| I Ching (Book of Changes) |

|

The I Ching, or Book of Changes, a common source for both Confucianist and Taoist philosophy, is one of the first efforts of the human mind to place itself within the universe. The oldest of the Chinese classics, it has exerted a living influence in China for 3,000 years, and is an influential text read throughout the world — providing inspiration to the worlds of religion, psychoanalysis, business, literature, and art.

Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period (1000–750 BC), over the course of the Warring States period and early imperial period (500–200 BC) it was transformed into a cosmological text with a series of philosophical commentaries known as the "Ten Wings."

After becoming part of the Five Classics in the 2nd century BC, the I Ching was the subject of scholarly commentary and the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought.

The I Ching has been translated into Western languages dozens of times. The most influential edition is the 1923 German translation of Richard Wilhelm (1950), later translated to English by Cary Baynes (1967), has been reprinted numerous times. This tabbed page version of the I Ching is from that translation.

| Posted on 15 Oct 2017 |

The I Ching has served for thousands of years as a philosophical taxonomy of the universe, a guide to an ethical life, a manual for rulers, and an oracle of one’s personal future and the future of the state.

- It was an organizing principle or authoritative proof for literary and arts criticism, cartography, medicine, and many of the sciences, and

- It generated endless Confucian, Taoist, Buddhist, and, later, even Christian commentaries, and competing schools of thought within those traditions.

- In China and in East Asia, it has been by far the most consulted of all books, in the belief that it can explain everything.

- In the West, it has been known for over three hundred years and, since the 1950s, is surely the most popularly recognized Chinese book.

With its seeming infinitude of applications and interpretations, there has never been a book quite like it anywhere.

- It is the center of a vast whirlwind of writings and practices, but is itself a void, or perhaps a continually shifting cloud, for most of the crucial words of the I Ching have no fixed meaning.

|

The origin of the text is, as might be expected, obscure.

- In the mythological version, the culture hero Fu Xi, a dragon or a snake with a human face, studied the patterns of nature in the sky and on the earth: the markings on birds, rocks, and animals, the movement of clouds, the arrangement of the stars.

- He discovered that everything could be reduced to eight trigrams, each composed of three stacked solid or broken lines, reflecting the yin and yang, the duality that drives the universe.

- The trigrams themselves represented, respectively, heaven, a lake, fire, thunder, wind, water, a mountain, and earth (see illustration on right).

From these building blocks of the cosmos, Fu Xi devolved all aspects of civilization — kingship, marriage, writing, navigation, agriculture — all of which he taught to his human descendants.

Here mythology turns into legend.

- Around the year 1050 BCE, according to the tradition, Emperor Wen, founder of the Zhou dynasty, doubled the trigrams to hexagrams (six-lined figures), numbered and arranged all of the possible combinations — there are 64 — and gave them names.

- He wrote brief oracles for each that have since been known as the “Judgments.”

- His son, the Duke of Zhou, a poet, added gnomic interpretations for the individual lines of each hexagram, known simply as the “Lines.”

- It was said that, five hundred years later, Confucius himself wrote ethical commentaries explicating each hexagram, which are called the “Ten Wings” (“wing,” that is, in the architectural sense).

The archaeological and historical version of this narrative is far murkier.

- In the Shang dynasty (which began circa 1600 BCE) or possibly even earlier, fortune-telling diviners would apply heat to tortoise shells or the scapulae of oxen and interpret the cracks that were produced.

- Many of these “oracle bones” — hundreds of thousands of them have been unearthed — have complete hexagrams or the numbers assigned to hexagrams incised on them. Where the hexagrams came from, or how they were interpreted, is completely unknown.

Sometime in the Zhou dynasty — the current guess is around 800 BCE — the 64 hexagrams were named, and a written text was established, based on the oral traditions.The book became known as the Zhou Yi(Zhou Changes).

- The process of consultation also evolved from the tortoise shells, which required an expert to perform and interpret, to the system of coins or yarrow stalks that anyone could practice and that has been in use ever since.

- Three coins, with numbers assigned to heads or tails, were simultaneously tossed; the resulting sum indicated a solid or broken line; six coin tosses thus produced a hexagram.

- In the case of the yarrow stalks, 50 were counted out in a more laborious procedure to produce the number for each line.

A diagram of ‘I Ching’ hexagrams sent to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz from Joachim Bouvet. The Arabic numerals were added by Leibniz. |

By the third century BCE, with the rise of Confucianism, the “Ten Wings” commentaries had been added, transforming the Zhou Yi from a strictly divinatory manual to a philosophical and ethical text.

- In 136 BCE, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty declared it the most important of the five canonical Confucian books and standardized the text from among various competing versions (some with the hexagrams in a different order).

- This became the I Ching, the Book (or Classic) of Change, and its format has remained the same since: a named and numbered hexagram, an arcane “Judgment” for that hexagram, an often poetic interpretation of the image obtained by the combination of the two trigrams, and enigmatic statements on the meaning of each line of the hexagram.

- Confucius almost certainly had nothing to do with the making of the I Ching, but he did supposedly say that if he had another hundred years to live, 50 of them would be devoted to studying it.

For two millennia, the I Ching was the essential guide to the universe.

- In a philosophical cosmos where everything is connected and everything is in a state of restless change, the book was not a description of the universe but rather its most perfect microcosm.

- It represented, as one Sinologist has put it, the “underpinnings of reality.”

- Its 64 hexagrams became the irrevocable categories for countless disciplines.

- Its mysterious “Judgments” were taken as kernels of thought to be elaborated, in the “Ten Wings” and countless commentaries, into advice to rulers on how to run an orderly state and to ordinary people on how to live a proper life.

- It was a tool for meditation on the cosmos and, as a seamless piece of the way of the world, it also revealed what would be auspicious or inauspicious for the future.

In the West, the I Ching was discovered in the late 17th century by Jesuit missionaries in China, who decoded the text to reveal its Christian universal truth:

- Hexagram number one was God;

- Two was the second Adam, Jesus;

- Three was the Trinity;

- Eight was the members of Noah’s family; and so on.

Leibniz enthusiastically found the universality of his binary system in the solid and broken lines.

- Hegel — who thought Confucius was not worth translating — considered the book “superficial”: “There is not to be found in one single instance a sensuous conception of universal natural or spiritual powers.”

The first English translation was done by Canon Thomas McClatchie, an Anglican cleric in Hong Kong.

- McClatchie was a Reverend Casaubon figure who, in 1876, four years after the publication of Middlemarch, found the key to all mythologies and asserted that the I Ching had been brought to China by one of Noah’s sons and was a pornographic celebration of a “hermaphroditic monad,” elsewhere worshiped among the Chaldeans as Baal and among Hindus as Shiva.

- James Legge, also a missionary in Hong Kong and, despite a general loathing of China, the first important English-language translator of the Chinese classics, considered McClatchie “delirious.”

- After 20 interrupted years of work — the manuscript was lost in a shipwreck in the Red Sea — Legge produced the first somewhat reliable English translation of the I Ching in 1882, and the one that first applied the English word for a six-pointed star, “hexagram,” to the Chinese block of lines.

Professionally appalled by what he considered its idolatry and superstition, Legge nevertheless found himself “gradually brought under a powerful fascination,” and it led him to devise a novel theory of translation.

- Since Chinese characters were not, he claimed, “representations of words, but symbols of ideas,” therefore “the combination of them in composition is not a representation of what the writer would say, but of what he thinks.”

- The translator, then, must become “en rapport” with the author, and enter into a “seeing of mind to mind,” a “participation” in the thoughts of the author that goes beyond what the author merely said.

- Although the I Ching has no author, Legge’s version is flooded with explanations and clarifications parenthetically inserted into an otherwise literal translation of the text.

Herbert Giles, the next important English-language translator after Legge, thought the I Ching was “apparent gibberish”:

This is freely admitted by all learned Chinese, who nevertheless hold tenaciously to the belief that important lessons could be derived from its pages if only we had the wit to understand them.

Arthur Waley, in a 1933 study — he never translated the entire book — described it as a collection of “peasant interpretation” omens to which specific divinations had been added at a later date. Thus, taking a familiar Western example, he wrote that the omen

red sky in the morning, shepherds take warning” would become the divination “red sky in the morning: inauspicious; do not cross the river.

Waley proposed three categories of omens —

Inexplicable sensations and involuntary movements (‘feelings,’ twitchings, stumbling, belching and the like)

Those concerning plants, animals and birds…[and]

Those concerning natural phenomena (thunder, stars, rain etc.)

— and found examples of all of them in his decidedly unmetaphysical reading of the book.

Joseph Needham devoted many exasperated pages to the I Ching in Science and Civilization in China as a “pseudo-science” that had, for centuries, a deleterious effect on actual Chinese science, which attempted to fit exact observations of the natural and physical worlds into the “cosmic filing-system” of the vague categories of the hexagrams.

It was Richard Wilhelm’s 1924 German translation of the I Ching and especially the English translation of the German by the Jungian Cary F. Baynes in 1950 that transformed the text from Sinological arcana to international celebrity.

- Wilhelm, like Legge, was a missionary in China, but unlike Legge was an ardent believer in the Wisdom of the East, with China the wisest of all.

- The “relentless mechanization and rationalization of life in the West” needed the “Eastern adhesion to a natural profundity of soul.”

- His mission was to “join hands in mutual completion,” to uncover the “common foundations of humankind” in order to “find a core in the innermost depth of the humane, from where we can tackle…the shaping of life.”

Wilhelm’s translation relied heavily on late, Song Dynasty Neo-Confucian interpretations of the text.

- In the name of universality, specifically Chinese referents were given general terms, and the German edition had scores of footnotes noting “parallels” to Goethe, Kant, the German Romantics, and the Bible. (These were dropped for the English-language edition.)

- The text was oddly presented twice: the first time with short commentaries, the second time with more extended ones.

- The commentaries were undifferentiated amalgams of various Chinese works and Wilhelm’s own meditations. (Needham thought that the edition belonged to the “Department of Utter Confusion”: “Wilhelm seems to be the only person…who knew what it was all about.”)

The book carried an introduction by Carl Jung, whom Wilhelm considered “in touch with the findings of the East [and] in accordance with the views of the oldest Chinese wisdom.”

- (One proof was Jung’s male and female principles, the anima and the animus, which Wilhelm connected to yin and yang.)

- Some of Jung’s assertions are now embarrassing. (“It is a curious fact that such a gifted and intelligent people as the Chinese have never developed what we call science.”)

- But his emphasis on chance — or synchronicity, the Jungian, metaphysical version of chance — as the guiding principle for a sacred book was, at the time, something unexpected, even if, for true believers, the I Ching does not operate on chance at all.

The Wilhelm/Baynes Bollingen edition was a sensation in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Octavio Paz, Allen Ginsberg, Jorge Luis Borges, and Charles Olson, among many others, wrote poems inspired by its poetic language.

- Fritjof Capra in The Tao of Physics used it to explain quantum mechanics and

- Terence McKenna found that its geometrical patterns mirrored the “chemical waves” produced by hallucinogens.

- Others considered its binary system of lines a prototype for the computer.

- Philip K. Dick and Raymond Queneau based novels on it;

- Jackson Mac Low and John Cage invented elaborate procedures using it to generate poems and musical compositions.

It is not difficult to recuperate how thrilling the arrival of the I Ching was both to the avant-gardists, who were emphasizing process over product in art, and to the anti-authoritarian counterculturalists.

- It brought, not from the soulless West, but from the mysterious East, what Wilhelm called “the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years.”

- It was an ancient book without an author, a cyclical configuration with no beginning or end, a religious text with neither exotic gods nor priests to whom one must submit,

- A do-it-yourself divination that required no professional diviner.

- It was a self-help book for those who wouldn’t be caught reading self-help books, and moreover one that provided an alluring glimpse of one’s personal future.

- It was, said Bob Dylan, “the only thing that is amazingly true.”

The two latest translations of the I Ching couldn’t be more unalike; they are a complementary yin and yang of approaches.

- John Minford is a scholar best known for his work on the magnificent five-volume translation of The Story of the Stone (or The Dream of the Red Chamber), universally considered the greatest Chinese novel, in a project begun by the late David Hawkes.

- His I Ching, obviously the result of many years of study, is over 800 pages long, much of it in small type, and encyclopedic.

- Minford presents two complete translations: the “Bronze Age Oracle,” a recreation of the Zhou dynasty text before any of the later Confucian commentaries were added to it, and the “Book of Wisdom,” the text as it was elucidated in the subsequent centuries.

- Each portion of the entries for each hexagram is accompanied by an exegesis that is a digest of the historical commentaries and the interpretations by previous translators, as well as reflections by Minford himself that link the hexagram to Chinese poetry, art, ritual, history, philosophy, and mythology.

- It is a tour de force of erudition, almost a microcosm of Chinese civilization, much as the I Ching itself was traditionally seen.

David Hinton is, with Arthur Waley and Burton Watson, the rare example of a literary Sinologist — that is, a classical scholar thoroughly conversant with, and connected to, contemporary literature in English.

- A generation younger than Watson, he and Watson are surely the most important American translators of Chinese classical poetry and philosophy in the last 50 years.

- Both are immensely prolific, and both have introduced entirely new ways of translating Chinese poetry.

- Hinton’s I Ching is equally inventive. It is quite short, with only two pages allotted to each hexagram, presents a few excerpts from the original “Ten Wings” commentaries, but has nothing further from Hinton himself, other than a short introduction.

- Rather than consulted, it is meant to be read cover to cover, like a book of modern poetry — though it should be quickly said that this is very much a translation, and not an “imitation” or a postmodern elaboration.

- Or perhaps its fragments and aphorisms are meant to be dipped into at random, the way one reads E.M. Cioran or Elias Canetti.

Hinton adheres to a Taoist or Ch’an (Zen) Buddhist reading of the book, unconcerned with the Confucian ethical and political interpretations.

- His I Ching puts the reader into the Tao of nature: that is, the way of the world as it is exemplified by nature and embodied by the book.

- He takes the mysterious lines of the judgments as precursors to the later Taoist and Ch’an writings: “strategies…to tease the mind outside workaday assumptions and linguistic structures, outside the limitations of identity.”

- The opposite of Wilhelm’s Jungian self-realization, it is intended as a realization of selflessness.

- Moreover, it is based on the belief that archaic Chinese culture, living closer to the land — and a land that still had a great deal of wilderness — was less estranged from nature’s Tao.

To that end, Hinton occasionally translates according to a pictographic reading of the oldest characters, a technique first used by Ezra Pound in his idiosyncratic and wonderful version of the earliest Chinese poetry anthology, the Book of Songs, which he titled The Confucian Odes.

- For example, Hinton calls Hexagram 32 — usually translated as “Endurance” or “Duration” or “Perseverance” — “Moondrift Constancy,” because the character portrays a half-moon fixed in place with a line above and below it.

- The character for “Observation” becomes “Heron’s-Eye Gaze,” for indeed it has a heron and an eye in it, and nothing watches more closely than a waterbird.

- Hinton doesn’t do this kind of pictographic reading often, but no doubt Sinologists will be scandalized.

|

The difference between the two translations — the differences among all translations — is apparent if we look at a single hexagram: number 52, called Gen.

Minford translates the name as “Mountain” for the hexagram is composed of the two Mountain trigrams, one on top of the other. His translation of the text throughout the book is minimalist, almost telegraphese, with each line centered, rather than flush left. He has also made the exceedingly strange decision to incorporate tags in Latin, taken from the early Jesuit translations, which he claims

can help us relate to this deeply ancient and foreign text, can help create a timeless mood of contemplation, and at the same time can evoke indirect connections between the Chinese traditions of Self-Knowledge and Self-Cultivation…and…the long European tradition of Gnosis and spiritual discipline.

In the “Book of Wisdom” section, he translates the “Judgment” for Hexagram 52 as:

The back

Is still

As a Mountain;

There is no body.

He walks

In the courtyard,

Unseen.

No Harm,

Nullum malum.

This is followed by a long and interesting exegesis on the spiritual role and poetic image of mountains in the Chinese tradition.

Hinton calls the hexagram “Stillness” and translates into prose: “Stillness in your back. Expect nothing from your life. Wander the courtyard where you see no one. How could you ever go astray?”

Wilhelm has “Keeping Still, Mountain” as the name of the hexagram. His “Judgment” reads:

KEEPING STILL. Keeping his back still

So that he no longer feels his body.

He goes into the courtyard

And does not see his people.

No blame.

He explains:

True quiet means keeping still when the time has come to keep still, and going forward when the time has come to go forward. In this way rest and movement are in agreement with the demands of the time, and thus there is light in life.

The hexagram signifies the end and beginning of all movement. The back is named because in the back are located all the nerve fibers that mediate movement. If the movement of these spinal nerves is brought to a standstill, the ego, with its restlessness, disappears as it were. When a man has thus become calm, he may turn to the outside world. He no longer sees in it the struggle and tumult of individual beings, and therefore he has that true peace of mind which is needed for understanding the great laws of the universe and for acting in harmony with them. Whoever acts from these deep levels makes no mistakes.

The Columbia University Press I Ching, translated by Richard John Lynn and billed as the “definitive version” “after decades of inaccurate translations,” has “Restraint” for Gen:

Restraint takes place with the back, so one does not obtain [sic] the other person. He goes into that one’s courtyard but does not see him there. There is no blame.

Lynn’s odd explanation, based on the Han dynasty commentator Wang Bi, is that if two people have their backs turned, “even though they are close, they do not see each other.” Therefore neither restrains the other and each exercises self-restraint.

The six judgments for the six individual lines of Hexagram 52 travel through the body, including the feet, calves, waist, trunk, and jaws.

- (Wilhelm weirdly and ahistorically speculates that “possibly the words of the text embody directions for the practice of yoga.”)

- Thus, for line 2, Hinton has: “Stillness fills your calves. Raise up succession, all that will follow you, or you’ll never know contentment.”

Minford translates it as: “The calves are/Still as a Mountain./Others/Are not harnessed./The heart is heavy.” He explains: “There is a potential healing, a Stillness. But the Energy of Others…cannot be mastered and harnessed. No Retreat is possible, only a reluctant acceptance. One lacks the foresight for Retreat. Beware.”

Wilhelm’s version is: “Keeping his calves still./He cannot rescue him whom he follows./His heart is not glad.” This is glossed as:

The leg cannot move independently; it depends on the movement of the body. If a leg is suddenly stopped while the whole body is in vigorous motion, the continuing body movement will make one fall.

The same is true of a man who serves a master stronger than himself. He is swept along, and even though he himself may halt on the path of wrongdoing, he can no longer check the other in his powerful movement. When the master presses forward, the servant, no matter how good his intentions, cannot save him.

In the “Bronze Age Oracle” section — the original Zhou book without the later interpretations — Minford translates Gen as “Tending,” believing that it refers to traditional medicine and the need to tend the body.

- The “Judgment” for the entire hexagram reads: “The back/Is tended,/The body/Unprotected./He walks/In an empty courtyard./No Harm.”

- He suggests that the “empty courtyard” is a metaphor for the whole body, left untended.

- His judgement for the second line is: “The calves/Are tended./There is/No strength/In the flesh./The heart/Is sad,” which he glosses as “There is not enough flesh on the calves. Loss of weight is a concern, and it directly affects the emotions.”

Both Richard J. Smith, in a monograph on the I Ching for the Princeton Lives of Great Religious Books series, and Arthur Waley take the hexagram back to the prevalent practice in the Shang dynasty of human and animal sacrifice.

- Smith translates Gen as “cleave” (but, in an entirely different reading, says that the word might also mean “to glare at”).

- His “Judgment” is puzzling: “If one cleaves the back he will not get hold of the body; if one goes into the courtyard he will not see the person. There will be no misfortune.”

- But his reading of line two is graphic: “Cleave the lower legs, but don’t remove the bone marrow. His heart is not pleased.”

Waley thinks Gen means “gnawing,” and “evidently deals with omen-taking according to the way in which rats, mice or the like have deals with the body of the sacrificial victim when exposed as ‘bait’ to the ancestral spirit.”

- His “Judgment” is: “If they have gnawed its back, but not possessed themselves of the body,/It means that you will go to a man’s house, but not find him at home.”

- He reads line two as: “If they gnaw the calf of the leg, but don’t pull out the bone marrow, their (i.e. the ancestors’) hearts do not rejoice.”

What is certain is that Hexagram 52 is composed of two Mountain trigrams and has something to do with the back and something to do with a courtyard that is either empty or where the people in it are not seen. Otherwise, these few lines may be about:

| ■ Stillness ■ Having no expectations ■ Self-restraint ■ Peace of mind |

■ Knowing when not to follow a leader ■ The care of various aches and pains ■ Glaring at things and ■ The preparations for, and results of, human or animal sacrifices |

None of these are necessarily misinterpretations or mistranslations.

- One could say that the I Ching is a mirror of one’s own concerns or expectations.

- But it’s like one of the bronze mirrors from the Shang dynasty, now covered in a dark blue-green patina so that it doesn’t reflect at all.

- Minford recalls that in his last conversation with David Hawkes, the dying master-scholar told him: “Be sure to let your readers know that every sentence can be read in an almost infinite number of ways! That is the secret of the book. No one will ever know what it really means!”

- In the I Ching, the same word means both “war prisoner” and “sincerity.”

- There is no book that has gone through as many changes as the Book of Change.

[LINK] to original article

This article was first published in the February 25, 2016 issue of The New York Review of Books.

Eliot Weinberger

Eliot Weinberger

Eliot Weinberger’s books of literary essays include Karmic Traces, An Elemental Thing, Oranges & Peanuts for Sale, and the forthcoming The Ghosts of Birds. His political articles are collected in What I Heard About Iraq and What Happened Here: Bush Chronicles. The author of a study of Chinese poetry translation, 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, he is the current translator of the poetry of Bei Dao, the editor of The New Directions Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry, and the general editor of a series, Calligrams: Writings from and on China, co-published by Chinese University of Hong Kong Press and New York Review Books. He is also the literary editor of the Murty Classical Library of India. Among his many translations of Latin American literature are The Poems of Octavio Paz and Jorge Luis Borges’ Selected Non-Fictions. His work has been translated into over 30 languages.

The Chinese classic called I Ching (sometimes written Yi Jing, as it should be pronounced) has been interpreted a number of ways by different scholars and devotees of the text. Is it, as many who consult it claim, a book of divination? Is it more fundamentally a book of wisdom, offering suggestions of what one might do in various situations? Is it a remarkable insight into the basic archetypal possibilities of the human psyche, as Carl Jung believed, and perhaps also related to his notion of synchronicity? Is it basically a resource book that gives us some insight into the social structure of ancient China, as some scholars claim? Is it an early example of a binary number system, anticipating by millennia the switching structure of the modern digital computer? Or is it somehow all of these at once?

The great German Sinologist Richard Wilhelm translated the I Ching in 1923 based on his years of familiarity with the text and his consultation with Chinese who used it. His German translation was then rendered into English by Cary F. Baynes at Jung's request; the revised edition was printed in a new format with a preface by Richard Wilhelm's son, Hellmut, also a Sinologist. Other translations exist, of course, including one published by the Sinologist John Blofeld in 1965. The Chinese scholar Wing-tsit Chan preferred James Legge's 1882 translation. But many of us who have become intrigued with the text and cannot read the Chinese original prefer the Wilhelm-Baynes translation, even though it is, as Chan points out, "interpretative to some extent" (795). Jung, in fact, states that Legge "has done little to make the work accessible to Western minds" (Wilhelm-Baynes, xxi).

Since the Chinese language lacks inflection, the title could be translated either "Book of Change" or "Book of Changes." I prefer the former, since constant change is a basic assumption of ancient Chinese philosophy. The basis of the text is the philosophy of yang and yin, the former being associated with light, strength, affirmation, and so on, and the latter with darkness, weakness, yielding, negation, and so on. Neither is considered superior, since in some situations a dominant and forthright attitude is appropriate, while in others a more submissive attitude is needed. The proper attitude depends on one's situation and the desired outcome.

The yang principle is indicated in the I Ching by an unbroken line and the yin by a broken or divided line, hence the binary aspect of the system. The various combinations of these two lines are made by two trigrams (combinations of three lines) placed one atop the other to create a hexagram (a combination of six lines), making a total of sixty-four possible combinations. The method of reading them is from the bottom upwards. Each trigram is given a Chinese name, as is the combination of the two trigrams in a hexagram. The first hexagram according to the usual system of organization, is called in the Wade-Giles transliteration system Ch'ien, The Creative (or in Gregory Winecup's translation using the pinyin system of transliteration Qian, Strong Action), and is composed of all yang lines. The second hexagram, composed of all yin lines, is K'un, The Receptive (or Kun, Acquiescence). The subsequent hexagrams are all composed of various mixtures of yang and yin lines.

The traditional way of consulting the book is by means of yarrow stalks. It is suggested that this is because the stalks originally come from living organisms and hence are appropriate instruments for consulting what is considered to be a dynamic or living system. It is also a slower method and allows — according to some, including myself — psychokinesis (PK) to influence the stalks at a subconscious level of the psyche. The assumption seems to be that some deeper aspect of ourselves already knows what would be best for us to do in any specific situation, even if our brain-dominated consciousness does not. And that aspect of ourselves somehow influences the way the stalks are divided and counted out. If this is correct, as I believe it is, it implies that one should never consult the I Ching flippantly, disrespectfully, or casually, nor for trivial questions or problems one could easily solve for oneself. It should be used infrequently and only when one has a serious dilemma. In other words, one must attempt to get in touch with one's deeper self and not with some more superficial aspect of one's psyche.

Another method of consulting the book is by tossing ancient Chinese coins. Although they do not have the metaphorical association with life that yarrow stalks do, they at least preserve the association with ancient China. Whether PK — and one's unconscious self — can influence the result as readily is difficult to determine, although PK experiments have been conducted by parapsychologists with such materials, often with statistically significant, although not usually very exuberant, results. Some Americans use ordinary modern currency such as copper pennies, considering that they are comparable to ancient Chinese copper coins. Still more recently, a computer program has been developed that chooses one's hexagram electronically. With all such modern methods, the element of ritual involved in the use of yarrow stalks is bypassed. The few times I have witnessed these modern methods, I felt that the resulting hexagram was somehow inappropriate to the question being asked, often completely unintelligible. That is why I prefer the slower, ancient method using yarrow stalks as is described in Wilhelm-Baynes text (721-24).

Because there are obviously more than just sixty-four different situations one might find oneself in, the text offers a variety of alternatives. There are actually four possible outcomes for each of the six lines when consulting the yarrow stalks. These lines are identified either as "young yang," "young yin," "old yang," or "old yin." The young lines are fixed; that is, they remain unchanged. The old lines are moving; that is, they change into their counterparts: An old yang changes into a young yin and an old yin into a young yang. It is unusual to arrive at a hexagram containing only fixed lines, which suggests a situation that one cannot change and simply has to accept. Equally uncommon would be to arrive at a hexagram with six moving lines, indicating an extremely fluid situation. More common is a hexagram with at least one or two moving lines. In that case, one gets two hexagrams: the starting one and the one it changes into. That suggests possibilities for solving (or resolving) one's present situation creatively instead of reactively, which often happens when one deals with life's problems based on past habit patterns.

Another important aspect of the I Ching is that each hexagram has both a judgment and an image associated with it (collectively called the kua-tz'u), both of which are expressed in metaphors. The text describing each of the possible moving lines (known as the yao-tz'u) is also expressed metaphorically. The vagueness involved in both is important, since it allows one's subconscious — perhaps even one's higher self — to interpret the hexagram in a way that is appropriate to oneself. Two people with two different problems arriving at the same hexagram might appropriately interpret it in different ways according to the nature of their question. In other words, the I Ching is a remarkable book with an almost infinite range of possible answers to life's dilemmas.

In addition to the kua-tz'u and yao-tz'u, there are several commentaries, probably appended to the basic text over several centuries. The most interesting from a theosophical point of view is the wen yen, which stresses the philosophical and ethical implications of the hexagrams. As Wing-tsit Chan observes, it is upon that commentary and some appended remarks (hsi-tz'u), as well as comments on some of the trigrams, "that much of Chinese philosophical speculation has been based" (262).

Just when the I Ching was compiled is difficult to determine. Tradition ascribes the eight trigrams to the legendary hero Fu-hsi (traditionally dated prior to the twenty-third century BCE) and their development into the hexagrams to King Wen (reigned 1171-1122 BCE), although modern scholars dispute this. Hellmut Wilhelm points out only that it is generally agreed that there are several layers of the text, the present form having been reached "in the century before Confucius" (Wilhelm-Baynes xiv). It is known that Confucius (551-479 BCE) included it among the classics (ching) he required his students to study, and it is believed that he wrote a commentary on it (called "The Ten Wings"), although this also has been disputed by some scholars (Chan 262). One assumes that Confucius considered it a book of wisdom rather than of divination, perhaps relating to earlier times before China began to degenerate into interstate warfare (which started during his lifetime but became endemic during 403-222 BCE, called the Warring States period). Confucius looked to the past as a model for restoring political order. In any event, the I Ching assumed great importance in later centuries in China, especially when the examination system required aspirants for government positions to write essays on the Confucian classics.

Theosophical references to China are scarce and to the I Ching even scarcer. H. P. Blavatsky makes several references to Confucius in The Secret Doctrine, but most of them make little sense and none relates in any obvious way to the I Ching. It is a shame, because this Chinese classic, however it is construed, is most interesting. And when it is used as a book of divination — or, if one prefers, of wisdom — it can be extremely illuminating. I have known several theosophists, including both my wife and myself, who consult it when confronted with a difficult situation that we cannot solve with either reason or intuition. It has always proven useful. In one case, which occurred at a theosophical planning seminar I attended, the hexagram, Splitting Apart (po or bo), was a literal description of our situation. It also gave us sensible advice for resolving our impasse, which we did. However, in many cases, the really difficult thing is not interpreting its recommendations but putting them into practice!

by Richard Brooks [LINK] to original

References

Chan, Wing-tsit. A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

Wilhelm, Richard, trans. The I Ching or Book of Changes. Rendered into English by Cary F. Baynes. Bolllinger Series XIX. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1971

Richard Brooks is a retired professor and chair of the Department of Philosophy at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan. As a Theosophist of more than fifty years, he served on the national board for many years. His specialties are logic, Indic and Chinese philosophy, and parapsychology.

Richard Brooks is a retired professor and chair of the Department of Philosophy at Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan. As a Theosophist of more than fifty years, he served on the national board for many years. His specialties are logic, Indic and Chinese philosophy, and parapsychology.

|

I left the US with only a handfull of books, the most important of which is the I Ching. It's been with me since 1970, and read more often than any other.

I'm happy to be able to give back in this small way, for all I've received from this Great Work.

Pictured at right is an image of the copyright page with the publication date from my copy of the I Ching — a constant companion for 54 years.

|

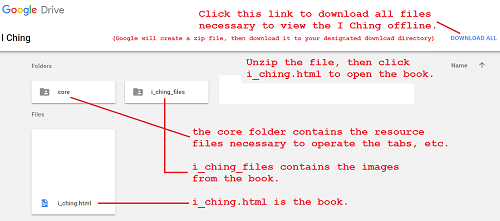

@ Google Drive |

|

Download this tabbed-page version of the I Ching

from my Google Drive @: https://goo.gl/62KwjK

Once there, click on "DOWNLOAD ALL" as pictured.

Click on either folder to inspect the files.

All the files, located in their respective folders, are necessary to view the book "offline".

The entire package is approximately 2.5MB.

The Book of Changes – I Ching in Chinese – is unquestionably one of the most important books in the world's literature.

- Its origin goes back to mythical antiquity, and it has occupied the attention of the most eminent scholars of China down to the present day.

- Nearly all that is greatest and most significant in the three thousand years of Chinese cultural history has either taken its inspiration from this book, or has exerted an influence on the interpretation of its text.

- Therefore it may safely be said that the seasoned wisdom of thousands of years has gone into the making of the I Ching.

- Small wonder then that both of the two branches of Chinese philosophy, Confucianism and Taoism, have their common roots here.

- The book sheds new light on many a secret hidden in the often puzzling modes of thought of that mysterious sage, Lao-tse, and of his pupils, as well as on many ideas that appear in the Confucian tradition as axioms, accepted without further examination.

Indeed, not only the philosophy of China but its science and statecraft as well have never ceased to draw from the spring of wisdom in the I Ching, and it is not surprising that this alone, among all the Confucian classics, escaped the great burning of the books under Ch'in Shih Huang Ti.[1]

- Even the common-places of everyday life in China are saturated with its influence.

- In going through the streets of a Chinese city, one will find, here and there at a street corner, a fortune teller sitting behind a neatly covered table, brush and tablet at hand, ready to draw from the ancient book of wisdom pertinent counsel and information on life's minor perplexities.

- Not only that, but the very signboards adorning the houses –perpendicular wooden panels done in gold on black lacquer – are covered with inscriptions whose flowery language again and again recalls thoughts and quotations from the I Ching.

- Even the policy makers of so modern a state as Japan, distinguished for their astuteness, do not scorn to refer to it for counsel in difficult situations.

In the course of time, owing to the great repute for wisdom attaching to the Book of Changes, a large body of occult doctrines extraneous to it – some of them possibly not even Chinese in origin – have come to be connected with its teachings.

- The Ch'in and Han dynasties[2] saw the beginning of a formalistic natural philosophy that sought to embrace the entire world of thought in a system of number symbols.

- Combining a rigorously consistent, dualistic yin-yang doctrine with the doctrine of the "five stages of change" taken from the Book of History,[3] it forced Chinese philosophical thinking more and more into a rigid formalization.

- Thus increasingly hairsplitting cabalistic speculations came to envelop the Book of Changes in a cloud of mystery, and by forcing everything of the past and of the future into this system of numbers, created for the I Ching the reputation of being a book of unfathomable profundity.

- These speculations are also to blame for the fact that the seeds of a free Chinese natural science, which undoubtedly existed at the time of Mo Ti[4] and his pupils, were killed, and replaced by a sterile tradition of writing and reading books that was wholly removed from experience.

- This is the reason why China has for so long presented to Western eyes a picture of hopeless stagnation.

Yet we must not overlook the fact that apart from this mechanistic number mysticism, a living stream of deep human wisdom was constantly flowing through the channel of this book into everyday life, giving to China's great civilization that ripeness of wisdom, distilled through the ages, which we wistfully admire in the remnants of this last truly autochthonous culture.

What is the Book of Changes actually? In order to arrive at an understanding of the book and its teachings, we must first of all boldly strip away the dense overgrowth of interpretations that have read into it all sorts of extraneous ideas.

- This is equally necessary whether we are dealing with the superstitions and mysteries of old Chinese sorcerers or the no less superstitious theories of modern European scholars who try to interpret all historical cultures in terms of their experience of primitive savages.[5]

- We must hold here to the fundamental principle that the Book of Changes is to be explained in the light of its own content and of the era to which it belongs.

- With this the darkness lightens perceptibly and we realize that this book, though a very profound work, does not offer greater difficulties to our understanding than any other book that has come down through a long history from antiquity to our time.

| Footnotes

[1] 213 B.C. [2] Beginning in the last half of the third century B.C. and ending about A.D. 220. [3] Sho Ching, the oldest of the Chinese classics. Modern scholarship has placed most of the records contained in the Shu Ching near the first millennium B.C., though formerly a much greater age was ascribed to the earliest of them. [4] Fifth and fourth centuries B.C. [5] We might mention here, because of its oddity, the grotesque and amateurish attempt on the part of Rev. Canon McClatchie, M.A., to apply the key of "comparative mythology" to the I Ching. His book was published in 1876 under the title, A Translation of the Confucian Yi King or the Clossic of Changes, with Notes and Appendix. |

The Book of Oracles

At the outset, the Book of Changes was a collection of linear signs to be used as oracles.[6]

- In antiquity, oracles were everywhere in use; the oldest among them confined themselves to the answers yes and no. This type of oracular pronouncement is likewise the basis of the Book of Changes.

- "Yes" was indicated by a simple unbroken line (___), and

- "No" by a broken line (_ _).

- However, the need for greater differentiation seems to have been felt at an early date, and the single lines were combined in pairs:

To each of these combinations a third line was then added. In this way the eight trigrams[7] came into being.

- These eight trigrams were conceived as images of all that happens in heaven and on earth.

- At the same time, they were held to be in a state of continual transition, one changing into another, just as transition from one phenomenon to another is continually taking place in the physical world.

- Here we have the fundamental concept of the Book of Changes. The eight trigrams are symbols standing for changing transitional states; they are images that are constantly undergoing change.

- Attention centers not on things in their state of being – as is chiefly the case in the Occident – but upon their movements in change.

- The eight trigrams therefore are not representations of things as such but of their tendencies in movement.

[6] From the discussion here presented, it will become self-evident that the Book of Changes was not a lexicon, as has been assumed in many quarters.

[7] Zeichen, meaning sign, is used by Wilhelm to denote the linear figures in the I Ching, those of three lines as well as those of six lines. The Chinese word for both types of signs is kua. To avoid ambiguity, the precedent established by Legge (The Sacred Books of the East, XVI: The Yi King) has been adopted througout: the term "trigram" is used for the sign consisting of three lines, and "hexagram" for the sign consisting of six lines.

Click to view larger image

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

These eight images came to have manifold meanings.

- They represented certain processes in nature corresponding with their inherent character.

- Further, they represented a family consisting of father, mother, three sons, and three daughters, not in the mythological sense in which the Greek gods peopled Olympus, but in what might be called an abstract sense, that is, they represented not objective entities but functions.

A brief survey of these eight symbols that form the basis of the Book of Changes yields the following classification:

- The sons represent the principle of movement in its various stages

• beginning of movement

• danger in movement

• rest and completion of movement - The daughters represent devotion in its various stages

• gentle penetration

• clarity and adaptability

• joyous tranquility

In order to achieve a still greater multiplicity, these eight images were combined with one another at a very early date, whereby a total of sixty-four signs was obtained.

- Each of these sixty-four signs consists of six lines, either positive or negative.

- Each line is thought of as capable of change, and whenever a line changes, there is a change also of the situation represented by the given hexagram.

K'un, THE RECEPTIVE |

Fu, RETURN |

Let us take for example the hexagram K'un, THE RECEPTIVE, earth:

- It represents the nature of the earth, strong in devotion;

- Among the seasons it stands for late autumn, when all the forces of life are at rest.

If the lowest line changes, we have the hexagram Fu, RETURN:

- The latter represents thunder, the movement that stirs anew within the earth at the time of the solstice; it symbolizes the return of light.

As this example shows, all of the lines of a hexagram do not necessarily change; it depends entirely on the character of a given line.

- A line whose nature is positive, with an increasing dynamism, turns into its opposite, a negative line,

- Whereas a positive line of lesser strength remains unchanged.

- The same principle holds for the negative lines.

More definite information about those lines which are to be considered so strongly charged with positive or negative energy that they move, is given in book II[*] in the Great Commentary (pt. I, chap. IX), and in the special section on the use of the oracle at the end of book III[*].Suffice it to say here that:

- Positive lines that move are designated by the number 9, and

- Negative lines that move by the number 6.

- While non-moving lines, which serve only as structural matter in the hexagram, without intrinsic meaning of their own, are represented by the number 7 (positive) or the number 8 (negative).

| 8 at the top | |

| 8 in the fifth place | |

| 8 in the fourth place | |

| 8 in the third place | |

| 8 in the second place | |

| 6 at the beginning |

Thus, when the text reads, "Nine at the beginning means..." this is the equivalent of saying:

"When the positive line in the first place is represented by the number 9, it has the following meaning..."

If, on the other hand, the line is represented by the number 7, it is disregarded in interpreting the oracle.

The same principle holds for lines represented by the numbers 6 and 8[8]respectively.

We may obtain the hexagram named in the example above – K'un, THE RECEPTIVE – in the form displayed at right:

K'un, THE RECEPTIVE |

Fu, RETURN |

Hence the five upper lines are not taken into account; only the 6 at the beginning has an independent meaning, and by its transformation into its opposite, the situation K'un, THE RECEPTIVE, becomes the situation Fu, RETURN:

In this way we have a series of situations symbolically expressed by lines,

- And through the movement of these lines the situations can change one into another.

On the other hand, such change does not necessarily occur,

- For when a hexagram is made up of lines represented by the numbers 7 and 8 only, there is no movement within it, and only its aspect as a whole is taken into consideration.

[*] Richard Wilhelm's translation of the I Ching includes three books: Book I – The Text, Book II – The Material, and Book III – The Commentaries. This tabbed-pages version includes (currently) only The Text.

[8] For this reason, the numbers 7 and 8 ,never appear in the portion of the text dealing with the meanings of the individual lines.

In addition to the law of change and to the images of the states of change as given in the sixty-four hexagrams, another factor to be considered is the course of action.

- Each situation demands the action proper to it. In every situation, there is a right and a wrong course of action.

- Obviously, the right course brings good fortune and the wrong course brings misfortune.

Which, then, is the right course in any given case? This question was the decisive factor.

- As a result, the I Ching was lifted above the level of an ordinary book of soothsaying.

- If a fortune teller on reading the cards tells her client that she will receive a letter with money from America in a week, there is nothing for the woman to do but wait until the letter comes – or does not come.

- In this case what is foretold is fate, quite independent of what the individual may do or not do. For this reason fortune telling lacks moral significance.

- When it happened for the first time in China that someone, on being told the auguries for the future, did not let the matter rest there hut asked, "What am I to do?" the book of divination had to become a book of wisdom.

It was reserved for King Wên, who lived about 1150 B.C., and his son, the Duke of Chou, to bring about this change.

- They endowed the hitherto mute hexagrams and lines, from which the future had to be divined as an individual matter in each case, with definite counsels for correct conduct.

- Thus the individual came to share in shaping fate. For his actions intervened as determining factors in world events, the more decisively so, the earlier he was able with the aid of the Book of Changes to recognize situations in their germinal phases. The germinal phase is the crux.

- As long as things are in their beginnings they can be controlled, but once they have grown to their full consequences they acquire a power so overwhelming that man stands impotent before them.

- Thus the Book of Changes became a book of divination of a very special kind. The hexagrams and lines in their movements and changes mysteriously reproduced the movements and changes of the macrocosm.

- By the use of yarrow stalks,[9] one could attain a point of vantage from which it was possible to survey the condition of things. Given this perspective, the words of the oracle would indicate what should be done to meet the need of the time.

The only thing about all this that seems strange to our modern sense is the method of learning the nature of a situation through the manipulation of yarrow stalks.

- This procedure was regarded as mysterious, however, simply in the sense that the manipulation of the yarrow stalks makes it possible for the unconscious in man to become active.

- All individuals are not equally fitted to consult the oracle. It requires a clear and tranquil mind, receptive to the cosmic influences hidden in the humble divining stalks.

- As products of the vegetable kingdom, these were considered to be related to the sources of life. The stalks were derived from sacred plants.

[9] The stalks come from the plant known to us as common yarrow, or milfoil (Achillea millefelium).

Of far greater significance than the use of the Book of Changes as an oracle is its other use, namely, as a book of wisdom.

- Laotse[10] knew this book, and some of his profoundest aphorisms were inspired by it. Indeed, his whole thought is permeated with its teachings.

- Confucius[11] too knew the Book of Changes and devoted himself to reflection upon it. He probably wrote down some of his interpretative comments and imparted others to his pupils in oral teaching.

- The Book of Changes as edited and annotated by Confucius is the version that has come down to our time.

If we inquire as to the philosophy that pervades the book, we can confine ourselves to a few basically important concepts.

- The underlying idea of the whole is the idea of change.

- It is related in the Analects[12] that Confucius, standing by a river, said: "Everything flows on and on like this river, without pause, day and night."

- This expresses the idea of change. He who has perceived the meaning of change fixes his attention no longer on transitory individual things but on the immutable, eternal law at work in all change.

- This law is the tao[13] of Lao-tse, the course of things, the principle of the one in the many.

- That it may become manifest, a decision, a postulate, is necessary.

- This fundamental postulate is the "great primal beginning" of all that exists, t'ai chi – in its original meaning, the "ridgepole."

- Later Chinese philosophers devoted much thought to this idea of a primal beginning.

- A still earlier beginning, wu chi, was represented by the symbol of a circle. Under this conception, t'ai chi was represented by the circle divided into the light and the dark, yang and yin,

.[14]

.[14]

This symbol has also played a significant part in India and Europe.

- However, speculations of a gnostic-dualistic character are foreign to the original thought of the I Ching; what it posits is simply the ridgepole, the line.

- With this line, which in itself represents oneness, duality comes into the world, for the line at the same time posits an above and a below, a right and left, front and back-in a word, the world of the opposites.

These opposites became known under the names yin and yang and created a great stir, especially in the transition period between the Ch'in and Han dynasties, in the centuries just before our era, when there was an entire school of yin-yang doctrine.

- At that time, the Book of Changes was much in use as a book of magic, and people read into the text all sorts of things not originally there.

- This doctrine of yin and yang, of the female and the male as primal principles, has naturally also attracted much attention among foreign students of Chinese thought.

- Following the usual bent, some of these have predicated in it a primitive phallic symbolism, with all the accompanying connotations.

To the disappointment of such discoverers it must be said that there is nothing to indicate this in the original meaning of the words yin and yang.

- In its primary meaning yin is "the cloudy," "the overcast," and yang means actually "banners waving in the sun,"[15] that is, something "shone upon," or bright.

- By transference the two concepts were applied to the light and dark sides of a mountain or of a river.

- In the case of a mountain the southern is the bright side and the northern the dark side, while in the case of a river seen from above, it is the northern side that is bright (yang), because it reflects the light, and the southern side that is in shadow (yin).

- Thence the two expressions were carried over into the Book of Changes and applied to the two alternating primal states of being.

- It should be pointed out, however, that the terms yin and yang do not occur in this derived sense either in the actual text of the book or in the oldest commentaries.

- Their first occurrence is in the Great Commentary, which already shows Taoistic influence in some parts.

- In the Commentary on the Decision the terms used for the opposites are "the firm" and "the yielding," not yang and yin.

| Footnotes

[10] Second half of fifth century B.C. [11] 551-479 B.C. [12] Lun Yü, IX, 16. This book comprises conversations of Confucius and his disciples. [13] Here, as throughout the book, Wilhelm uses the German word Sinn ("meaning") in capitals (SINN) for the Chinese word tao (see p.297 and n. 1). The reasons that led Wilhelm to choose SINN to represent tao (see p. XIV of the introduction to his translation of Lao-tse: Tao Te King: Das Buch des Alten von Sinn und Leben, 3rd edn., Düsseldorf and Cologne, 1952) have no relation to the English word "meaning." Therefore in the English rendering, "tao" has been used wherever SINN occurs. [14] Known as t'ai chi t'u, "the supreme ultimate." See R. Wilhelm, A Short History of Chinese Civilization, tr. by J. Joshua (London, 1929), p.249. [15] Cf. the noteworthy discussions of Liang Ch'i-ch'ao in the Chinese journal The Endeavor, July 15 and 22, 1923, also the English essay by B. Schindler, "The Development of the Chinese Conceptions of Supreme Beings," Asia Major, Hirth Anniversary Volume (London: Probsthain, n.d.), pp. 298-366. |

However, no matter what names are applied to these forces, it is certain that the world of being arises out of their change and interplay.

- Thus change is conceived of partly as the continuous transformation of the one force into the other and partly as a cycle of complexes of phenomena, in themselves connected, such as day and night, summer and winter.

- Change is not meaningless – if it were, there could be no knowledge of it – but subject to the universal law, tao.

The second theme fundamental to the Book of Changes is its theory of ideas.

- The eight trigrams are images not so much of objects as of states of change.

- This view is associated with the concept expressed in the teachings of Lao-tse, as also in those of Confucius, that every event in the visible world is the effect of an "image," that is, of an idea in the unseen world.

- Accordingly, everything that happens on earth is only a reproduction, as it were, of an event in a world beyond our sense perception, as regards its occurrence in time, it is later than the suprasensible event.

- The holy men and sages, who are in contact with those higher spheres, have access to these ideas through direct intuition and are therefore able to intervene decisively in events in the world.

- Thus man is linked with heaven, the suprasensible world of ideas, and with earth, the material world of visible things, to form with these a trinity of the primal powers.

This theory of ideas is applied in a twofold sense.

- The Book of Changes shows the images of events and also the unfolding of conditions in statu nascendi.

- Thus, in discerning with its help the seeds of things to come, we learn to foresee the future as well as to understand the past.

- In this way the images on which the hexagrams are based serve as patterns for timely action in the situations indicated.

- Not only is adaptation to the course of nature thus made possible, but in the Great Commentary (pt. II, chap. II), an interesting attempt is made to trace back the origin of all the practices and inventions of civilization to such ideas and archetypal images.

- Whether or not the hypothesis can be made to apply in all specific instances, the basic concept contains a truth.[16]

The third element fundamental to the Book of Changes are the judgments.

- The judgments clothe the images in words, as it were; they indicate whether a given action will bring good fortune or misfortune, remorse or humiliation.

- The judgments make it possible for a man to make a decision to desist from a course of action indicated by the situation of the moment but harmful in the long run. In this way he makes himself independent of the tyranny of events.

- In its judgments, and in the interpretations attached to it from the time of Confucius on the Book of Changes opens to the reader the richest treasure of Chinese wisdom; at the same time it affords him a comprehensive view of the varieties of human experience, enabling him thereby to shape his life of his own sovereign will into an organic whole and so to direct it that it comes into accord with the ultimate tao lying at the root of all that exists.

[16] Cf. the extremely important discussions of Hu Shih in The Development of the Logical Method in Ancient China (2nd edn., New York: Paragon, 1963), and the even more detailed discussion in the first volume of his history of philosophy [Chung-kuo chê-hsüeh-shih ta-kang; not available in translation].

In Chinese literature four holy men are cited as the authors of the Book of Changes, namely, Fu Hsi, King Wên, the Duke of Chou, and Confucius.

- Fu Hsi is a legendary figure representing the era of hunting and fishing and of the invention of cooking.

- The fact that he is designated as the inventor of the linear signs of the Book of Changes means that they have been held to be of such antiquity that they antedate historical memory.

- Moreover, the eight trigrams have names that do not occur in any other connection in the Chinese language, and because of this they have even been thought to be of foreign origin.

- At all events, they are not archaic characters, as some have been led to believe by the half accidental, half intentional resemblances to them appearing here and there among ancient characters.[17]

The eight trigrams are found occurring in various combinations at a very early date. Two collections belonging to antiquity are mentioned:

- First, the Book of Changes of the Hsia dynasty,[18] is called Lien Shan, which is said to have begun with the hexagram Kên, KEEPING STILL, mountain;

- Second, the Book of Changes dating from the Shang dynasty,[19] is entitled Kuei Ts'ang, which began with the hexagram K'un, THE RECEPTIVE.

- The latter circumstance is mentioned in passing by Confucius himself as a historical fact.

- It is difficult to say whether the names of the sixty-four hexagrams were then in existence, and if so, whether they were the same as those in the present Book of Changes.

According to general tradition, which we have no reason to challenge, the present collection of sixty-four hexagrams originated with King Wên,[20] progenitor of the Chou dynasty.

- He is said to have added brief judgments to the hexagrams during his imprisonment at the hands of the tyrant Chou Hsin.

- The text pertaining to the individual lines originated with his son, the Duke of Chou.

- This form of the book, entitled the Changes of Chou (Chou I), was in use as an oracle throughout the Chou period, as can be proven from a number of the ancient historical records.

This was the status of the book at the time Confucius came upon it.

- In his old age he gave it intensive study, and it is highly probable that the Commentary on the Decision (T'uan Chuan) is his work.

- The Commentary on the Images also goes back to him, though less directly.

- A third treatise, a very valuable and detailed commentary on the individual lines, compiled by his pupils or by their successors, in the form of questions and answers, survives only in fragments.[21]

Among the followers of Confucius, it would appear, it was principally Pu Shang (Tzú Hsia) who spread the knowledge of the Book of Changes.

- With the development of philosophical speculation, as reflected in the Great Learning (Ta Hsüeh) and the Doctrine of the Mean (Chung Yung),[22] this type of philosophy exercised an ever increasing influence upon the interpretation of the Book of Changes.

- A literature grew up around the book, fragments of which – some dating from an early and some from a later time – are to be found in the so-called Ten Wings.

- They differ greatly with respect to content and intrinsic value.

The Book of Changes escaped the fate of the other classics at the time of the famous burning of the books under the tyrant Ch'in Shih Huang Ti.

- Hence, if there is anything in the legend that the burning alone is responsible for the mutilation of the texts of the old books, the I Ching at least should be intact; but this is not the case.

- In reality it is the vicissitudes of the centuries, the collapse of ancient cultures, and the change in the system of writing that are to be blamed for the damage suffered by all ancient works.

After the Book of Changes had become firmly established as a book of divination and magic in the time of Ch'in Shih Huang Ti, the entire school of magicians (fang shih) of the Ch'in and Han dynasties made it their prey.

- And the yin-yang doctrine, which was probably introduced through the work of Tsou Yen,[23] and later promoted by Tung Chung Shu, Liu Hsin, and Liu Hsiang,[24] ran riot in connection with the interpretation of the I Ching.

The task of clearing away all this rubbish was reserved for a great and wise scholar, Wang Pi,[25] who wrote about the meaning of the Book of Changes as a book of wisdom, not as a book of divination.

- He soon found emulation, and the teachings of the yin-yang school of magic were displaced, in relation to the book, by a philosophy of statecraft that was gradually developing.

- In the Sung[26] period, the I Ching was used as a basis for the t'ai chi t'u doctrine – which was probably not of Chinese origin – until the appearance of the elder Ch'êng Tzú's[27] very good commentary.

- It had become customary to separate the old commentaries contained in the Ten Wings and to place them with the individual hexagrams to which they refer.

- Thus the book became by degrees entirely a textbook relating to statecraft and the philosophy of life.

- Then Chu Hsi[28] attempted to rehabilitate it as a book of oracles; in addition to a short and precise commentary on the I Ching, he published an introduction to his investigations concerning the art of divination.

The critical-historical school of the last dynasty also took the Book of Changes in hand.

- However, because of their opposition to the Sung scholars and their preference for the Han commentators, who were nearer in point of time to the compilation of the Book of Changes, they were less successful here than in their treatment of the other classics.

- For the Han commentators were in the last analysis sorcerers, or were influenced by theories of magic.

- A very good edition was arranged in the K'ang Hsi[29] period, under the title Chou I Chê Chung; it presents the text and the wings separately and includes the best commentaries of all periods.

- This is the edition on which the present translation is based.

| Footnotes

[17] Question has centered especially upon the trigram K'an [18] According to tradition, 2205-1766 B.C. [19] According to tradition, 1766-1150 B.C. [20] King Wên was the head of a western state that suffered oppression from the house of Shang (Yin). He was given the title of king posthumously by his son Wu, who overthrew Chou Hsin, took possession of the Shang realm, and became the first ruler of the Chou dynasty, which in traditional chronology is dated 1150-249 B.C. [21] Some are in the section known as the Wên Yen (Commentary on the Words of the Text), some in the Ta Chuan (Great Commentary). [Cf. p. xix.] [22] The Great Learning presents the Confucian principles concerning the education of the "superior man," based on the view that innate within man are the qualities that when developed guide him to a personal and a social ethic. The Doctrine of the Mean shows that the "way of the superior man" leads to harmony between heaven, man, and earth. Both of these works belong to the school of thought led by Tzú-ssú, grandson of Confucius. They originally formed part of the Li Chi, the Book of Rites. Under the titles Ta Hsio and Kung Yung they can be found as bks. 39 and 28 in Legge's translation of the Book of Rites (The Sacred Books of the East, XXVII: The Li Ki, Oxford, 1885). [23] Fourth century B.C. [24] All three are Han scholars. [25] A.D. 226-249. [26] A.D. 960-1279. [27] Ch'êng Hao, A.D. 1032-1085. [28] A.D. 1130-1200. [29] A.D. 1662-1722. |

An exposition of the principles that have been followed in the translation of the Book of Changes should be of essential help to the reader.

The translation of the text has been given as brief and concise a form as possible, in order to preserve the archaic impression that prevails in the Chinese.

- This has made it all the more necessary to present not only the text but also digests of the most important Chinese commentaries.

- These digests have been made as succinct as possible and afford a survey of the outstanding contributions made by Chinese scholarship toward elucidation of the book.

- Comparisons with Occidental writings,[30] which frequently suggested themselves, as well as views of my own, have been introduced as sparingly as possible a invariably been expressly identified as such.

- The reader may therefore regard the text and the commentary as genuine renditions of Chinese thought.

- Special attention is called to this fact because many of the fundamental truths presented are so closely parallel to Christian tenets that the impression is often really striking.

In order to make it as easy as possible for the layman to understand the I Ching, the texts of the sixty-four hexagrams, together with pertinent interpretations, are presented in book 1.

- The reader will do well to begin by reading this part with his attention fixed on its main ideas and without allowing himself to be distracted by the imagery.

- For example, he should follow through the idea of the Creative in its step-by-step development — as delineated in masterly fashion in the first hexagram — taking the dragons for granted for the moment. In this way he will gain an idea of what Chinese wisdom has to say about the conduct of life.

The second and third books explain why all these things are as they are.

- Here the material essential to an understanding of the structure of the hexagrams has been brought together, but only so much of it as is absolutely necessary, and as far as possible only the oldest material, as preserved in the Ten Wings, is presented.

- So far as has been feasible, these commentaries have been broken down and apportioned to the relevant parts of the text, in such a way as to afford a better understanding of them — their essential content having been made available earlier in the commentary summaries in book 1.

- Therefore, for one who would plumb the depths of wisdom in the Book of Changes, the second and third books are indispensable. On the other hand, the Western reader's power of comprehension ought not to be burdened at the outset with too much that is unfamiliar.

- Consequently it has not been possible to avoid a certain amount of repetition, but such reiteration will be of help in obtaining a thorough understanding of the book.

- It is my firm conviction that anyone who really assimilates the essence of the Book of Changes will be enriched thereby in experience and in true understanding of life.

R.W.

[30] A number of footnote quotations from German poetry, chiefly passages from Goethe, have been omitted in the English rendering because their poetic suggestiveness disappears in translation.

|

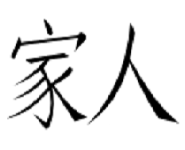

| 37. Chia Jên / The Family [The Clan] |

| Presented without comment |

THE FAMILY shows the laws operative within the household that, transferred to outside life, keep the state and the world in order.

The family is society in embryo; it is the native soil on which performance of moral duty is made easy through natural affection, so that within a small circle a basis of moral practice is created, and this is later widened to include human relationships in general.

|

For there is nothing more easily avoided and more

difficult to carry through than "breaking a child's will." |

Nine at the beginning means:

Firm seclusion within the family.

Remorse disappears.

The family must form a well-defined unit within which each member knows his place.

- From the beginning each child must be accustomed to firmly established rules of order, before ever its will is directed to other things.

- If we begin too late to enforce order, when the will of the child has already been overindulged, the whims and passions, grown stronger with the years, offer resistance and give cause for remorse.

- For there is nothing more easily avoided and more difficult to carry through than "breaking a child's will."