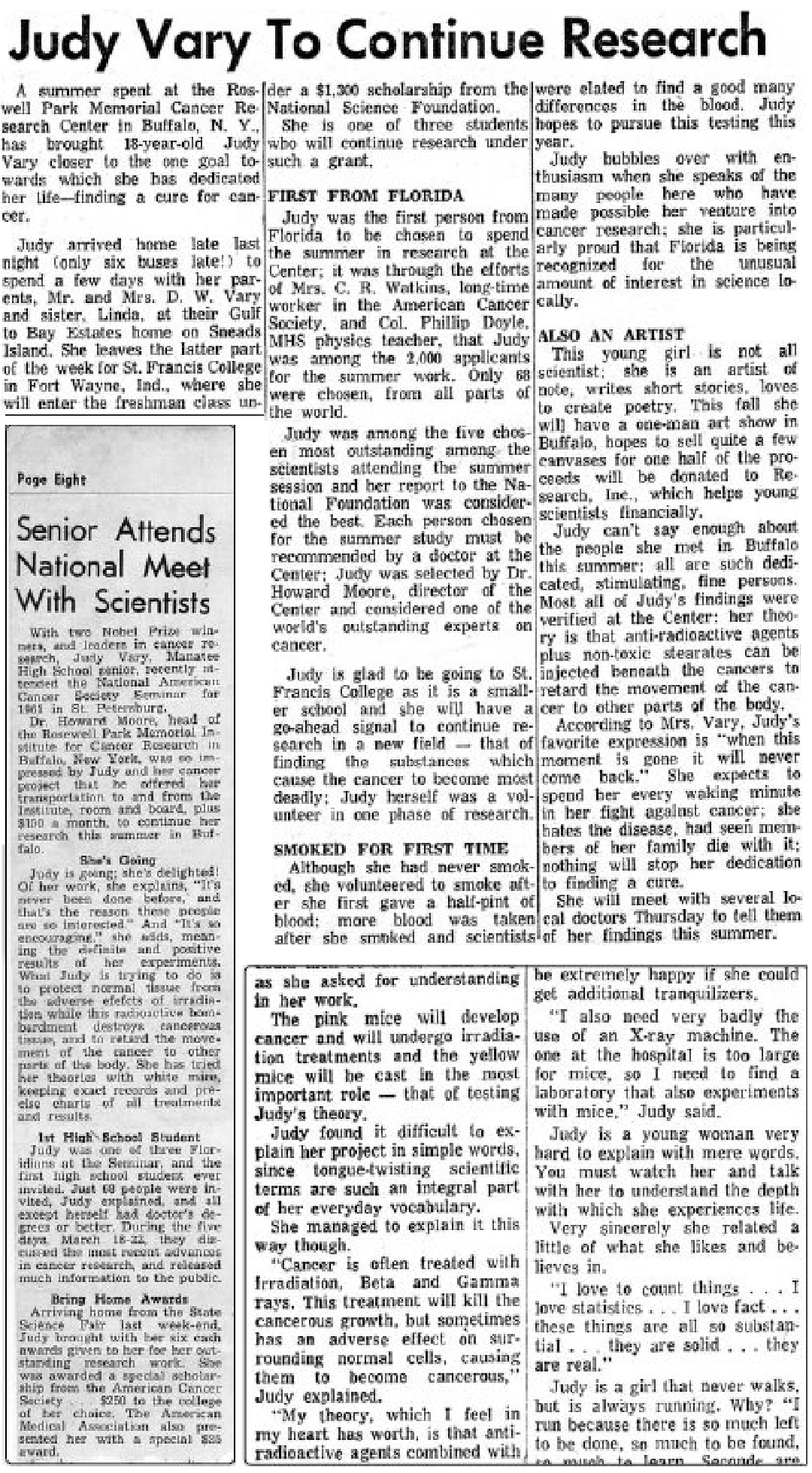

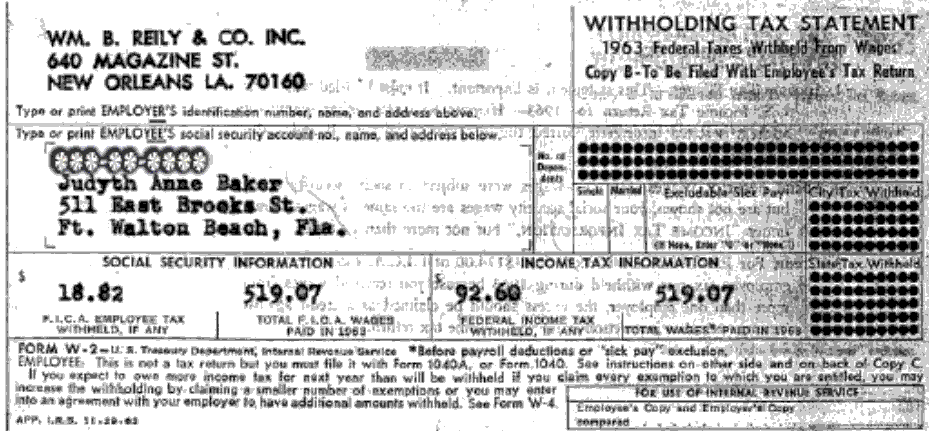

He also delves into Oswald’s work with Ferrie in the covert cancer lab and its fatal results. His research provides a plausible explanation for the caged white mice reported in Ferrie’s apartment, Oswald’s missing time at the Reily Coffee Company, and for the never fully understood trip to Clinton, LA, by Oswald, Ferrie and Shaw.

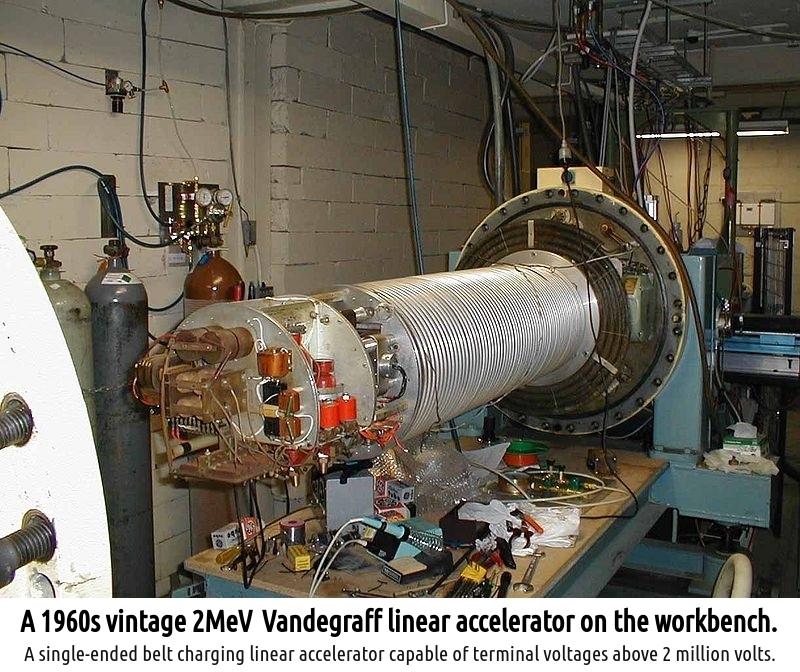

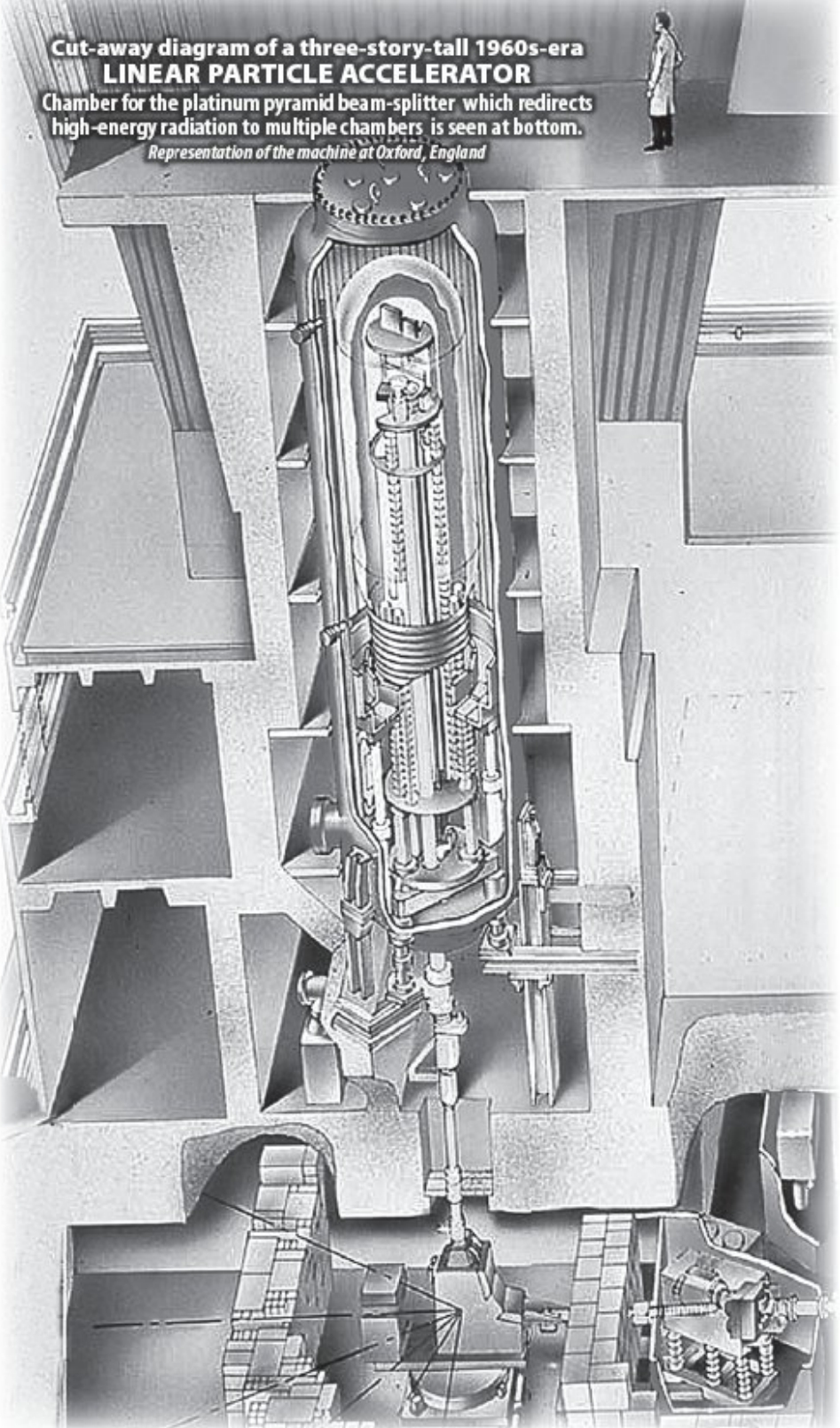

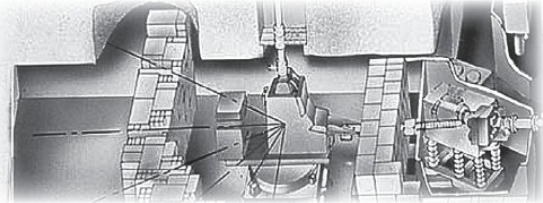

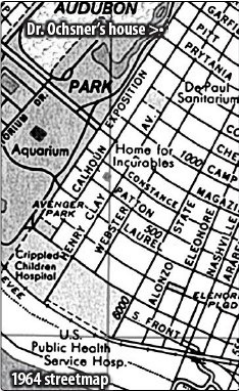

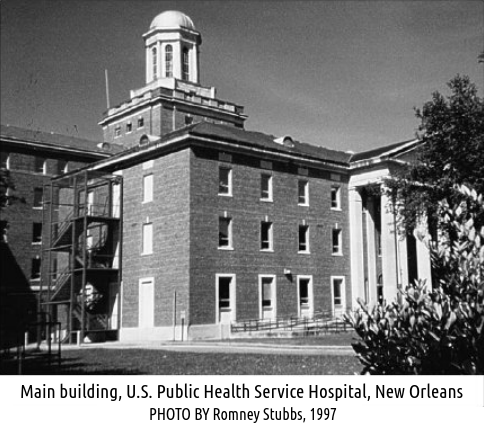

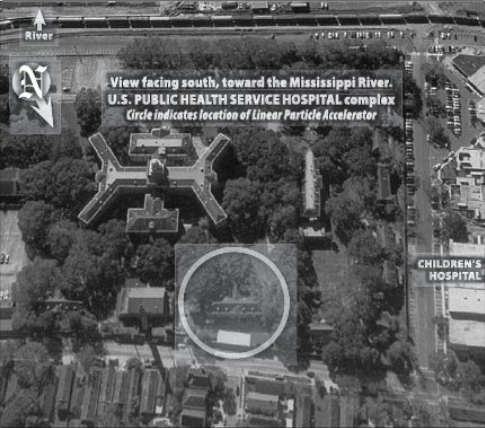

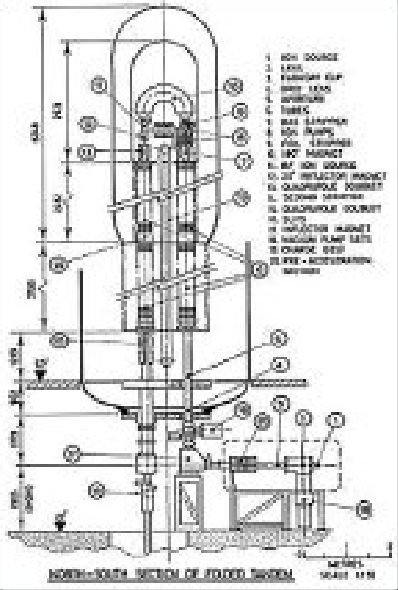

Readers of Haslam’s previous book, Mary, Ferrie & the Monkey Virus, will recall the author’s suspicion that Dr. Sherman’s death may have been the result of an accident involving a linear particle accelerator used in the cancer research. In this updated account, Haslam lays out strong evidence that just such a device was in use on the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital grounds near Tulane in the 1960s.

His previous work was embraced by the late Mary Ferrell, that indefatigable Dallas JFK assassination researcher. When asked her opinion of Haslam’s research, Mary replied, “Based on what we know today, I think it’s totally accurate.”

In this new volume, Haslam brings the one thing missing from his earlier work — a living witness.

The importance of this new testimony was summed up by consummate conspiracy debunker John McAdams, who stated, “If Judyth Vary Baker is telling the truth, it will change the way we think about the Kennedy assassination.”

Ed Haslam’s research may indeed change the way we think about the assassination, about Lee Harvey Oswald and about the greatest health scandal in history.

The tragic assassination of President John F. Kennedy may come to be seen as a mere bump in the road of a series of national scandals and conspiracies which have plagued the United States right up to today.

JIM MARRS, SPRING 2007

ON ONE LEVEL THIS BOOK is a cold-case investigation into the 1964 murder of Dr. Mary Sherman in New Orleans — a murder which remains unsolved and is remembered as one of the most mysterious ever committed in a city that has known so much mystery and so many murders. But there is more to this story than murder and mystery.

Understanding the death of this one woman unravels much of our nation’s secret history. It illuminates the darkness. It connects great medical disasters of our time to important political events of the day. It unveils the contamination of hundreds of millions of doses of the polio vaccine with dozens of monkey viruses. It spotlights the epidemic of soft tissue cancers that swept our country. And it exposes dangerous secret experiments which used radiation to mutate cancer-causing monkey viruses. It connects leaders of American medicine to the accused assassin of the President of the United States. This one murder helps us understand why we have been lied to with such conviction for so many years — and why those lies are likely to continue.

But this is not a murder mystery: fascinating perhaps, but hardly entertainment. For me, writing this book was difficult, stressful and dangerous. What began as an investigation into this single murder morphed into consideration of epidemics which killed millions of people and which cost billions of dollars. It became an investigation into an underground medical laboratory that was accidentally discovered during an investigation into the JFK assassination — a laboratory which secretly irradiated cancer-causing monkey viruses to develop a biological weapon.

This story seems to have followed me throughout my life, and its recurring pattern is eerie indeed. Had I realized its importance, I would have paid closer attention. What I do remember are fragments that I pieced together later in life: a name here, an incident there, pieces of a puzzle often separated by years of unrelated distractions. I even remember sitting on Mary Sherman’s lap once as a child. She and my father worked together at Tulane Medical School in New Orleans. They had taken a British doctor out to dinner and then to our family’s home for an after-dinner drink.

When she died in the summer of 1964, I saw my father cry for the first time. As a Navy doctor during World War II, my father had seen more than his share of burned and broken bodies. Someone (I don’t know who) had asked him to go to the morgue to look at Mary Sherman’s body to get a second opinion on her unusual death. He came home from the morgue that day, fixed himself a drink, sat down in his chair, and cried silently. I wondered what was wrong. My mother told me that a woman he knew from the office had died. It was only later that I learned it was Mary Sherman.

Seeing my father cry was memorable for me — a once in a lifetime experience. Having spent his career amputating limbs and standing in an Emergency Room making life-or-death decisions about people pulled from mangled vehicles, he was not prone to show much emotion. I mention this incident here because it is important to our story. It is how I learned about the evidence that unraveled the mystery of Mary Sherman’s murder. My father told my mother, and my mother later told me: Mary Sherman’s right arm was missing.

This key fact in the case was never told to the press. Why not? Can you imagine the O.J. Simpson trial without “the glove”? Why was the press not told the most obvious fact in this case? Who was trying to protect whom? Were there powerful forces controlling the story from the beginning? If so, what did they not want us to know? And why did they not want us to know it?

That same summer, I overheard my father complain bitterly when he learned about certain activities going on at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital. His anger and frustration seemed out of character for this deep-keeled man. I remember his words: “We fought wars to keep people from doing things like this.”

IN THE SUMMER OF 1964 my father learned something about what had been going on at the USPHS hospital. I do not recall if this was before or after Mary Sherman’s death, but it was around that time. He was particularly insulted by the idea that it was taking place on the grounds of the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital, a facility that was supposed to protect the American public from deadly diseases.

When he vented his frustration to my mother, she reminded him that there was probably nothing he could do about it “at this point.” His response: “It's just that I gave up so much to keep stuff like this from happening.” I have always understood this comment to be about leaving the Navy and ending his admiral-track career. Despite this high price, he remained dedicated to the idea of medical ethics, a commitment he acquired from his father — a bio-chemist, veterinarian, and medical doctor who helped develop the first anthrax vaccine. Thus he was not only not a part of these secret radiation experiments, but was also disturbed to learn about them.

In the late 1960s, I heard about Mary Sherman’s connection to an underground medical laboratory run by a suspect in the murder of President Kennedy. I was told they were using monkey viruses to create cancer. The possibility of this being used as a biological weapon was clear. The dark specter of unleashing a designer virus on the world haunted me. I even offered a sarcastic comment at the time: “The good news is if there’s a bizarre global epidemic involving cancer and a monkey virus thirty years from now, at least we’ll know where it came from.”

IN 1971, during what might be described as a deathbed conversation, I confronted my father about Mary Sherman. He was getting ready to go to the hospital. For the first time in his life, he was going as a patient. His cancerous lung was scheduled to be surgically removed in the morning. We both knew that, due to his fragile health, he would probably not survive the surgery. We discussed it. We both realized that this would probably be the last conversation we would ever have with each other. He stoically gave me instructions about caring for my mother. I listened and pondered the strength of this quiet man who had seen so much death in his professional life. I studied the courage with which he faced his own.

When he finished, I acknowledged his requests and confirmed my willingness to carry out his instructions. Then I said that I had a few questions of my own. Questions that I would never be able to ask him again. Questions that I thought were important for him to answer, so that the truth would not die with him. I asked him to tell me about Mary Sherman and about all that spooky stuff that was going on at the U.S. Public Health Service Hospital. “Wasn’t she some kind of cancer expert?” I ventured.

He shook his head slowly from side to side, to let me know that he would not tell me.

I persisted. I wanted to know why he would not tell me. Solemnly he said, “There might be repercussions. I have to think about the family first. I have to protect them.”

“What if I figure it out myself?” I challenged. “I’m hardly in a position to stop you,” he said with the casual resignation of a man who never expected to see another football game. Then he collected his thoughts and, in a grave voice, he gave me this warning: “Ed, I need you to listen to me carefully. I will not be able to say this to you again. If you do figure out what happened down there and decide to tell the world what you found, I need you to realize that you will be crossing swords with the most powerful people in our country. And you should think twice before crossing them.”

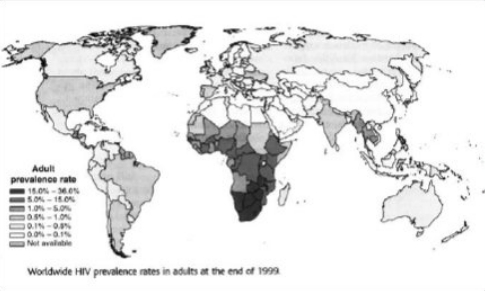

THE 1980S USHERED IN THE EPIDEMICS that I had feared in the 1960s. The mainstream scientific community stated that AIDS was caused by the unexplained mutation of a monkey virus. They estimated the date of the mutation to be around 1960. The logical question (who had been mutating monkey viruses around 1960) was not even asked in the press. And, yes, I was concerned about what I had heard in New Orleans. It all sounded so similar. Could there be a connection? And if there was, was there any point in speaking up about it? Trade places with me for a moment: If you were in my shoes, would you have?

I went to medical libraries and read scientific articles hoping to find facts that would make my fears unfounded. I was anxious to find a flaw in my own argument, which would enable me to walk away from a project that was starting to consume all of my free time. I did not find the flaw, but I did find something else.

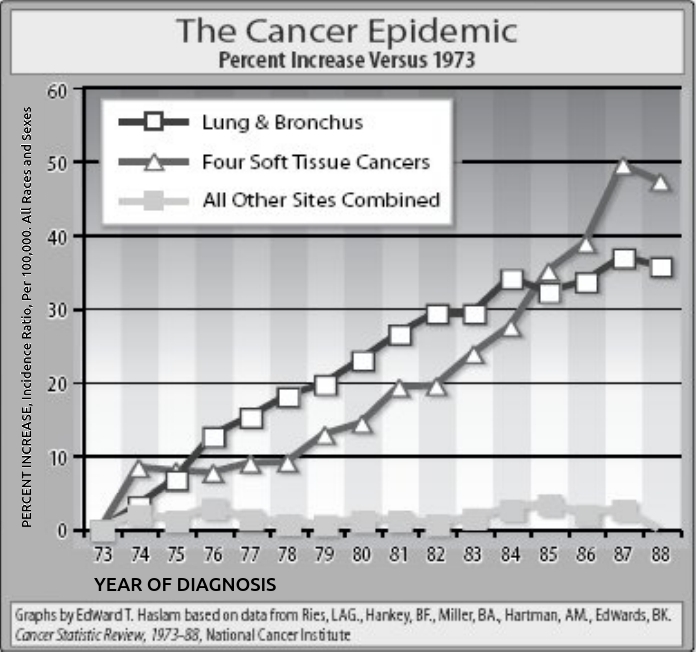

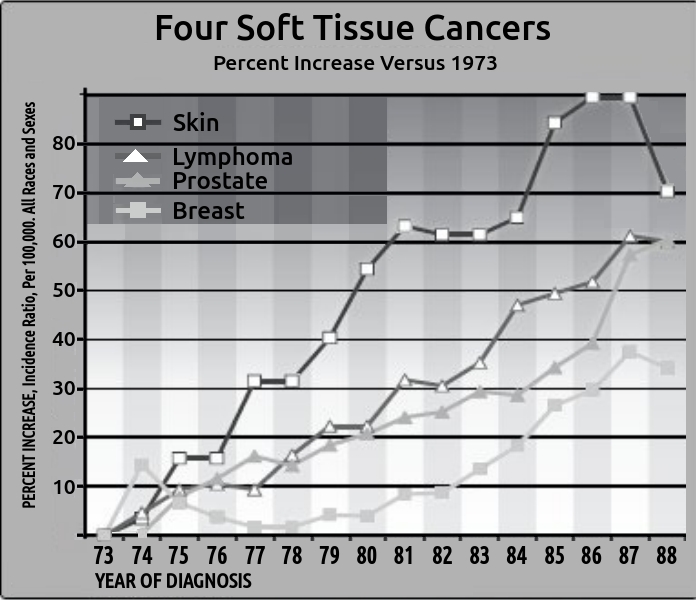

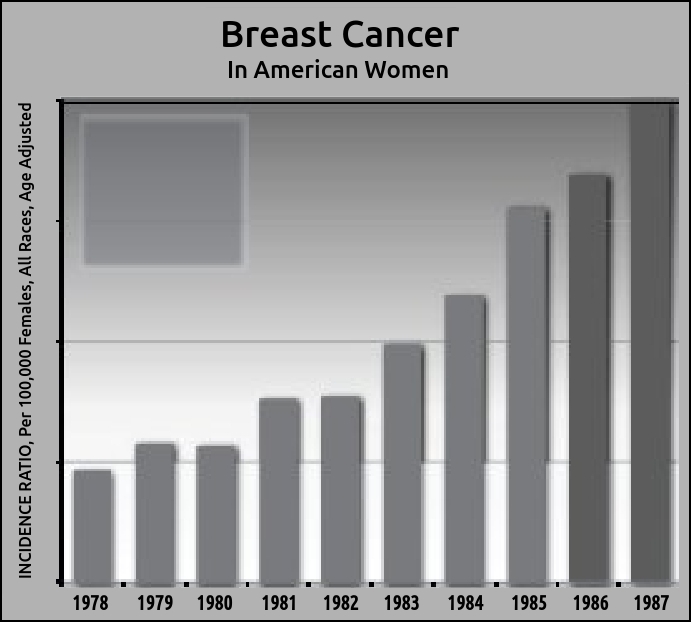

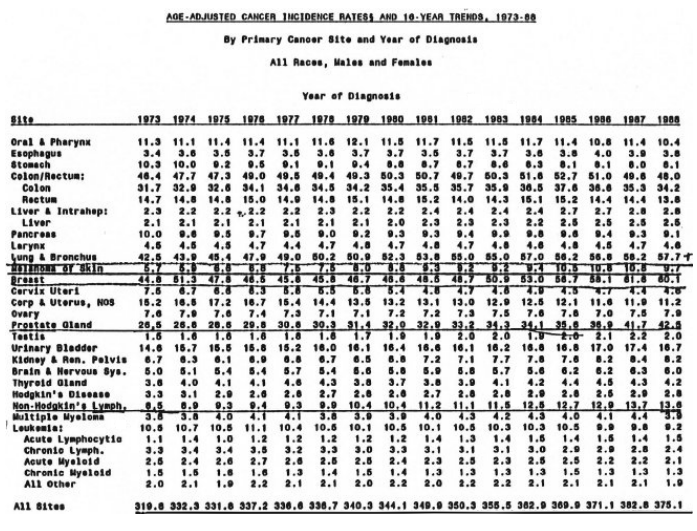

As I poured over the official cancer statistics from the National Cancer Institute, I saw the dimensions of the massive epidemic of soft-tissue cancers that had swept our country. An epidemic that had been all but ignored by our watchdog press. An epidemic that could reasonably be explained by the cancer-causing monkey viruses that had contaminated the polio vaccine of my youth. Whatever I felt my options were prior to that moment, they suddenly narrowed.

I also noticed that names connected to the polio vaccine were names connected to Mary Sherman and to the investigation of the JFK assassination. I began to suspect that these secrets were somehow intertwined. A web of secrecy surrounding our national health. Interlocking secrets that protected each other. Secrets which presented serious accountability problems for the people in power. I remembered the warning my father had given me. I could see how unwelcome this news would be in many circles.

IN THE 1990S I FOUND DOCUMENTATION and witnesses to support much of what I had heard as a child. My fears were now based in facts. I met highly-credentialed scientists who understood both the history and the science behind these events clearly, and they took my concerns seriously. Some quietly helped me find people who knew things that I needed to know. They helped me connect the dots.

Finally, I found evidence of the radioactive machine used to mutate the monkey viruses. I now had motive, opportunity and what detectives call propinquity (right people, right place, right time). I decided it was time to speak out — even if I did not have all the information in hand at the moment.

In July 1995 I self-published my story as Mary, Ferrie & the Monkey Virus: The Story of an Underground Medical Laboratory. I could only afford to print 1,000 copies, but I hoped that getting the story out might attract a publisher. After the first thousand books were gone, I could not afford a reprint. Still without a publisher, I switched tactics and started photocopying comb-bound manuscripts in batches of ten. This new technique enabled me to update the book with new information as I found it and kept me in print for years. A handful of orders trickled in each week. By the end of 1999, a second thousand books had been shipped. With copies in all fifty states and five foreign countries, I felt that “the cat” was now “out of the bag,” and I could finally go back to my advertising career and try to make a living — which I did in 2000.

It was at this exquisitely inconvenient moment that 60 Minutes, the CBS News TV show, contacted me. They were investigating a woman who said that she had been in the underground medical laboratory that I had written about in my book. That she knew Mary Sherman. That she had been trained to handle cancer-causing viruses. That she had been part of the effort to develop a biological weapon. That she knew Lee Harvey Oswald. Would I meet with them for an off-camera interview? I accepted.

By the time 60 Minutes interviewed me in November 2000, they had already interviewed their witness for hours. They got additional input from other researchers and journalists. Finally, they decided not to air her story.

Three years later, in November 2003, the History Channel aired a story about this same underground medical laboratory. It mentioned Dr. Mary Sherman, David Ferrie, and Lee Oswald, but not my book. The episode, featuring a young woman who had handled the cancer-causing monkey viruses for the secret project, was part of their series The Men Who Killed Kennedy. A week later the History Channel reversed course. The episode was withdrawn from circulation, and has not been aired again.

OUR STORY COMES FROM A FERMENTING MASH of science, secrecy, patriotism, power, paranoia and extremism. It is not a pretty picture. It involves death, disease, covert wars, and the quiet hand of power. In our path sit innocent people whom I am sure would prefer not to be involved. I apologize to them in advance. Then there are others who claim to have forgotten everything they know about this matter or who know but refuse to talk. To them I offer no apology.

This story casts a shadow that is so dark and so long that I have chosen to tell it simply. Some have said that it has the nightmarish quality of an anxiety dream. I prefer to see it in a different light. It is, as songwriter Jackson Browne once said, “the fitful dream of some greater awakening.” We are just beginning to wake up to the responsibilities of being a free society. It is much more complicated than dropping bombs on an obvious enemy. It is time we began to question what the people of power did with the trust and money we gave them.

I doubt we will ever hear the Surgeon General stand up at a press conference and acknowledge this operation. This one still possesses serious accountability problems for those who hold positions of power. Further, it comes from the land of unvouchered expenditures, where the trails of accountability were obscured by professionals decades ago.

There are reasons for such secrecy. Powerful reasons. Reasons capable of destroying careers and toppling governments. A full exposure here would threaten the treasure of our nation’s wealthiest corporations, the reputations of some of the powerful political figures of the day, and the precious confidence we give our national institutions. While we can understand why they kept these matters secret, we have a different goal.

Our task is to unmask these secrets because they were hidden from us for reasons. Powerful reasons. Reasons that affect decisions being made today. Reasons that involve politics and medicine. Reasons that affect our health and ultimately our freedom.

To investigate such secrecy is a formidable task. We tread lightly for we walk upon tender ground, over the bones of children, through sour rooms of tumor-bearing mice, and into the blood-stained bedroom of one of our nation’s most respected cancer researchers. It is here we search for knowledge that was not meant to be known. We will use published sources and official records as best we can. At times we examine these more closely and in greater detail than anyone before us. But we must be prepared to look beyond the official paper trail and to use less certain methods to find our way. Methods like oral history, personal testimony, feeble press accounts, censored government documents, and our own capable and curious intellects.

|

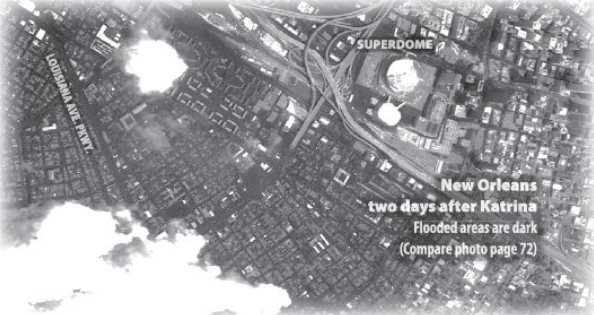

Complicating our task further is the catastrophic flood of 2005 that followed Hurricane Katrina. Irreplaceable documents (like the crime-scene photos) and precious physical evidence (like the blood-soaked gloves found in Mary Sherman’s apartment, which could still yield DNA or other clues) may have been lost forever when the waters of Lake Pontchartrain engulfed the city of New Orleans. Yet we can proceed with what we do know. As you will see, plenty of evidence had been collected previously.

You will find this book as much of a personal odyssey as a journalistic work. But that’s what happens when you investigate a murder only to discover an epidemic. Either way the destination is the same. I will tell you why I am deeply suspicious of certain activities that occurred in New Orleans in the 1960s, and why you should be too. We will begin with what I personally saw and heard over the years. To that we add years of research.

Then we get questions. Fair and honorable questions. Questions which deserve answers. Questions which have their own purpose, their own energy, even their own dignity. Questions which will eventually help us coax this Orwellian monster out of its swamp of secrecy.

EDWARD T. HASLAM, SPRING 2007

DR. MARY’s MONKEY: HOW THE UNSOLVED MURDER OF A DOCTOR, A SECRET LABORATORY IN NEW ORLEANS AND CANCER-CAUSING MONKEY VIRUSES ARE LINKED TO LEE HARVEY OSWALD, THE JFK ASSASSINATION AND EMERGING GLOBAL EPIDEMICS

Copyright © 2007 Edward T. Haslam. All rights reserved.

Book layout and cover by Ed Bishop

TrineDay

PO Box 577

Walterville, OR 97489

1-800-556-2012

www.TrineDay.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2006911309

Haslam, Edward T.

Dr. Mary’s Monkey: How the Unsolved Murder of a Doctor, a Secret Laboratory in New Orleans and Cancer-Causing Monkey Viruses are Linked to Lee Harvey Oswald, the JFK Assassination and Emerging Global Epidemics / Edward T. Haslam; with forward by Jim Marrs — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Epub ISBN 978-1-936296-65-1

Mobi ISBN 978-1-936296-66-8

Print ISBN 978-0-9777953-0-6 (acid-free paper)

1. Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 1917-1963—Assassination. 2. Oswald, Lee Harvey. 3. Poliomyelitis vaccine—Contamination—History—Popular works. 4. Political Corruption—United States. 1. Title 364.1’524—dc20

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5

Printed in the USA

Distribution to the Trade by:

Independent Publishers Group (IPG)

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

312.337.0747

www.ipgbook.com

|

|

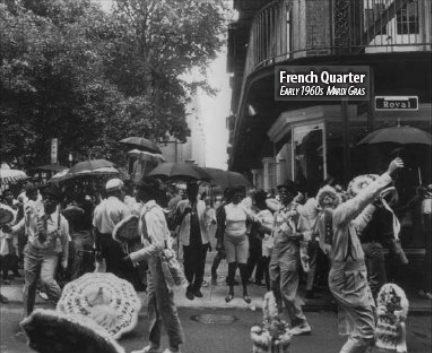

IN THE SPRING OF 1962 I WAS A CHILD OF TEN YEARS. Those innocent, sun-filled days were spent swimming and sailing on Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans.

This particular day, my father and I had been sailing on his boat, the Interlude, a modest double-ended wooden sloop whose leaky hull showed its age. The Interlude was a noticeable step down the status ladder from the larger, newer, more glamorous boats which flanked it on the pier. Boats tend to be metaphors of their owners, and this was no exception. It was an unpretentious boat for an unpretentious man.

My father was dressed in his habitual sailing clothes, baggy khaki pants, a blue cotton shirt, and a dark blue baseball cap that covered his short-cropped head of completely grey hair. This attire was as close as he could get to his old Navy uniform, and he wore it whenever he sailed. With his omnipresent cigarette in hand, he shuffled down the concrete pier in a casual gait with me at his side. This quiet man honored simplicity and enjoyed the peace that followed a long, terrible war.

This rumpled façade concealed a complex and accomplished man who had witnessed more than his share of human suffering. The son of a country doctor, he graduated from Harvard Medical School in the late 1930s and then served as an officer in the U.S. Navy, in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, during World War II. By the end of the war, he was planning medical support for an invasion of Japan, where they anticipated one million American casualties. In 1946-47, he was stationed (with his wife and infant daughter) in the smoldering Philippines. Upon returning to the states, he left the Navy and specialized in orthopedic surgery. After several moves, he settled in New Orleans in 1952. Now he made his living teaching at Tulane Medical School, performing surgery, and working with crippled children. He sailed to relax.1

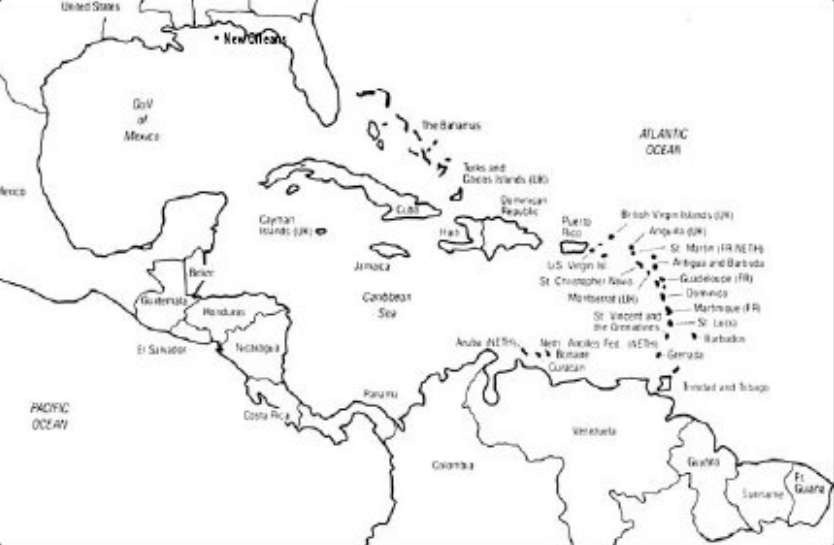

As we walked, we approached a section of the pier referred to as the Visitor’s Dock, where sailors from around the world occasionally stopped on their travels. Since New Orleans was the northern port of the Gulf of Mexico, salty boats and weathered crews frequently came straight from the Caribbean and Central America. Some of these boats were remarkably picturesque, more reminiscent of ships from “the great age of sail” than the sleek modern designs which populated yacht club harbors. This day, an exceptionally nautical-looking boat had slipped into the Visitor’s Dock while we were out sailing.

“Look, Dad! It’s a pirate ship,” I said with great excitement. The boat was a gaff-rigged schooner about fifty feet long with a carved wooden figurehead on the bow. A live parrot was perched on a cross beam in the rigging. Freshly-washed clothes were hung out to dry.

|

“And there’s the pirate,” I whispered, letting my wide eyes announce the importance of the news. Coming down the pier towards us was the boat’s skipper, a bare-chested barefoot gypsy, looking every bit like the Ancient Mariner himself. Never before had I seen such a character in person. His leathery skin held a deep brown tan set off sharply by his tattered sun-bleached pants cut below the knee. Long curls of grey hair haphazardly fell from under the bandanna tied around his head. On his shoulder sat a small, mischievous monkey about twelve inches tall, tethered on a leash. As we passed, the pirate smiled at us; his eyes sparkled. The monkey studied us with his small round head and big brown eyes. Despite my intrigue, I gave them a wide berth and tried not to stare, but it was difficult. My thoughts were now focused on the monkey.

I had seen plenty of monkeys before, mostly in the zoo, but I had never thought about having a monkey as a pet. We had a dog. Why not a monkey? It would be much more interesting. So I asked my father, “Dad, can I get a monkey for a pet?”

“No,” was his immediate answer. After a pause, he anticipated my next question by adding, “They carry diseases.”

I had heard my mother mention that monkeys occasionally carried rabies. I reasoned to myself for a moment: Dogs could carry rabies, but we had a dog. A vet could tell you if your dog carried rabies, so a vet should be able to tell you if your monkey carried rabies. And nothing (to my ten-year-old mind) could possibly be worse than rabies! I decided to give the monkey pet idea a second try. “Like rabies?” I countered.

“Yes,” he answered in a fat tone. “They can carry rabies, but they carry a lot of other diseases, too. Some are weird viruses that we don’t understand yet. Some of them can kill you.”

I was puzzled by his comment. I wondered how my father, an orthopedic surgeon whom the children in my family jokingly referred to as “old sawbones,” knew about weird monkey viruses which were still being researched at the leading edge of medical science. So I asked him, “Where did you learn about that?” He paused to take a long drag off his cigarette and seemed to be thinking about the question. In the interim I decided to speculate: “Did you learn about that in the Philippines?”

“No,” he said, blowing out his cigarette smoke in a short breath. “I don’t suppose there’s any harm in telling my ten-year-old son” as if talking to a cloud. Then he turned to me and said, “They’re researching monkey viruses down at the med school. Some of the more deadly ones are coming in from Africa.”

Africa?!!! I may have been ten years old, but I did not need Joseph Conrad to tell me that Africa was mysterious. From what I had seen in school and on television, Africa was a wild, poverty-stricken continent riddled with starvation and horrifying diseases. It was also full of bizarre forms of life which defied your imagination, like ants the size of your foot and snakes as long as your car. I was not interested in catching any weird fatal virus from Africa, no matter how cute the monkey. I wondered if the pirate knew the danger he was in.

The fact that these diseases obviously concerned my father more than rabies made a huge impression upon me. His comments ended my desire for a pet monkey, but they were the beginning of my curiosity about the monkey virus research being conducted in New Orleans. My first real question arose from my dad’s cautiousness: Why were Tulane’s doctors not supposed to talk about the monkey virus research program?

1 My father was a limb surgeon whose specialties were reconstructive surgery and the rehabilitation of amputees. He was President of the Crippled Children’s Hospital and Medical Director of the Physical Rehabilitation Center at Delgado College. He knew Mary Sherman because they both taught orthopedic surgery at Tulane Medical School in the 1950s and early ‘60s. He never worked at Ochsner’s clinic or hospital. He was not a virus researcher and was not involved in the underground medical laboratory in any way.

SEVERAL DAYS AFTER THE PIRATE INCIDENT we had a substitute teacher at school. In the middle of the day she turned her attention to science and started talking about germs and diseases. She reviewed the basics about how germs caused diseases and how our bodies fought back. She went on to explain the differences among bacteria, fungi, and viruses. As her lecture continued, she confidently explained how modern medicine had triumphed over bacteria and fungi with medicines and antibiotics. Then she moved the discussion to the frontier of medicine, where researchers were battling the mysterious world of viruses.

I raised my hand to make a contribution to the discussion: They were researching viruses down at Tulane Medical School. (I knew the monkey subject was taboo, so I did not mention it.) “No,” she said immediately, and turning toward the entire class, she said, “That’s wrong,” in a definitive voice. “Tulane is just a college and its purpose is to teach students, not to do research. Virus research,” she continued, “is a very complex subject and is only done by very intelligent specialists at faraway places like Harvard and Johns Hopkins universities and at special government research centers which have special equipment.”

I was embarrassed by her response, but there was nothing I could do about it. I knew she was both right and wrong. Tulane’s faculty was full of people from Harvard and Hopkins. My father was one of them. Many of them were doing research. For over 100 years the reputation of Tulane had been based on battling tropical diseases like yellow fever and malaria.

It was true that the names Harvard and Johns Hopkins were in the news more often than Tulane, each time announcing some medical breakthrough or at least updating the public on their progress in fighting some dreaded disease. Other than announcing its pathetic football scores, Tulane’s name hardly ever appeared in the local press. Public news about Tulane Medical School was basically non-existent in the 1960s.2 The teacher had stated the public’s perception accurately enough. More importantly, I knew that nothing I could say would change her mind. More than likely she just could not grasp that idea that something “local” might be important. Beaten for the moment, I held my tongue.

2 Tulane did publish the Bulletin of the Tulane Medical School, but it was an industry relations piece sent to other medical schools.

THE NEXT TIME I HAD A CHANCE to talk to my father I asked him why it was that we always heard on the news about the medical research being done at faraway places like Harvard and Johns Hopkins, but we never heard about the research being conducted at Tulane.

“Not everybody wants publicity,” he patiently explained. “Yes, some people do research because they want to be famous and tell the world how great they are; but other people are not interested in publicity, and they do research to get information and knowledge. It’s just part of being involved in academic medicine.”

While I understood that he was trying to communicate the nobility of quiet scholarship, his answer did not make sense to me. Such an explanation might explain the bragging of an upstart school, but it did not explain why we heard about research from first-class schools like Harvard and Hopkins, but not Tulane. I thought about his comment for a minute and asked, “What sort of people wouldn’t want the public to know about their research?”

He hid his exasperation with my relentless questioning in his quiet bedside manner, and said that much of the research at Tulane was financed by money from drug companies and from the U.S. government. These grants were frequently for experiments with drugs that were not yet ready for the public. Therefore, there was no reason to tell the public about them.

That still did not answer the question to my satisfaction. Sooner or later those drugs would be ready, but somehow I knew we still would not hear about them. The not-ready-yet argument was as true for Harvard and Hopkins as for Tulane. But I did understand his main points clearly. First, Tulane did not have enough money to fund its own research and was dependent upon others, like drug companies and the U.S. government, who consequently dictated what was to be researched and what was to be talked about. And secondly, Tulane Medical School did not get publicity because it did not want publicity. While this was not much of a victory for me, at least I understood why the teacher and the public did not know about Tulane’s virus research programs.

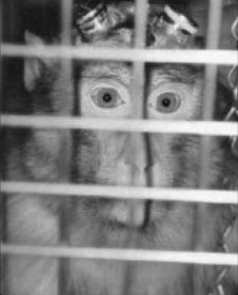

Actually there were some very good reasons to keep subjects like researching monkey viruses quiet. The main ones were (1) potential public panic over an accidental epidemic, (2) growing public pressure from the animal rights movement, and (3) the secrecy demanded by covert operations.

The possibility of public panic over an accidental epidemic was a real and present danger to both researchers and their financial backers. One bad incident might trigger a public outcry that would effectively shut down all such research for years. The possibility of such an accidental epidemic was very real, and the scientists knew it.3

|

During the early 1960s there were numerous outbreaks of infectious diseases among the animal handlers in monkey labs around the country.4 Waterborne diseases were transferred through saliva, moisture in the breath, and urine. They could be caught just by being around the primates. Cleaning out animal cages was dangerous. Feeding a monkey was dangerous. Taking a monkey out of a cage was dangerous. Holding a monkey was dangerous. Primates are intelligent mammals, and they quickly figured out that a trip with a handler often meant getting stuck with needles, or having the top of the skull chopped off with a power saw, or being injected with psychoactive drugs. The monkeys fought back. They bit their handlers. They urinated on them. They tried to escape. Monkey handlers who drew blood from one cancerous monkey to inject it into another occasionally stabbed themselves with needles full of blood laced with carcinogenic monkey viruses.5 The dangers were enormous, and the controls were feeble by today’s standards. The generality of all this is well documented in medical libraries around the country. One book published during the 1960s made the point clearly in its title, The Hazards of Handling Simians, and listed the numerous outbreaks of diseases in the primate research facilities during the previous two decades.6

Then, the monkey handlers would go home and resume their normal lives, including sexual activities. The potential for zoonoses (diseases jumping from animal to man) was very real, and the medical community knew it.

Consider these comments written in the 1960s by Richard Fiennes, Britain’s leading primate researcher, about the dangers of primate research:

There is … a serious danger that viruses from such closely related groups as the simian primates could show an altered pathogenesis in man, of which malignancy could be a feature. The dangers of such happening are enhanced by man’s exposure in crowded cities to oncogenic agents and increased radiation hazards …

The danger of transmitting simian viruses in vaccines is a real and alarming one …

The further danger is that simian viruses might become adapted to human populations, and spread with appalling rapidity, and under circumstances in which there were no possible immediate means of control …

Knowledge of prophylaxis against viral diseases is in its infancy, and time must elapse before any effective vaccine could be prepared, tested, and manufactured in bulk to protect populations against a pandemic caused by a new virus …

Plainly, it is in the realms of virology that primate zoonoses present the greatest danger …

Far too little is known of the virology of simians …7

Does this sound familiar? Does it not predict the current AIDS epidemic? Speaking further of this danger, Fiennes discussed O’nyong-nyong, a mildly lethal virus that swept Africa:

Had O’nyong-nyong been attended by a high death-rate… the human population of a large part of East and Central Africa would have virtually ceased to exist. To such an extent, in spite of twentieth-century medicine, is man still vulnerable to attack from new viruses.8

The danger was real. The fear of public panic was real. With experimental animals, unpredictable viruses and exposed animal handlers intermingled in a sweltering tropical city of nearly a million people (like New Orleans), the opportunity for a biological disaster was ripe.

The idea of an epidemic suddenly sweeping the streets of an American city was not foreign to the public. In fact, a movie called Panic in the Streets won the Academy Award for best screenplay in 1952. Panic in the Streets depicted a U.S. Public Health Service officer battling a modern day outbreak of bubonic plague on the streets of New Orleans. But the press of the 1950s and 1960s either did not consider the public’s interest in medical matters substantial enough to warrant coverage, or they felt they had a higher duty to prevent public panic. Either way, the press did a poor job of covering the issue then. But, they do a better job of covering it today.

For example, an accident occurred at a Yale laboratory in the 1990s. The headline in Time shouted, “A Deadly Virus Escapes.” The sub-headline continued, “Concerns about lab security arise as a mysterious disease from Brazil strikes a Yale researcher.”9 The researcher worked at a Biohazard-3 lab and was studying a rare, potentially lethal virus when he broke a test tube. He failed to report the incident, which sprayed this virus into his nostrils. Instead, he went to visit friends in Boston. When the incident was discovered, the researcher was quarantined, and his friends were put under medical surveillance. The article concluded, “If researchers do not tighten some of their procedures, the next outbreak might not be so benign.” All of which makes one wonder: What safety procedures were enforced in the monkey labs of the 1960s? And what procedures would have been followed in an underground medical laboratory with no visible sponsor?

3 An outbreak of infectious hepatitis was reported in New Orleans in 1962 by A. Riopelle and J.F. Molloy: “Infectious Hepatitis at Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology,” Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 1962, Vol. 1 (4), p. 12. See also Fiennes, Zoonoses of Primates as related to Human Disease (Cornell, 1965), p. 146.

4 Fiennes, Zoonoses of Primates, p. 142, plus Hazards of Handling Simians (International Association of Microbiological Associations, 1969).

5 Allison, A.C., “Simian Oncogenic Viruses,” Hazards of Handling Simians, p. 172.

6 Hazards of Handling Simians (International Association of Microbiological Associations, 1969), table.

7 Fiennes, Zoonoses of Primates, pp. 144-150.

8 Ibid., p. 149

9 Lemonick, Michael D., “A Deadly Virus Escapes,” Time magazine, September 5, 1994, p. 63.

To understand the type and extent of monkey virus research being done in medical schools in the 1950s and 1960s, I went to medical libraries and started reading the history of virology. While even an overview of these activities is beyond our scope at the moment, there are a few points worth mentioning. First is that it was well established in these medical research circles around the world prior to 1960 that certain monkey viruses caused various types of cancer, including cancers of the skin, lungs, and bones.10

Secondly, experimentation with carcinogenic viruses was widespread throughout the network of primate research centers, from the U.S., to Europe, to the U.S.S.R. Blood, tumor cells, and viral extracts were routinely taken from a variety of animals and injected into monkeys like a game of viral roulette. One lab created tumors in as little as eight days.11 Another lab injected human volunteers with the known cancer-causing monkey viruses to observe the effects.12

New diseases started to appear — diseases which were unknown in the wild. One such disease that first appeared in the lab is now called SAIDS or Simian AIDS.13 It occurred when African monkey viruses were given to Asian monkeys. SIV, the retrovirus that collapsed the immune systems of Asian monkeys, did not cause disease in its natural host, the African Green monkey.14

In addition to viral roulette, researchers experimented with radiation therapy, beaming x-rays and gamma rays directly into tumors to encourage remission. The medical researchers of the 1960s irradiated tumors in laboratory animals, including primates, and shot radiation directly into the tumors of human patients.15 Think this one through before we proceed. When you shoot a radioactive beam at a tumor, you not only hit the tumor, but you also hit the blood and viruses in and around the tumor. Was the type of radiation used to dissolve cancer tumors strong enough and focused enough to damage the DNA and RNA of the viruses floating in the patient’s blood?

At this point, the medically sophisticated reader might say, “Wait a minute! The radiation exposure of a clinical x-ray machine does minimal damage to DNA or RNA, and very many people receive very many x-rays without getting cancer.” And this is true where we are talking about the exposure and energy levels associated with common clinical use, which have been clinically established as relatively safe for humans.

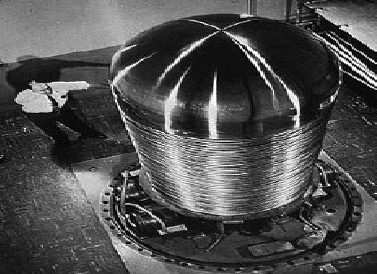

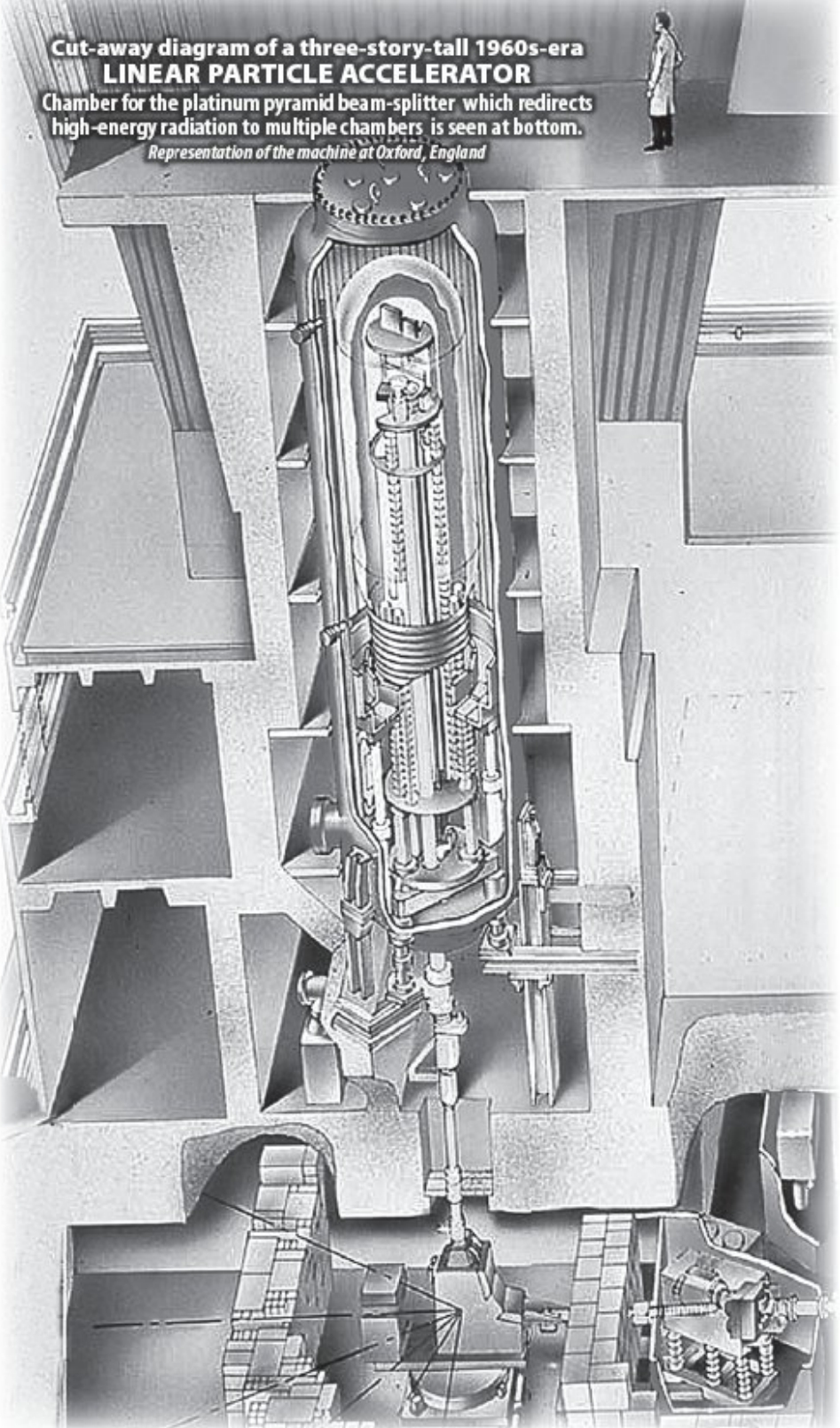

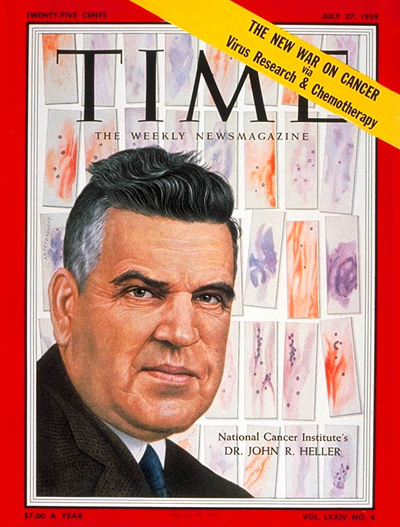

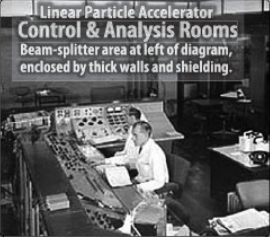

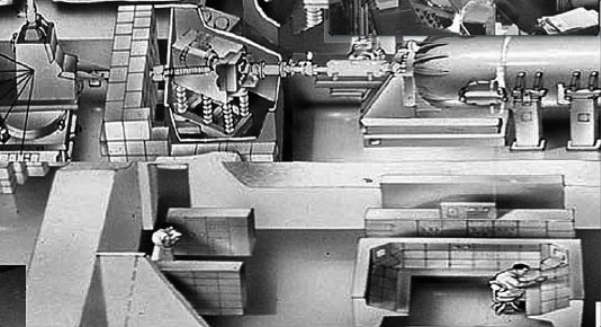

However, in the late 1950s a powerful new device emerged from the physics lab and quietly began to be distributed to selected medical research facilities. It was called a linear particle accelerator.16 Never before had a machine of this magnitude been put into the commercial workplace. You might think of it as a poor-man’s atom-smasher. These high-voltage scientific machines were capable of doing things never done before, and they spawned new ultra-hi-tech applications that stretched the imagination. Their basic capabilities included producing high-energy radiation and hurling sub-atomic particles near the speed of light into whatever object one desired.17 To illustrate their ability to change things generally considered to be unchangeable, let’s look at a commercial application of a linear accelerator in South Africa. Shooting subatomic particles through imperfect yellow diamonds stripped the impurities out of the yellow diamonds and turned them into clear marketable white diamonds. These linear accelerators were capable of destroying anything in their path. There is nothing they could not cut, if directed to do so.

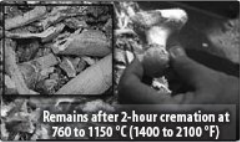

This particular point was dramatically demonstrated by a man named Jack Nygard, an engineer at a company in Boston which manufactured linear accelerators.18 Nygard developed ingenious new commercial applications for linear accelerators, from preserving bananas to cross-bonding wood. By shooting particles laterally through plastic-laminated wood, Nygard created a new structural matrix inside the wood. The result was an ultra-hard super-wood that would never warp. It was the perfect low-maintenance solution for the bowling industry. Nygard turned entrepreneur and set up shop in the heart of the lumber industry near Seattle, Washington, where he began producing his super-wood on a commercial scale. His success continued until the day the technician running his accelerator did not notice that Jack had stepped into the wood-processing area. When the technician flipped the switch on the 5,000,000 volt machine, it was the last anyone ever saw of Jack Nygard.19 The beam of electro-magnetic radiation burned him to the point of disintegration. They swept up his ashes. (Or so the story goes.)

The medical applications of linear particle accelerators included destroying cancer tissue and conducting various types of viral and genetic research. These machines were quite capable of either killing viruses or simply mangling the molecules in the genome necessary for reproduction.

In the field of virus research, radioactive medical experiments greatly increased the danger of an already dangerous scenario. They introduced the capability of mutating viruses already known to be deadly, and raised the possibility of creating both new vaccines and new super-diseases.

Some of the scientists involved in the field of monkey virus experiments got extremely nervous about the dangers of such experiments, and warned their colleagues in the mid-1960s that if one of these monkey viruses mutated into a more lethal form and got into the human blood supply, there could be a global epidemic which would be unstoppable, given the current level of medical knowledge!20

----------------------------  |

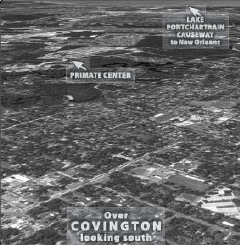

In 1959, the U.S. Congress finally took the danger of an accidental monkey virus epidemic seriously, and financed seven regional primate centers in order to get the experiments out of the cities.21

In Louisiana, the Delta Regional Primate Center opened its doors in November 1964 with Tulane University serving as the host institution.22 This took the monkey virus research out of downtown New Orleans and put it in 500 wooded acres near Covington, Louisiana, across Lake Pontchartrain. Today that laboratory has over 4,000 primates, thirty scientists, and 130 support workers, plus a public relations director whose job it is to boast of the center’s virus research, especially on AIDS, and to point to the improvements in lab security, such as the high-security zone, where researchers and staff shower and change clothes before approaching or leaving the 500 monkeys infected with simian AIDS. Despite these security measures, Delta was back in the headlines in 1994, when eighty-three monkeys escaped. The public was told to call Delta to report any monkeys seen swinging through the trees,23 the center having claimed the week before that nearly all of them had been captured.24

The Delta primate lab’s $4,000,000 per year operating budget comes directly from the U.S. government’s National Institutes of Health, as it has for the past forty years. One critic of animal research, Dr. Peggy Carlson of the Physicians’ Committee for Responsible Medicine, claimed that animal research is big business, and said, “They are taking money away from other areas and dumping it into a sinkhole.”25 Other critics opposed animal research on humanitarian grounds, many believing that animal research actually contributes more to advancing professional careers than to advancing human medicine.

A case in point involved ten monkeys, which were transferred to the Delta Regional Primate Center from Silver Springs laboratory after their infamous experiments triggered a national animal-rights debate in the 1980s. Delta terminated eight of the monkeys following heavy-handed experiments. The other two monkeys which had their spinal cords deliberately severed at Silver Springs in the mid-1980s were kept alive at the Delta Regional Primate Center until the early-1990s.26

Dana Dorson, an activist from a group called Legislation in Support of Animals, saw little improvement in the new experimental oversight procedures: “Those committees just rubber stamp whatever is presented to them.”27 Attempting to counter the animal rights critics, Delta Regional Primate Center’s director Peter Gerone said, “Sometimes the public perception is that we do anything we want to monkeys, but that’s a myth. Maybe it was like that thirty years ago, but it’s not like that now.”28

OK, so just what was it like then? Gerone surely knew. A virologist, Gerone had been director of the Delta Primate Center for twenty-three years before making that statement in 1994. Appointed in 1971, he had left the U.S. Army’s Biological Warfare Center at Fort Detrick, where he had been one of their experts on airborne transmission of diseases.29 In 1975 he collaborated with representatives of the Defense Nuclear Agency, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases to attend an NCI-sponsored symposium on “Biohazards and Zoonotic Problems of Primate Procurement, Quarantine, and Research.” There he presented his paper on “Biohazards of Experimentally Infected Primates.”30

| Footnotes

10 Petrov, a Soviet scientist, used viruses to produce bone cancer in monkeys in 1951: Lapin, B.A., et al., “Use of Non-Human Primates in Medical Research, Especially in the Study of Cardiovascular Pathology and Oncology,” Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy, U.S.S.R., in Some Recent Developments in Comparative Medicine (London: 1966), ed. Richard Fiennes, p. 204. In the U.S., in 1957, Stewart and Eddy discovered “polyoma,” a virus that caused a variety of cancers in various animals; reported in Edward Shorter, The Health Century (New York, 1987), p. 198. By 1959, polyoma was considered to be essentially the same as SV-40, a monkey virus that caused various cancers in a variety of animals: Ibid., p. 201. 11 Lapin, “The Use of Non-Human Primates…,” Some Recent Developments in Comparative Medicine, ed. Fiennes, p. 206; also Spencer Munroe, “Viral Oncogenesis in the Rhesus Monkey,” Ibid., p. 229; also J.S. Munroe & W.F. Windle, “Tumors induced in Primates by a Chicken Sarcoma Virus,” Science (1963), vol. 140, p. 1415. 12 Grace, J. T. Jr. & E. A. Mirand, “Human Susceptibility to a Simian Tumor Virus,” Annals of the N.Y. Academy of Science (1963), vol. 108, p.1123. 13 Essex, Max & Phyllis J. Kanki, “The Origins of the AIDS Virus,” Science of AIDS: A Scientific American Reader (New York, 1989), p. 30. 14 Ibid., p. 32. 15 Three references to the use of radiation on tumors can be found in Tumors of Bone and Soft Tissue (Chicago: 1964). In “Histogenesis of Bone Tumors,” p. 16, Mary Sherman discusses genetic damage inflicted on cells by irradiation. In “Giant Cell Tumor of Bone,” p. 166, Sherman questions the claim that x-ray therapy turns benign tumors into deadly sarcomas. On p. 10 R. Lee Clark says, “X-ray therapy in the management of soft tissue of tumors is almost limited to Kaposi’s sarcoma.” 16 “The New War on Cancer via Virus Research and Chemotherapy,” Time, July 27, 1959, p. 54. 17 Dr. John Roberts, surgeon and president of the Medical Legal Foundation, interviewed by author, October 3, 1994. Roberts was one of the doctors who used linear particle accelerators to destroy cancer tissue, preferring it to Cobalt-60 because it could be controlled more precisely, minimizing destruction of healthy tissue. 18 Roberts interview. 19 Roberts interview. 20 Fiennes, Zoonoses of Primates, p. 149. 21 Eyestone, Willard H., “Scientific and Administrative Concepts Behind the Establishment of the U.S. Primate Centers,” Some Recent Developments in Comparative Medicine, ed. Fiennes, p. 2. 22 Ibid., p. 6. 23 Willits, Stacy, “Escapees Swinging Through Trees,” Times-Picayune/States-Item (New Orleans), September 1, 1994, Metro News 24 Willits, Stacy, “Primate Center Back in Spotlight,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), September 8, 1994, p. B-1. 25 Ibid.,” p. B-2. 26 Guillermo, Kathy Snow, Monkey Business (Washington, 1993). This book chronicles the decade-long battle between two tenacious whistleblowers and the federal government over extreme animal cruelty in the name of science. The level of animal cruelty described in this book can only be described with words like “mutilation” and “torture.” Criminal charges resulted. In the process, the whistleblowers founded PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and took their battle to both the U.S. Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court ruled in their favor, but not soon enough to save 60% of the monkeys from further experimentation and death. Scientific experimentation on monkeys continues today and is financed annually by $20,000,000 of U.S. taxpayer dollars. 27 Willits, “Escapees Swinging Through Trees.” Times-Picayune (New Orleans) September 1, 1994, Metro News 28 Willits, “Primate Center Back in Spotlight.” Times-Picayune (New Orleans) September 8, 1994, p. B-1 29 Guillermo, Monkey Business, p. 173. 30 Richard Hatch, “Cancer Warfare,” Covert Action, Winter 1991-92, p.18. |

I CAN SAY FROM PERSONAL EXPERIENCE THAT despite the establishment of the Delta Regional Primate Center in 1964, other primate research continued at Tulane Medical School in downtown New Orleans for years to come.

----------------------------  |

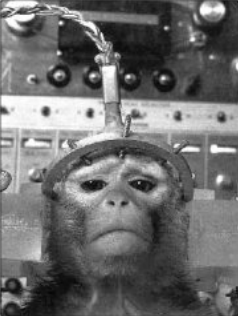

One day in the spring of 1970 I had gone down to the Tulane Medical School to help my father with a clerical project. After several hours I took a break and, as a distraction, set out to explore the mysteries of the medical school. Near the elevator on one floor, I found an incredible display of mutated human fetuses stored in glass jars. This mind-boggling collection of genetic malfunctions featured two-headed babies, Mongoloid fetuses, and Siamese twins. I decided to explore the other floors to see what else they had.

At the end of one hall I found an open door and a room full of cages. Inside there were monkeys. Each appeared to be wearing a flat-topped organ grinder’s hat. But a closer look revealed these were not hats.

A voice came from inside the room. “Come in. Come in. Who are you? And what can I do for you?” A professor sat in his chair looking at me, his head cocked to one side. He was dressed casually, a plaid shirt, no coat, no tie, no medical jacket. I introduced myself saying that I was visiting my father who was a professor in orthopedics. He invited me to come in and see the monkeys. He explained that the tops of their skulls had been removed with a bone saw and electrodes had been placed deep inside their brains. He held a sample electrode up for me to see.

It was a copper wire with a silver ball on the end which acted like a microphone inside the monkey’s brain, sensing and amplifying electrical signals. Once fifteen or so of these electrodes were implanted in the monkey’s brain, they were soldered to a data plug which was then glued to the monkey’s skull. Once everything was in place, the monkeys would be plugged into a electronic data-collection machine, similar to an EEG, and then injected with experimental psychoactive drugs. The machine measured the reaction of the various parts of their brains to the drugs. The professor held up a haphazardly folded scroll of paper full of squiggly lines to show me how the raw data was collected. “It’s amazing work,” I commented gesturing to the monkeys.

“Putting in the plugs is nothing,” he said in a tone that could only be described as arrogant. “The technicians do that. The hard part is figuring out what’s happening inside their brains.” I thanked him and left. I had to get back to my task.

FROM WHAT I CAN FIND IN THE MEDICAL LIBRARIES, the history of primate research in America started with psychology experiments. An American psychologist named Robert Yerkes originally became famous for developing and administering the first large-scale intelligence test to American soldiers during World War I. Later, as a professor at Yale, Yerkes started exploring the biological basis for intelligence by comparing the brain functions of a wide variety of animals. He called this niche “psycho-biology.” In the 1920s Yerkes went further still, getting as close to the human brain as he could, by dissecting and analyzing the brains of gorillas and other high primates. His 1924 book The Mind of the Gorilla catapulted him to become the world’s leading authority on brain function. In 1928 he established the first large-scale scientific primate laboratory for Yale University, not in Connecticut, but in the warmer suburbs of Jacksonville, Florida.31 There they used lobotomies and other techniques to isolate brain function further. In 1942 the laboratory was renamed in his honor. The Yerkes lab was eventually moved to Emory University in Atlanta, nearer the Center for Disease Control. Today it is one of the seven federally funded primate research centers. Only seven, if you do not count the U.S. military’s primate laboratories.

----------------------------

----------------------------  |

For some reason, before the Delta Regional Primate Center was established, the Tulane/LSU monkey lab was unofficially referred to as the “Yerkes lab.” I say this mostly from personal experience. Growing up I repeatedly heard the New Orleans lab referred to as “ Yerkes.” As my seventh grade teacher put it, “It’s not the famous Yerkes lab, but it’s like the Yerkes lab.” During the course of researching and writing this book, I heard three separate people refer to the Delta primate lab as “Yerkes.” Further, I found a reference in a 1967 medical book to “an outbreak of hepatitis at Yerkes in New Orleans,”32 reported by Dr. Arthur Riopelle in 1963, a year before the Delta Regional Primate Center opened.

Dr. Riopelle was a psychologist specializing in brain function at the LSU Medical School in New Orleans, and he soon became the first director of the Delta Regional Primate Center. I wrote him a letter asking for clarification on the Yerkes name. He did not write back. The use of the Yerkes name for a lab in New Orleans remains somewhat of a mystery to me. But it certainly would have helped deflect any reports of misconduct in a lab if one circulated the name of another lab hundreds of miles away. When confronted with an accusation, one could say, “What are you talking about? The Yerkes lab is in Florida. You must be confused.”

Monkey research in the 1930s and 1940s was by no means confined to psychology. Monkeys were the primary means of studying many viruses, including polio. Then in the late 1940s John F. Enders, a microbiologist from Harvard, and several students figured out how to grow viruses in a test tube full of human cells. At the time, the breakthrough was hailed as the end of the monkey era.33 Today, however, there are approximately 20,000 monkeys sitting in cages in scientific laboratories across the country who might disagree with that prediction.

The second reason for maintaining a low profile was that the animal rights movement was just starting to grow. Anti-vivisectionists groups were protesting the treatment of experimental animals, and were distributing literature which showed the horrors of life and death in the animal labs. Keeping a low profile prevented such publicity from creating negative pressures on researchers and their employers.

The third reason for keeping a low profile was the secrecy demanded by covert Cold War operations. Simply said, Tulane was conducting sensitive research for the U.S. government, some of which was for the CIA. This was as much a matter of political pork as national security. Louisiana had one of the most powerful delegations in Washington, and much of that power was concentrated in the hands of legislators who controlled the military budgets. Congress works on the seniority system, and very few people had been in Washington longer than Louisiana’s most powerful members:

F. EDWARD EBERT, Chairman of Armed Services Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. Taxes start in the House, and budgets start in Committee. As Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, the entire U.S. military budget and the vast majority of the CIA budget started on Hebert’s desk. One of his jobs was to hide most of the CIA budget in the U.S. military budget. He was known as “the military’s best friend.”34

ALLEN ELLENDER had been in the U.S. Senate for over 40 years. He was the senior senator when Huey Long was the junior senator in 1930s. Ellender sat on the Armed Services Committee of the U.S. Senate and got Hebert’s budget through the Senate. Between the two, they made sure that Louisiana received its fair share of military and space contracts.35

RUSSELL LONG, the son of Huey Long, was Majority Whip of the U.S. Senate, Chairman of the Senate’s powerful Ways and Means Committee, and a member of the Senate Banking Committee.

HALE BOGGS, Majority Whip of the U.S. House of Representatives, was the 3rd most powerful man in that body, and was considered by many to be LBJ’s “man-in-the-House.”

TULANE WAS A MAJOR WATERING HOLE for the Louisiana delegation, and it got “pork” whenever they could dish it out. Hebert and Ellender were in terrific position to assure that Tulane received pork in the form of CIA research contracts. CIA projects were hidden from both Soviet and American scrutiny by placing them in other agencies’ budgets, such as the National Institutes of Health, in the various military branches, or in private foundations.36 From what I heard through Tulane’s student grapevine over the years, I must conclude that Tulane was definitely involved in both NIH- and CIA-sponsored projects, especially research with psychoactive drugs.

31 Eyestone, Willard H., “Scientific and Administrative Concepts Behind the Establishment of the U.S. Primate Centers,” Some Recent Developments in Comparative Medicine, ed. Fiennes., p. 6.

32 Fiennes, Zoonoses of Primates, p. 142; A. Riopelle and J.F. Molloy, “Infectious Hepatitis at Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology,” Laboratory Primate Newsletter, 1962, vol. 1-4, p. 12.

33 Shorter, Health Century, p. 65.

34 Word-of-mouth description of Congressman Hebert which this author personally heard in his district in the 1960s.

35 Not the least of which was the NASA facility that builds the huge fuel tank for the space shuttle. Vice-President Lyndon Johnson was head of NASA when this facility was announced, and President when it was built.

36 Marks, John, Search for the Manchurian Candidate (New York, 1980).

See footnote 37

----------------------------  |

Why would the CIA be interested in doing medical research? There were three main reasons: (1) mind control, (2) to get rid of Castro or other foreign leaders, and (3) to keep up with the Soviets.

First, mind control. The CIA’s much-publicized LSD experiments were just the beginning of their efforts to get people to talk when they wanted, to sleep when they wanted, and to kill when they wanted. Their general mind-control project was called OPERATION ARTICHOKE.38

Secondly, the CIA was trying to get rid of Fidel Castro and Communism in the Western Hemisphere. They tried to use their mind-altering resources and other medical tactics to discredit Castro. The project was called MKULTRA.39 One specific plan was to spray a hallucinogenic drug in Castro’s personal radio studio, so that he would make a fool out of himself during a national radio broadcast. Then they decided to kill him. Their new team was called ZR-RIFLE, and its job was to explore exotic ways of advancing the date of his death.40 The CIA’s medical director for these projects was brain-function expert Dr. Sidney Gottlieb.41

(The name “ Gottlieb” shows up frequently in AIDS literature. Dr. Michael S. Gottlieb is an immunologist at UCLA Medical School who “discovered AIDS” in 1981. Dr. A. Arthur Gottlieb is also an immunologist and is a professor at Tulane Medical School, as is his wife. In 1972 A. Arthur Gottlieb was chosen by the U.S. Army’s Biological Warfare Laboratory at Fort Detrick, Maryland to edit its book on infectious diseases.42 Please note that I have no information to suggest whether or not there is any relationship between Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, Dr. Michael S. Gottlieb, or Dr. A. Arthur Gottlieb, so the reader should be cautious about any such conclusions.)

One of the best sources of information on “The Secret War Against Cuba” is a book called Deadly Secrets: The CIA-Mafia War Against Castro and the Assassination of J.F.K., written by Warren Hinckle and William Turner. Turner is an ex-FBI agent who specialized in the political right. He worked with Jim Garrison on his JFK probe and was inside David Ferrie’s apartment. His writing partner Warren Hinckle was editor of Ramparts magazine. In Deadly Secrets they made numerous references to the fact that the CIA was getting the best minds in America, and particularly from the universities, involved in figuring out exotic ways to eliminate Castro and his government from Cuba.43

Hinckle and Turner explained the frustration of the Kennedy White House. After spending hundreds of millions of dollars and recruiting thousands of Cuban exiles for OPERATION Mongoose (a free Cuba paramilitary operation based on the campus of the University of Miami), the Kennedy brothers wanted to see some action. They pressured the CIA for more tangible and immediate results and encouraged the use of alternative means to remove Castro and Communism from Cuba. Consider this passage:

… The pressure for more spectacular results was on Lansdale (CIA), who was in almost daily contact with the attorney general (Bobby Kennedy). He passed the pressure on to an interagency group formulating plans for approval by the SGA (Special Group Augmented — a CIA/White House task force focused on Cuba), saying that “it is our job to put the American genius to work on this project, quickly and effectively. This demands a change from the business as usual and a hard facing of the fact that we are in a combat situation — where we have been given full command.”

Lansdale hinted that “we might uncork the touchdown play independently of the institutional program we are spurring.”44

|

Other than naming the University of Miami, Deadly Secrets does not say which universities were involved. Was Tulane one of the universities asked “to put the American genius to work”? It certainly would have fit into the economic interests and anti-Communist sentiment of the New Orleans business community. It would have fit into the tradition of close cooperation between CIA officials and certain members of the Tulane Board, most notably Sam Zemurray (who was chairman of both the United Fruit Company and the Tulane University Board of Directors in 1954, when the CIA produced a coup d’etat in Guatemala to reclaim 250,000 acres of United Fruit land which had been nationalized by Guatemala’s democratically elected government).45 And the project would have been considered “pork” by the elected political officials who were in a position to approve the budget.

And what of Lansdale’s proposal to “uncork the touchdown play independently of the institutional program”? Does this not suggest that there were some back channels open which were not officially or overtly connected to institutions? Was he referring to the CIA’s much-publicized use of the Mafia to try to kill Castro? Or might he have been referring to an underground medical laboratory run by politically sympathetic scientists who might develop a biological means of eliminating the entire Cuban leadership?

|

Thirdly, the CIA would have been interested in medical research for political reasons. In the 1950s and 1960s, Soviet scientists were ahead of U.S. scientists in certain areas of medical research, one of which was the investigation of cancer-causing monkey viruses. The Soviets were explicit, as early as 1951, about their demonstration that certain simian viruses caused a variety of cancers.46 This was six to eight years before American government researchers produced the same results. This Soviet edge was a concern for American Cold War planners, who monitored Soviet scientific journals.

From their perspective, this was just another Soviet threat. Either the Soviets might use this information to develop a sexually-transmitted biological weapon to undermine freedom in the promiscuous West, or they might develop a cure for cancer before the U.S. did and thereby cause a major American political embarrassment. Either could provide sufficient reason for the CIA not to want the U.S. to fall behind the Soviets in this important area.47

Whatever the motive, the U.S. government wanted the work done. The money was provided for researching monkey viruses through convenient channels, but the doctors were not supposed to talk about it. In the process, New Orleans became one of the leading centers of knowledge about immunology and retroviruses. The doctors at Tulane who specialized in cancer and pathology had access to this knowledge, to these monkeys, and to their viruses.

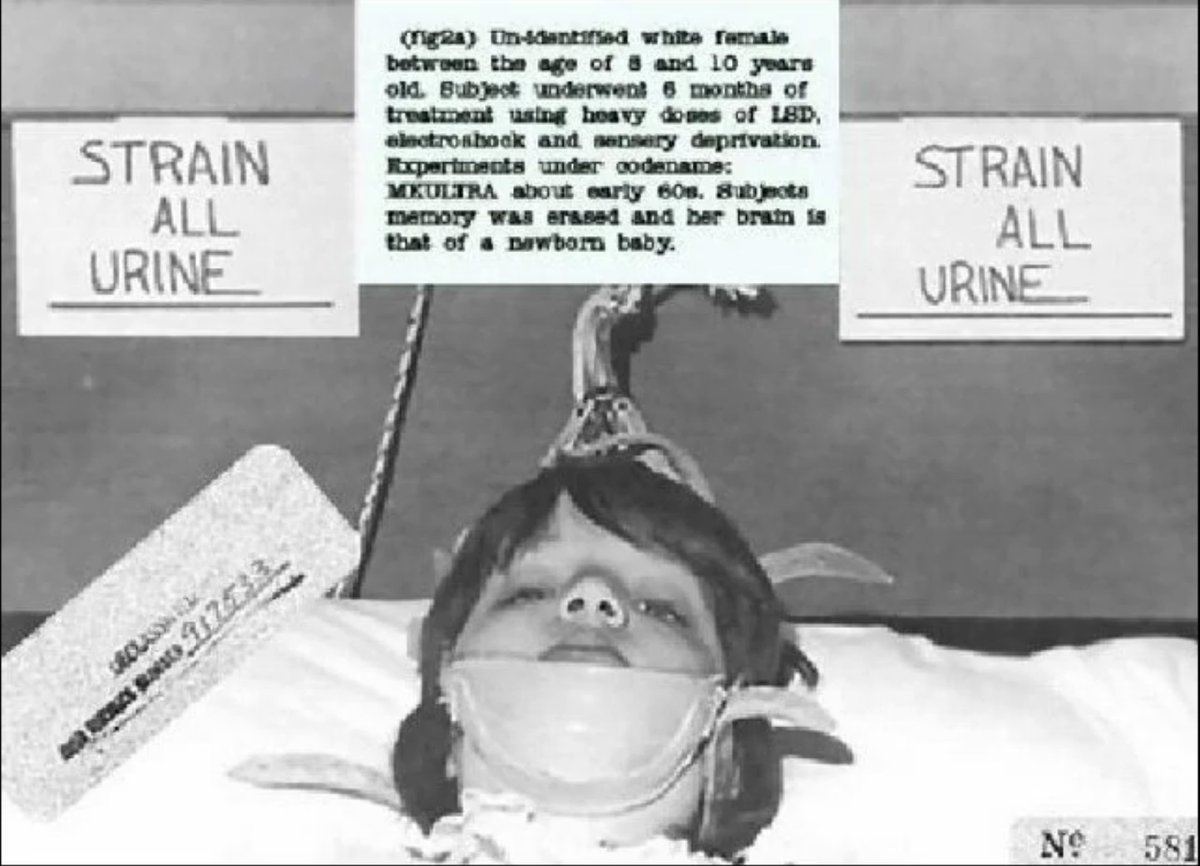

37 “Un-identified white female between the age of 8 and 10 years old. Subject underwent 6 months of treatment using heavy doses of LSD, electroshock and sensory deprivation. Experiments under codename: MKULTRA about early ’60s. Subjects memory was erased and her brain is that of a newborn baby.”

38 Russell, Dick, The Man Who Knew Too Much (New York, 1992), p.380-381.

39 Ibid., p. 380., and Project MKULTRA, the CIA’s Program of Research in Behavioral Modification, U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, August 3, 1977

40 Russell, The Man Who Knew Too Much, p. 381.

41 Ibid., p. 380.

42 Gottlieb, A. Arthur, et al., Transfer Factor (New York, 1976).

43 Hinckle, Warren and Turner, William, Deadly Secrets (New York, 1992), p. 122.

44 Ibid., p. 135. Caution: James DiEugenio told me that the source of these statements is ultimately CIA officer Howard Hunt, and that he may have fabricated them to make his anti-Castro activities to appear to have been authorized by the White House. If so, we should remember that fabricating the authorization does not equal fabricating the activity. In fact, there is little reason to fabricate the authorization unless one was trying to legitimatize an otherwise illegal activity. Or to put it bluntly, it is unlikely that someone would try to legitimatize an activity that did not exist.

45 Ibid., p. 40.

46 B.A. Lapin et al., “Use of Non-Human Primates in Medical Research, Especially in the Study of Cardiovascular Pathology and Oncology,” Institute of Experimental Pathology and Therapy, U.S.S.R., Some Recent Developments in Comparative Medicine, ed. Fiennes, p. 204.

47 Who would synthesize a disease for which there is no cure? Consider the Defense Appropriations Hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1970: “Within the next 5 to 10 years, it would probably be possible to make a new infective microorganism which would differ in certain important aspects from any known disease-causing organisms. Most important of these is that it might be refractory to the immunological and therapeutic processes upon which we depend to maintain our relative freedom from infectious disease.” While I personally do not think that this conversation led to HIV-1, it does show the thinking of a biological weapons developer. Of course, the rationale was defensive: we’d better do it before some bad guy does.

|

Jim Garrison announcing

the arrest of Clay Shaw |

CARROLLTON AVENUE is a wide, tree-lined boulevard which runs north and south, bisecting New Orleans and connecting the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain. At its mid-point, in a residential neighborhood near the corner of Canal Street, stands a huge four-story brick building resembling a fortress. It covers an entire city block. This is Jesuit High School, where the Jesuit priests have been educating the future leaders of New Orleans for over 100 years. The Jesuits are famous, even notorious, for demanding academic excellence. Therefore, the economic and power elite of this predominantly Catholic city send their male children to the Jesuits to be educated. Admission is highly competitive. Discipline is strict. Military uniforms are worn. High performance is required. And nobility is expected. The students are trained for success and for leadership roles in tomorrow’s society. Above all else, they are expected to carry the militant social conscience and uncompromising values of their Jesuit educators with them into their future roles.

I attended Jesuit High School from 1966 to 1969. During this time, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison was investigating the assassination of President Kennedy. This investigation culminated in the trial of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw in early 1969. The amount of press coverage this received in New Orleans was staggering. And much of this was a contrived media smog, aggressively negative toward Garrison. The national press had been particularly vicious, with anti-Garrison articles like “Jolly Green Giant in Wonderland.”1 They basically claimed that the New Orleans District Attorney had completely lost his marbles, was recklessly prosecuting homosexuals for spite, and suffered from paranoid delusions of grandeur.

Garrison, in turn, appeared on national television and stated in unambiguous language that a faction within the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had murdered the President of the United States. Gesturing to the camera, he waved sworn statements from witnesses who claimed that their testimony to the Warren Commission had been altered to distort important information. If that was not enough, he went further, reminding the American people that the order to hide the hard evidence (Kennedy’s x-rays and the autopsy photos) from the American people came directly from the Oval Office in the White House. Garrison said bluntly that there had been a “coup d’etat” right here in the United States and that the press had ignored it.