| Gurdjieff and Hypnosis | A Hermeneutic Study | Source |

|

This book was selected to accompany the two posts above: “Mass Formation and Totalitarian Thinking in This Time of Global Crisis” [LINK] and “Trance-Formation” by Max Igan [LINK]. I could have used only Chapter Four of this book, “The ‘Organ Kundabuffer’ Theory of Human Disharmonization” to accomplish this “other perspective” on Mass/Trance-Formation, but as Gurdjieff noted,

“If you go on a spree then go the whole hog including the postage.”

As time passes and events unfold, I become more and more convinced that what Gurdjieff ‘acquired’ and passed on to posterity was a Limited Hangout by advanced beings/advanced consciousness.

And while I do not necessarily agree with all of what Gurdfieff says about the ‘Organ Kundabuffer’ nor with all of what Tamdgidi writes about in Chapter Four, I do believe there is valid and valuable information for those wanting to learn more about the ‘Human Condition’.

FWIW, a review of Gurdjieff and Hypnosis by the idolize-Gurdjieff community is presented in the toggle at right.

|

Click for review

Review from The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation [LINK] In his resolute and densely argued Gurdjieff and Hypnosis: A Hermeneutic Study, Mohammad H. (Behrooz) Tamdgidi admits to being drawn to the Work ideas, as he sees the need for an understanding that goes beyond mere "knowing." Recognizing that "alone [one] can do little"1, he attended a number of spiritual retreats (though, strangely, given his interest, none are Gurdjieffian). At one such retreat he suddenly "awoke" to its hypnotic influences. He uses this to justify his not joining a group2 because he must "maintain distance3 to avoid being trapped" in what he calls the "Yezidi circle" of hypnosis. Therefore he believes he writes from an independent scholastic stance, the unstated assumption that he is unbiased, and, of course, that he is not one of the hypnotized. As an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, holding a Ph.D. in Sociology with a graduate certificate in Middle Eastern studies,Tamdgidi certainly has the scholastic credentials to apply a theory of interpretation known as hermeneutics4 to Gurdjieff's texts (oddly, he waits until the last page of his book to mention Gurdjieff's first writing, The Struggle of the Magicians, a ballet scenario which gives a many dimensional representation of the depth behind what Gurdjieff brought). Hermeneutics is an analytical approach traditionally used with the study of scripture, the intent is "both to conduct an in-depth textual analysis and to interpret the text using its own symbolic and meaning structures." His sole purpose, Tamdgidi says, is to "engage with Gurdjieff's life5 and teachings in his own terms … considering not only what is included but also what is excluded … as being equally significant."6 Further, he writes: "It is not a question of merely what is included and what not, but a question of where and when one or another data, thought, and idea is inserted inside a text. It is not that the data is necessarily omitted, but that it is omitted from this place and yet is then inserted in that place."7 As to what Gurdjieff includes, that can certainly be known, but what is excluded and why is open to judgment. As to the way he wrote, he purposely used what is commonly known as a "salting technique" (not mentioned by Tamdgidi) by which he "buried the dog." Tamdgidi's main thesis is that Gurdjieff's writings themselves were conscious, intentional, and systematic efforts in literary hypnotism. That the same might be said of the Old and New Testaments and the Koran doesn't seem to occur to Tamdgidi. But beyond that he misses Gurdjieff's saying that the ideas in All and Everything have three meanings and seven aspects. That the ideas are salted throughout the three series of books demands that the reader be active, not passive, toward the material and so, their intellectual intuition engaged, suddenly see the connections,thus being moved from what Gurdjieff calls the "reason of knowledge" to the "reason of understanding." Given his careful exposition of the approach of hermeneutics, it is odd to see Tamdgidi regularly deviating from its strictures. For example, he references supportive material external to Gurdjieff's writings, such as Ouspensky's In Search of the Miraculous, to address concepts such as the enneagram and self-remembering,8 but even more intellectually entrapping, introduces new words and concepts, such as a discussion of food "circuits." At one point he even proposes that The Herald of Coming Good and "The Material Question" are in fact books of the Third Series, hardly concepts presented in the material itself, and on the face of it rather laughable. No less so the idea that Gurdjieff was hypnotized by his father. This he attributes to Gurdjieff's adult understanding but it is pure Tamdgidi projection. Almost half of the book is the author's attempt to represent through condensation, intricate diagrams and interpretation of (a subset of) the concepts presented in All and Everything, which he relegates to the level of "philosophy"9 (something Gurdjieff generally held in low esteem, though he did believe Kant's Critique of Pure Reason had missed only scale). Tamdgidi's depiction of an "observing self"10 as opposed to observing is not an accurate summarization of Gurdjieff's words. Note also should be taken of the author's extensive use of quotes around individual words. Ostensibly, Tamdgidi is simply noting words that receive emphasis in Gurdjieff's writing. But what is the cumulative effect (a kind of "hypnotism"11 of which he accuses Gurdjieff) of repeatedly seeing "ancient," "knowledge," and "being" in quotes? Perhaps a questioning of the veracity of these terms? That what Gurdjieff is presenting is not authentic? How does he know this never having been in the Work? A scholastic, or as Gurdjieff calls them, "learned being of new formation," the author places himself at an equal or higher level to the material being presented. He documents and analyzes myriad (seeming) inconsistencies in the writings, never understanding that it is for the reader to break through the hypnotic literacy;12 a homeopathic fighting fire with fire whose subtlety completely eludes the author. He muses on the experiments on theosophical "guinea pigs," reported in Herald, postulating that these experiments were hypnotic in nature. Tamdgidi presents himself as a scholar whose sole purpose is to divine the "actual" intention13 behind Gurdjieff's writings. But as the reader works his way through its factual spins, supposition, argument, declaration and counter declaration—for example, Gurdjieff is a black magician but later not a black magician really—the question arises: just where is the author coming from? An Internet search reveals he is the founder of The Omar Khayyam Center for Integrative Research in Utopia, Mysticism, and Science (Utopystics14). Tamdgidi writes: Since the world's utopian,15 mystical, and scientific movements have been the primary sources of inspiration, knowledge, and/or practice in this field, [the center] aims to critically reexamine the limits and contributions of these world-historical traditions—seeking to clearly understand why they have failed to bring about the good society. … The center aims to develop new conceptual … structures of knowledge whereby the individual can radically understand and determine how world-history and her/his selves constitute one another. [Emphasis added.] As Tamdgidi16 names his center, for Omar Khayyam, one wonders if Khayyam is anything more than the philosopher, mathematician and poet he is commonly known as. According to Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr, a revered Sufi himself, in his Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, he names him a Sufi. Then one remembers that early in his book Tamdgidi says that his intellectual analysis of Gurdjieff has been augmented by meditation practices from other traditions. But he does not identify them or say how they helped his analysis. The intuition suddenly springs to mind—could Tamdgidi, an Iranian, be a closeted Sufi or one much under their influence?17 If so, the hidden agenda behind his project becomes clear: the intention is not to give an independent appraisal of Gurdjieff and his writings, but rather to present him as a flawed individual and his writings as a failed attempt to waken humanity and so skew Gurdjieff's Fourth Way teaching; this a long held Sufi aim and obsession. If so, it aligns with another Sufi, Idries Shah, who some 40 years ago tried something of the same with Teachers of Gurdjieff. Touted as nonfiction, it caused a great stir. Unmasked as fiction, it died on the shelf. While Tamdgidi's analysis isn't fiction, it falls on its own petard. It is hardly independent; rather it is an intellectual attempt at hypnotic propaganda. —Marc Cleven 1. Alone [one] can do little. Mohammad H. Tamdgidi Gurdjieff and Hypnosis: A Hermeneutic 2. Joining a group, Tamdgidi, p. xx. 3. Maintain distance, Tamdgidi, p. xxii. 4. Hermeneutics. Tamdgidi, p. xvi. 5. Engage with Gurdjieff's life. Tamdgidi, p. xxiii. 6. Considering not only what is included. Tamdgidi, p. 21. 7. It is not a question. Tamdgidi 8. Self-remembering. The term "remembering oneself" is mentioned only three times across both the First and Second Series, though mentioned several times in the Third Series. 9. Relegates to "philosophy." Approach of Paul Beekman Taylor who first met Gurdjieff in December 1948 and traveled with him and others later the following year. According to Taylor, when Gurdjieff first saw "Polo," as he was known, he threw his food at him and later told him he would "tell many stories." Taylor never joined the Work. Since retiring as a professor of medieval literature, he has written several books on Gurdjieff drawing on his many contacts in the teaching (he was raised by Jean Toomer and his half sister Eve is Gurdjieff's daughter) and, as predicted, he told many stories. For reviews of his books, see back issues. Accordingly, Taylor gives Tamdgidi a bountiful back cover blurb, as does Basarab Nicolescu, who writes about the Work but whose only experience was with a group, albeit a faux group, in Berkeley in the late 1970s. Of J. Walter Driscoll, who writes a laudatory introduction to the book, and is cited many times in footnotes, his Work connection is not known other than to say he was initially the student of E. J. Gold. 10. Observing self. Tamdgidi, p. 64. See also p. 116. 11. Conscious, intentional, and systematic efforts in literary hypnotism. p. xxff. 12. Literary hypnotism. Tamdgidi's search for inner composition would have been better served had he read Mary Douglas's Thinking in Circles (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), which examines the ring composition in scripture and classical literature. 13. Actual intentions. Tamdgidi, p. 208. 14. Utopystics. Tamdgidi, p. xviii. 15. Since the world's utopian. http://www.okcir.com. 16. Mohammad H. (Behrooz) Tamdgidi. http://www.okcir.com. 17. Omar Khayyam. Idries Shah, The Sufis (New York: Anchor Books Edition, 1971), pp. 185–93 |

A passage from the ‘Mass Formation’ video that prompted me to make the effort to put Gurdjieff and Hypnosis online along with the two mentioned videos about Mass/Trance-Formation is copied below:

(00:55:35): But that in itself, even if we would succeed in waking up the masses now, they would fall prey to a different story in a few years. And they would be hypnotized again, IF, IF we do not succeed in solving the real problem of this crisis. Namely the question: Why did we as a society get in this state in which a large part of the population feels anxious, depressed, experiences a lack of sense, feels socially isolated? That is the real problem. And if we do not succeed in finding out where this problem comes from then the masses will always be susceptible to leaders who try to lure them into a mass formation. So I think the real question in this crisis is: What is there in our view of man and of the world in the way in which we look at life that makes us experience lack of sense-making? In my opinion we must conclude that it is something in our materialistic mechanistic view of man in the world that leads up to a radical destruction of the real social structures and social bonds and of the feeling that life makes sense.

(00:57:05): If you believe that human beings are a machine, a biological machine, then by definition this implies that life is senseless. What would the sense be of a life that is reduced, for a human being, if it is reduced to a little mechanistic part of the larger machine of the universe? if you look at the universe and that the human being like that, then I’m afraid that you always end up by concluding that life is meaningless, and that you don’t really have to invest energy in social relations, that you don’t have to follow real ethical principles. In this way you destroy your psychological energy and your connectedness and you end up in free-floating anxiety and so on [bold added].

Unfortunately the theory, of unconscious procreation evolving to conscious procreation as being the sense and significance of man's purpose in life, is not considered (at least beyond this website).

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Conclusion |

Foreword Prologue Introduction Philosophy: Ontology of the Harmonious Universe Philosophy: Psychology of a “Tetartocosmos” Philosophy: Epistemology of “Three-Brained Beings” The “Organ Kundabuffer” Theory of Human Disharmonization The Practice of “Harmonious Development of Man” Life Is Real Only Then, When “I Am” Not Hypnotized Meetings With the Remarkable Hypnotist Beelzebub’s Hypnotic Tales to His Grandson Gurdjieff’s Roundabout Yezidi Circle Appendix Bibliography |

v vii x 1 9 14 20 27 34 44 59 67 70 86 |

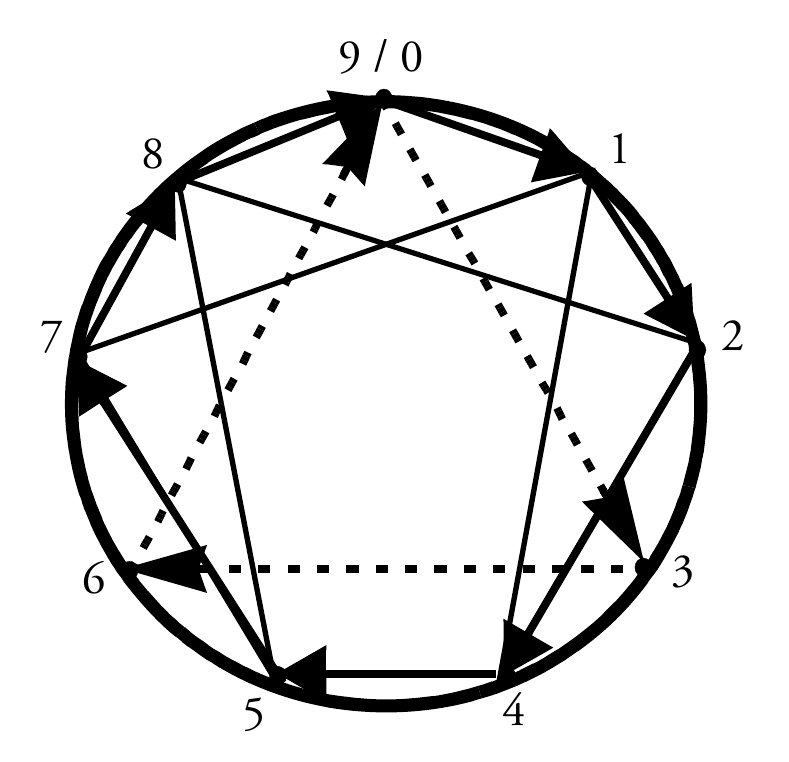

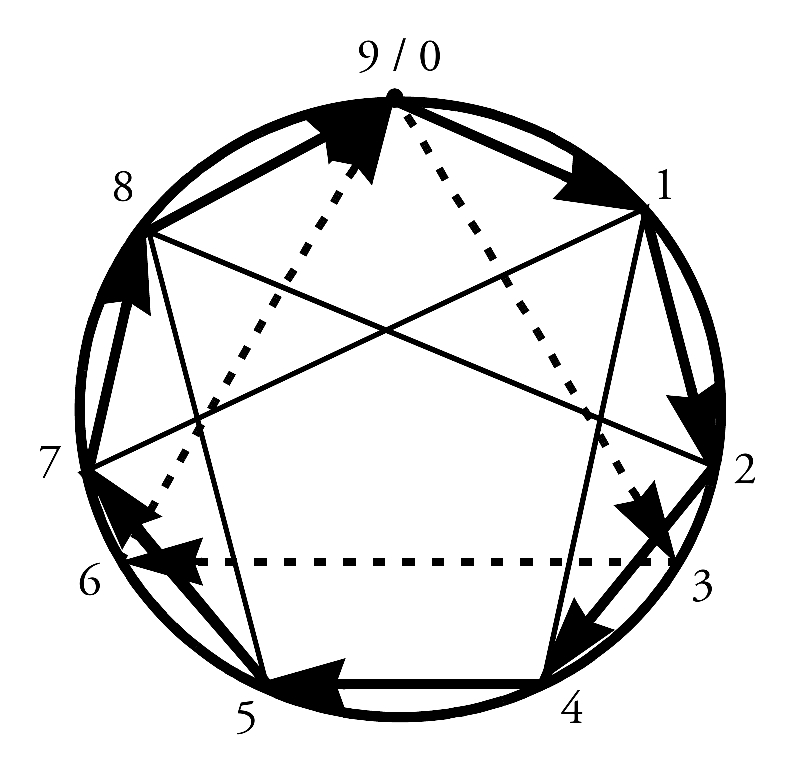

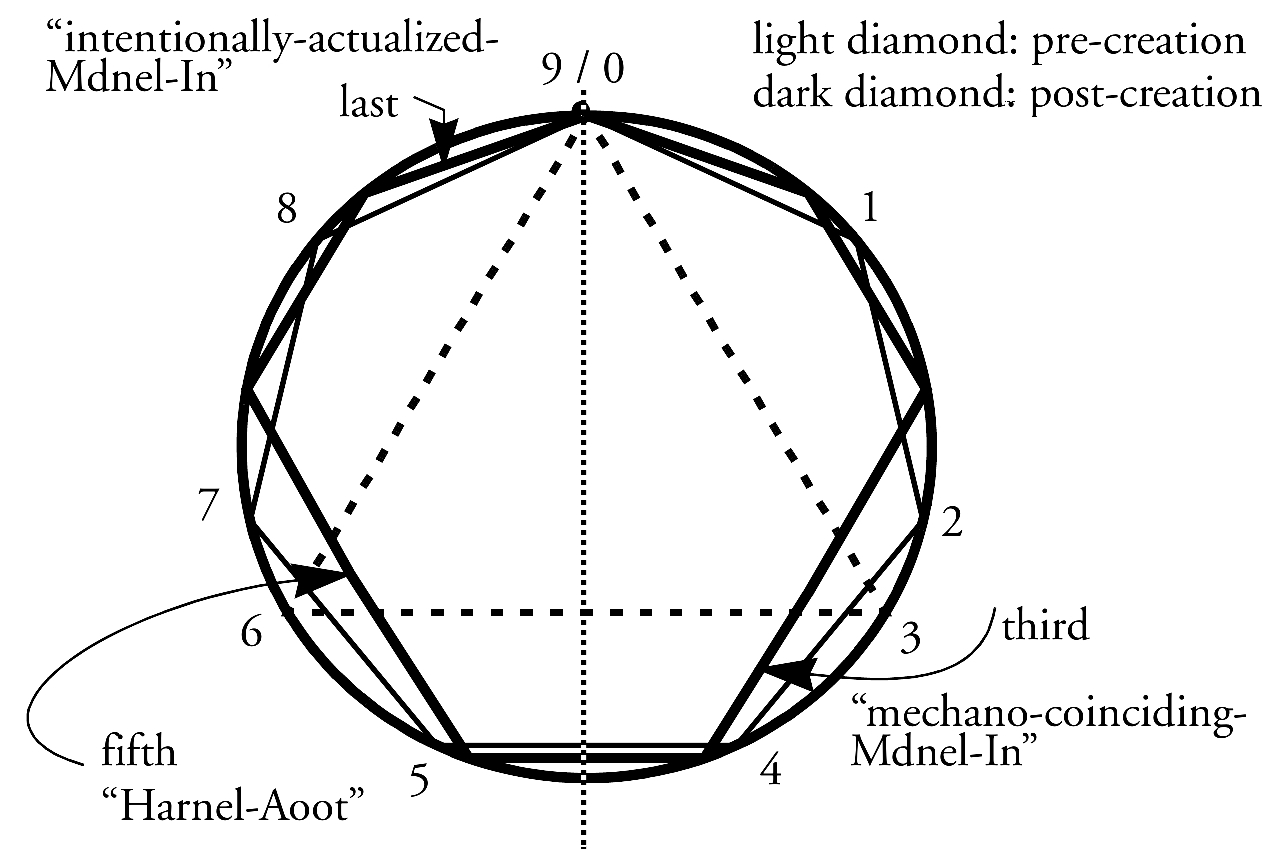

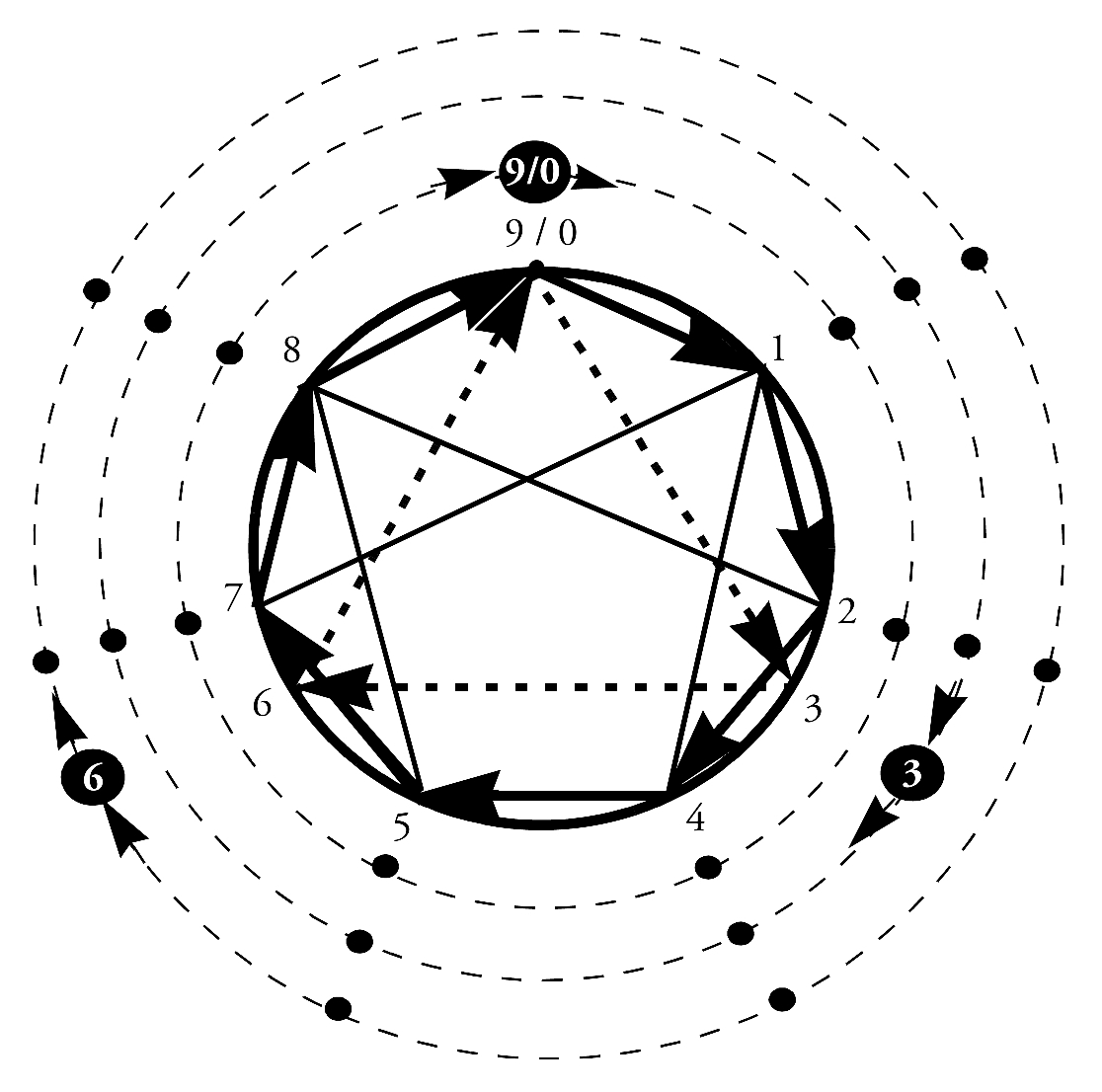

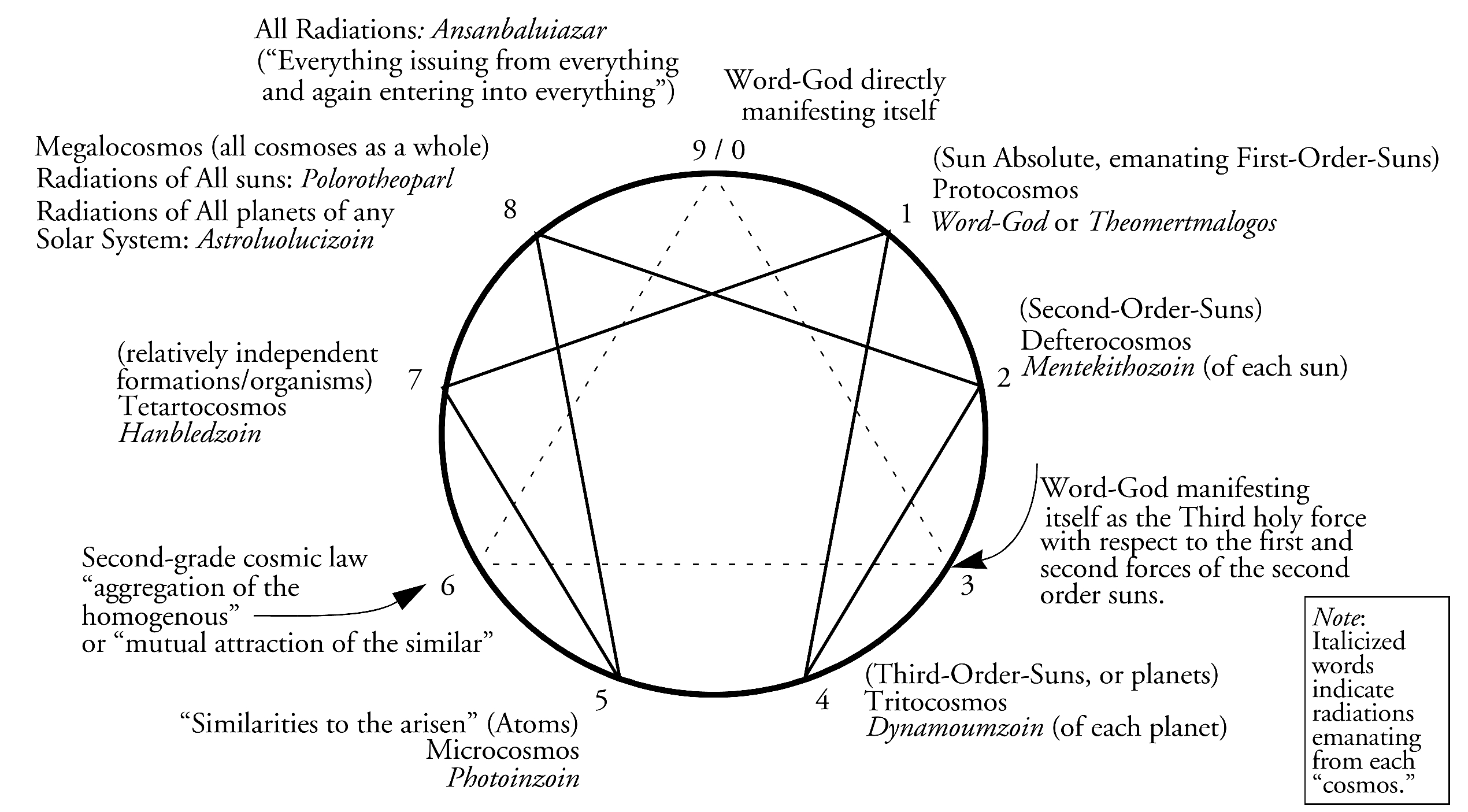

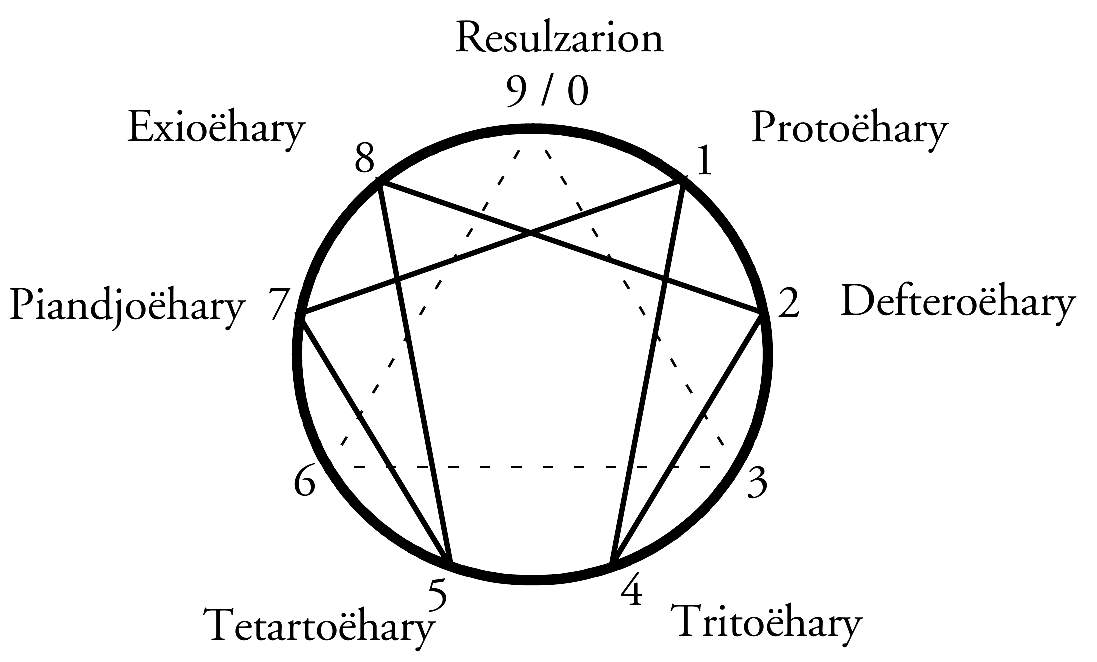

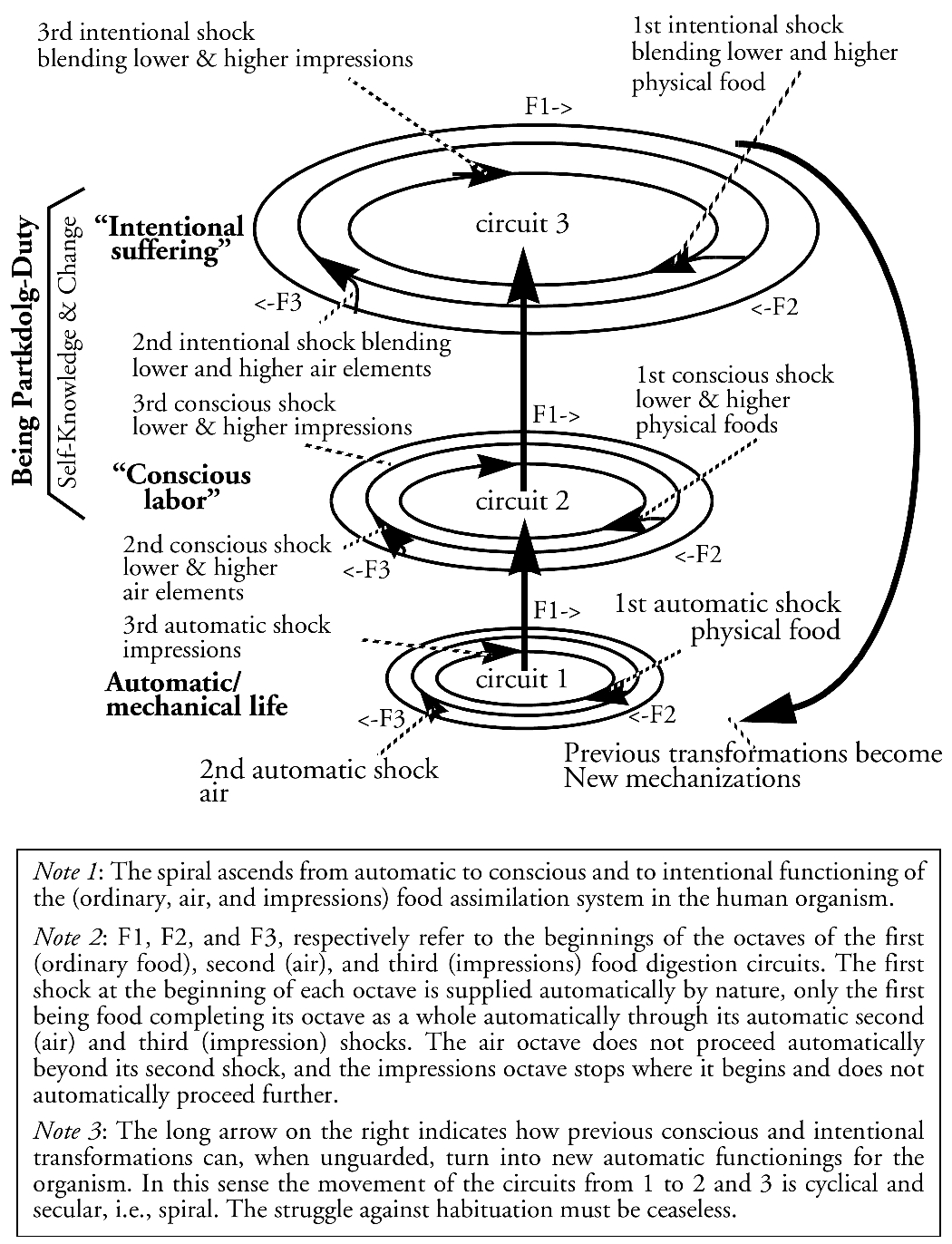

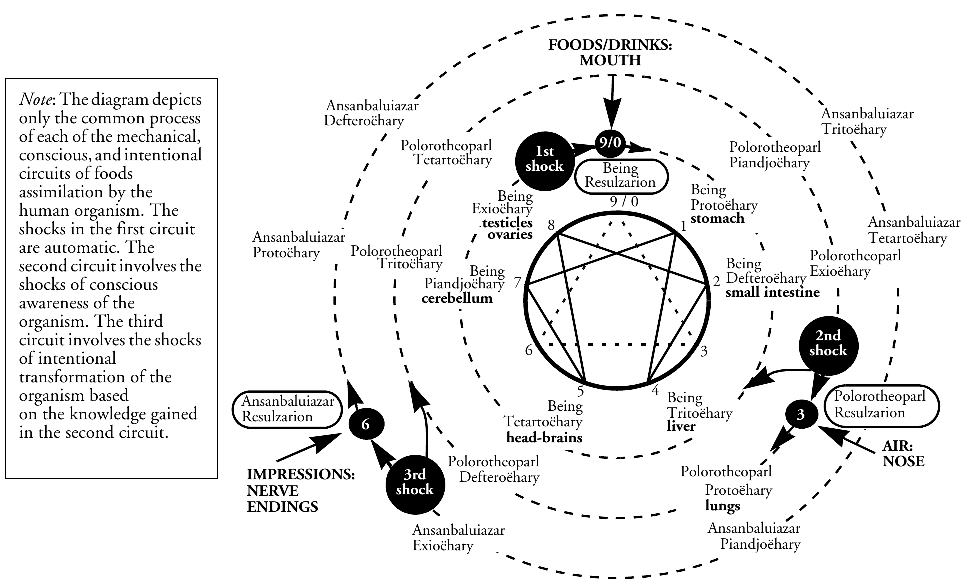

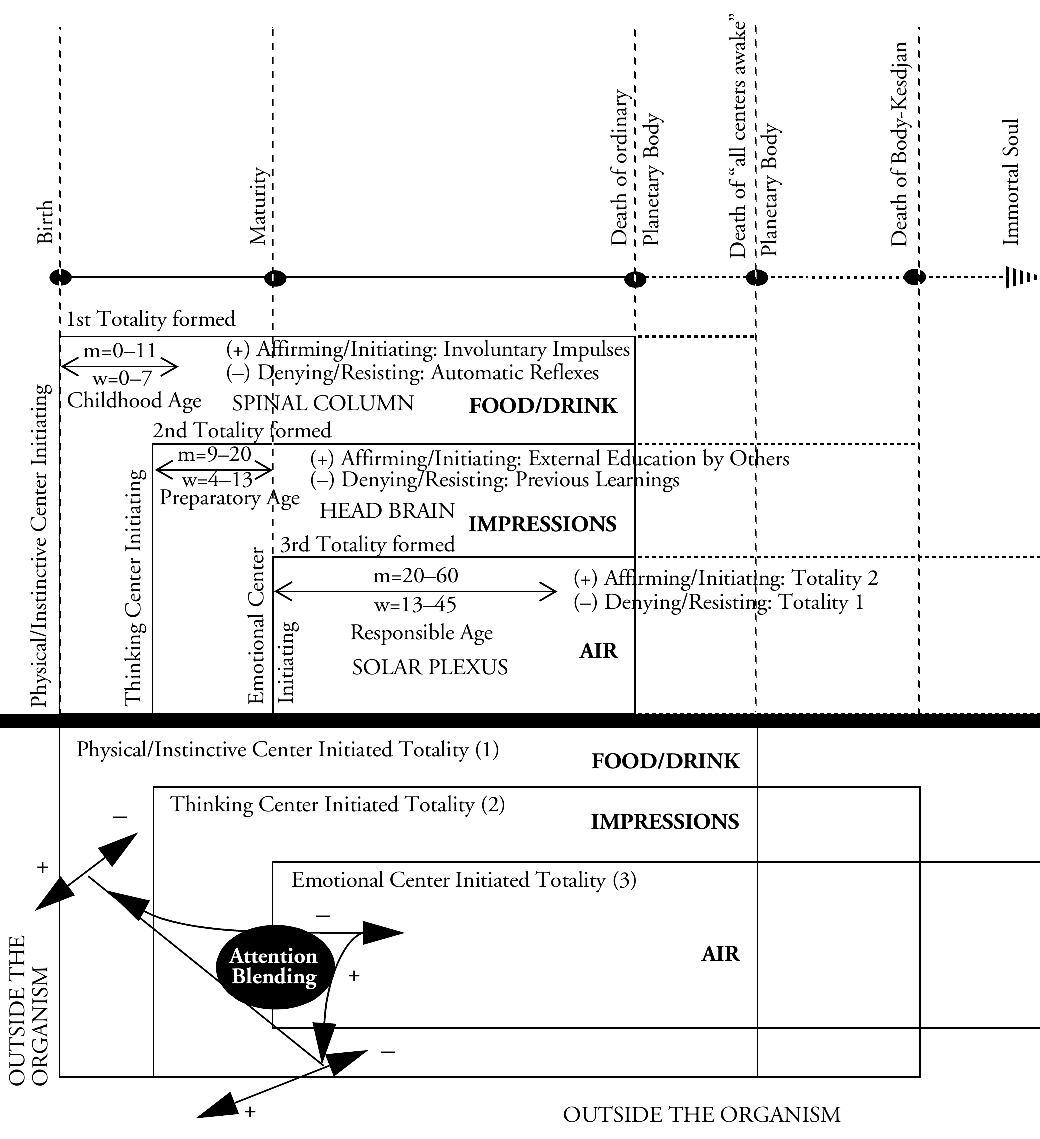

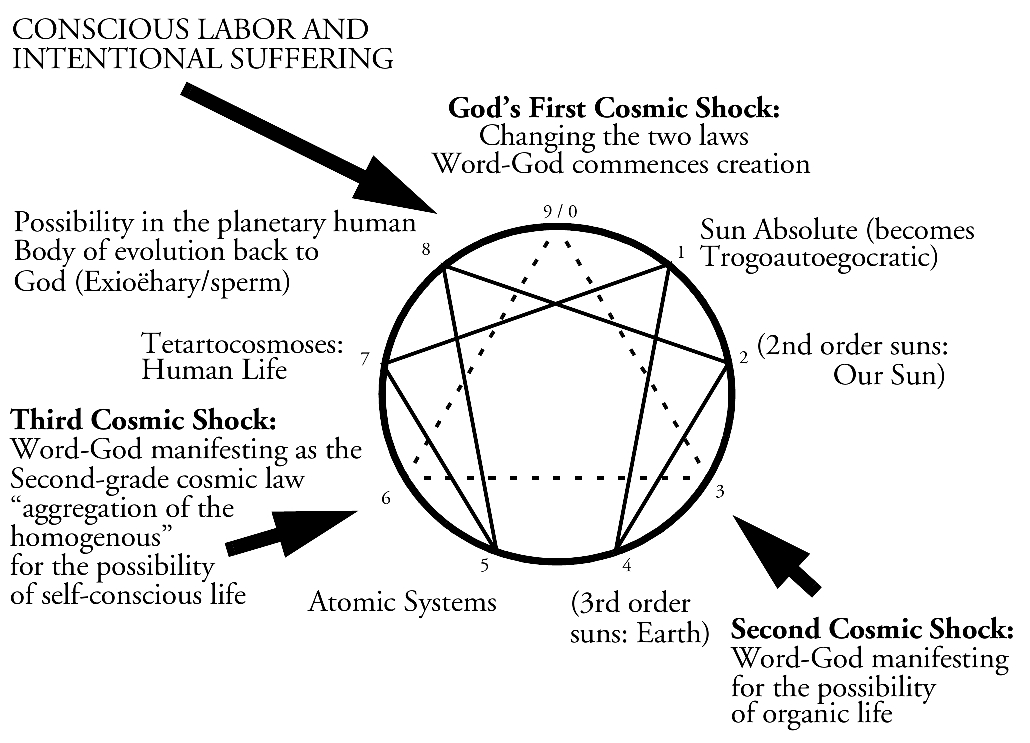

| Figure 1.1 Figure 1.2 Figure 1.3 Figure 1.4 Figure 1.5 Figure 1.6 Figure 2.1 Figure 2.2 Figure 3.1 Figure 3.2 Figure 4.1 Figure 6.1 Figure 7.1 Figure 7.2 Figure C.1 |

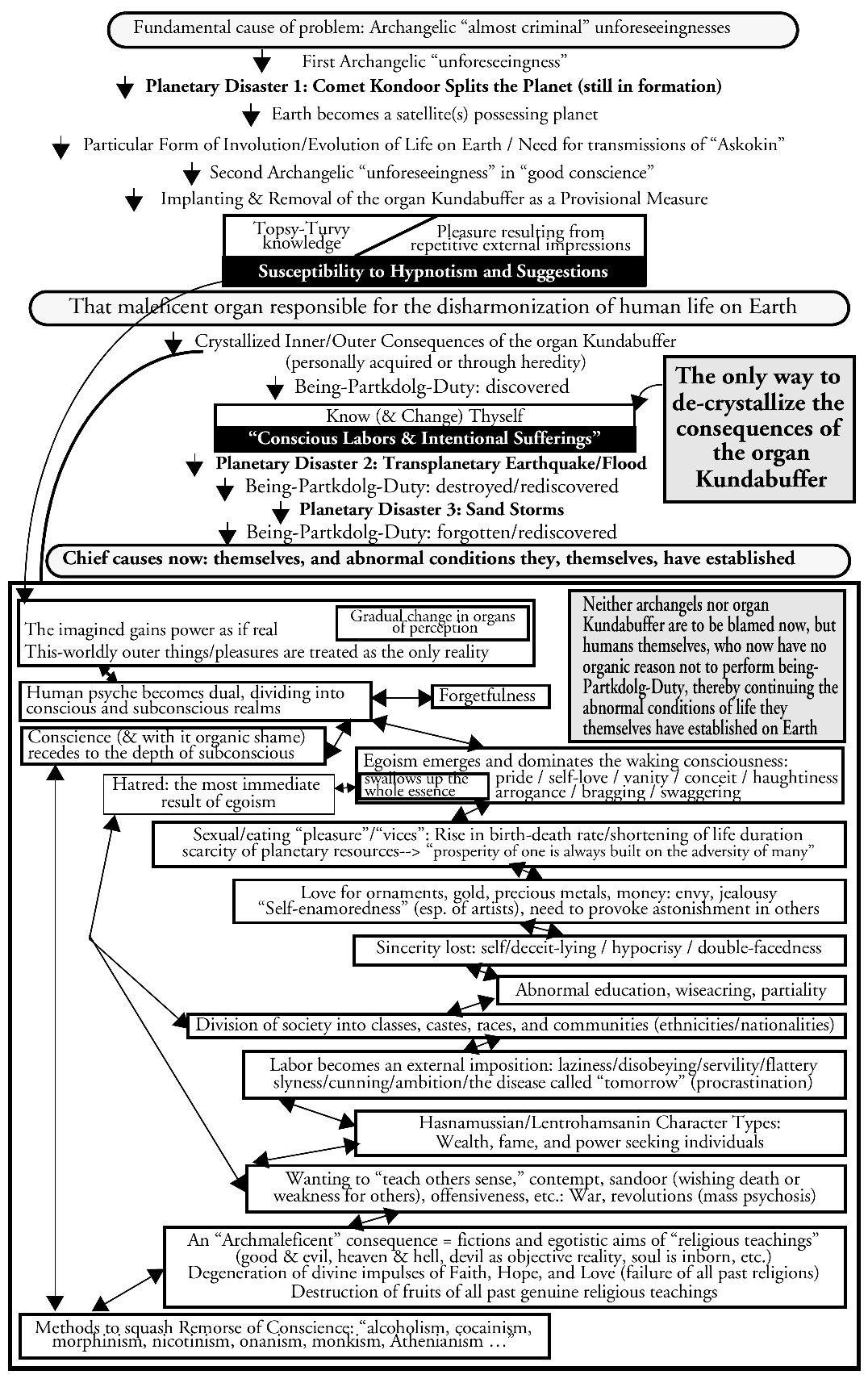

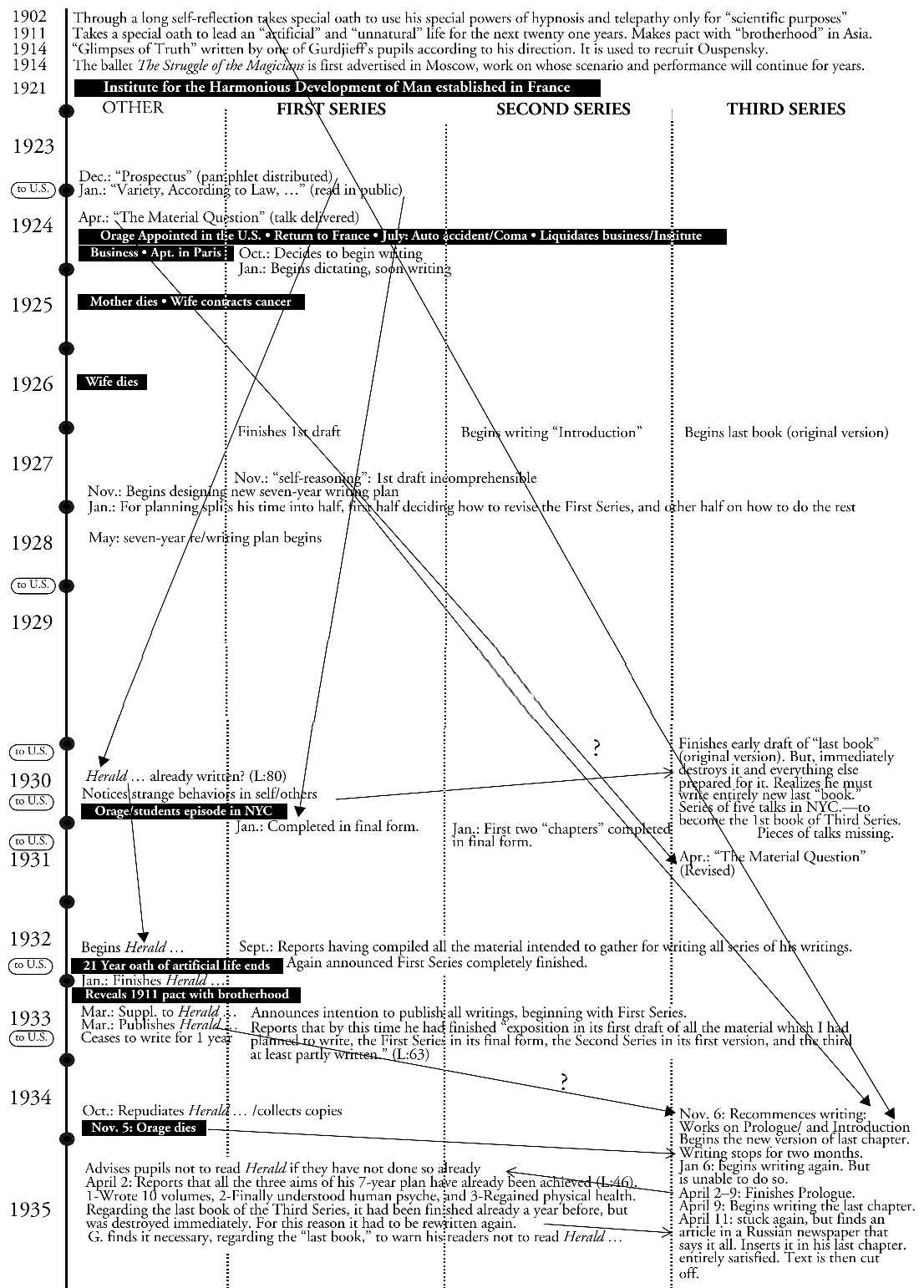

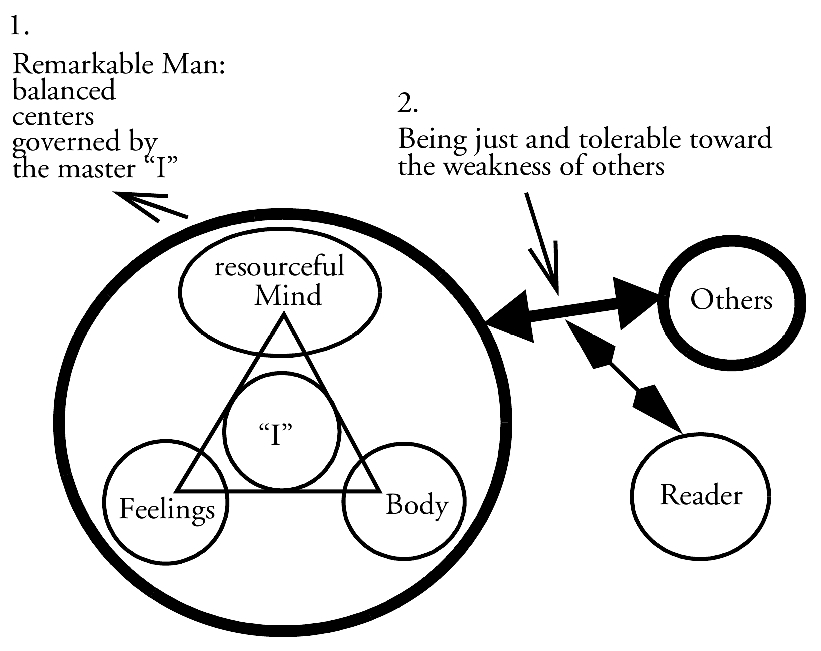

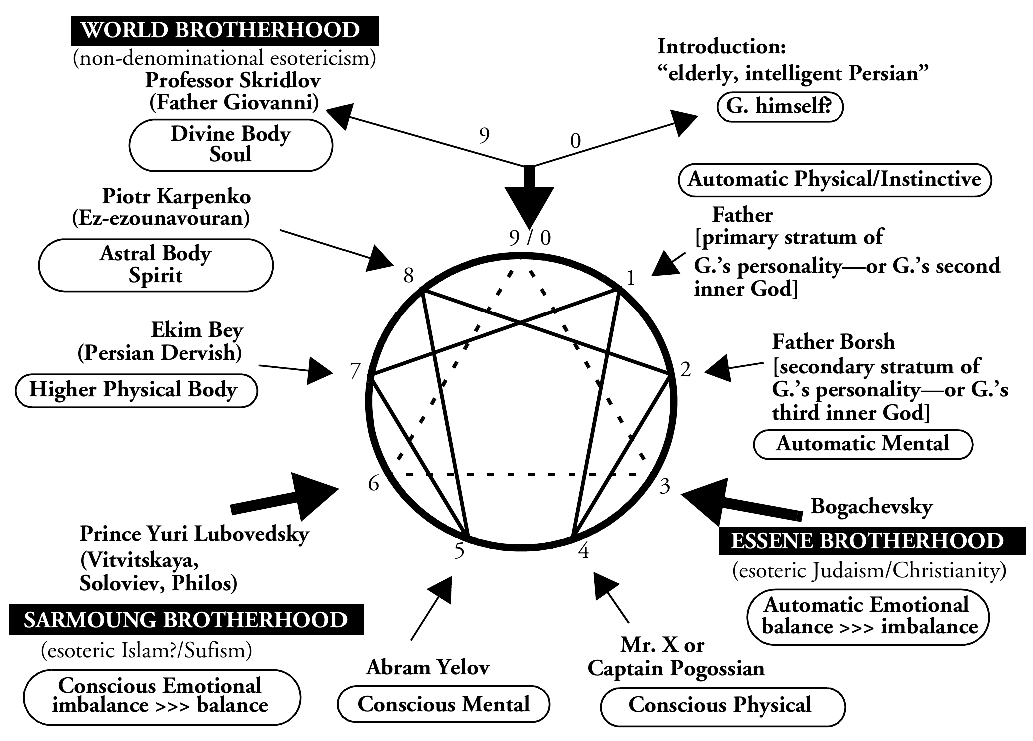

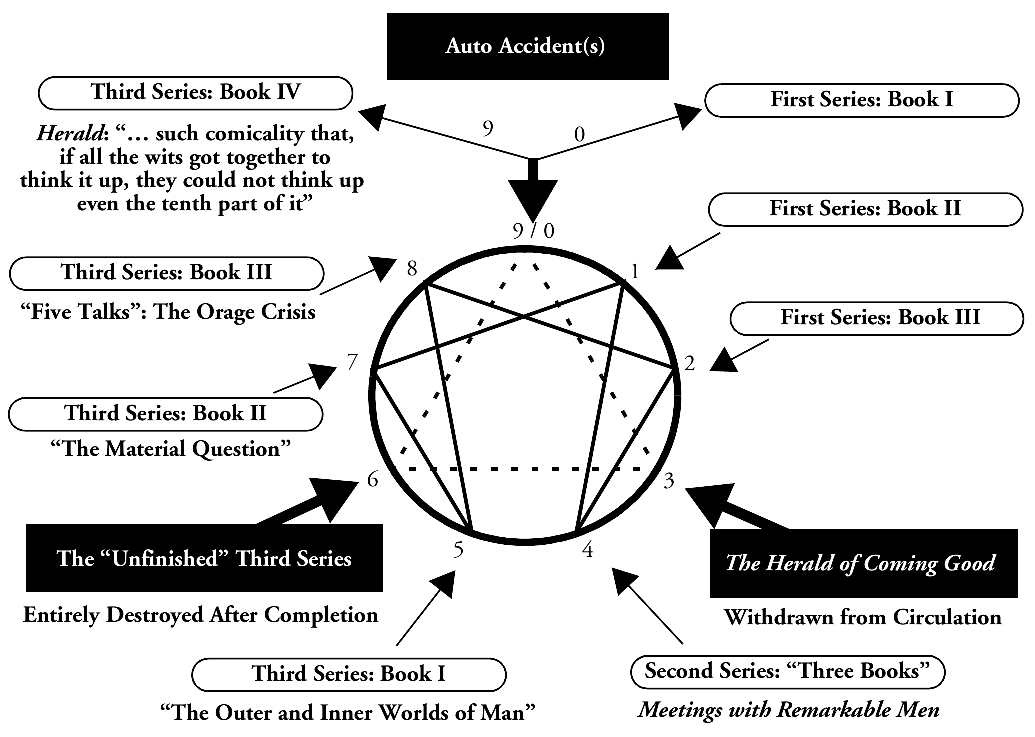

Post-Creation Functioning of the Two Fundamental Laws Pre-Creation Functioning of the Two Fundamental Laws Pre- and Post-Creation Diagrams of the Two Laws Superimposed The Triadic System of Octaves Each Beginning at Successive Shock Points The First Outer Cycle of the Law of Seven as Enacted in the Process of Creation “Centers of Gravity” Crystallizations in a Tetartocosmos The Three Food Circuits in the Human Organism The Common Enneagram of Food, Air, and Impression Assimilation Octaves in the Human Organism Diagrammatic Representation of Gurdjieff’s Conception of the Three Totalities Comprising the Human Organism Gurdjieff’s Conception of the Possibility of Self-Conscious Human Existence as Built into the Fundamental Outer Enneagram of World Creation and Maintenance Gurdjieff’s “Organ Kundabuffer” Theory of Human Disharmonization Chronology of Gurdjieff’s Writing Period Gurdjieff’s Definition of Remarkableness and Its Aspects The Developmental Enneagram of Gurdjieff’s Life as Influenced through Meetings with Remarkable Men as Presented in the Second Series The Enneagram of Crystallization and Decrystallization of the Hypnotic “Psychic Factor” through the Three Series as a Whole |

5 5 5 6 7 7 12 12 16 17 25 37 46 47 69 |

B (or Beelzebub) — Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson: An Impartial Criticism of the Life of Man (All and Everything, First Series)

M (or Meetings) — Meetings with Remarkable Men (All and Everything, Second Series)

L (or Life) — Life Is Real Only Then, When “I Am” (All and Everything, Third Series)

H (or Herald) — The Herald of Coming Good

for my beloved

father Mohammed (Ahad) Tamjidi (1930–2007)

and mother Tayyebeh Tamjidi

This book emerged over the years from a work originally conceived in 1992, culminating as a part of a doctoral dissertation I defended in 2001, deposited in 2002, and subsequently revised extensively. As the deadline for depositing the thesis approached in 2002, I undertook a permissions search and contacted J. Walter Driscoll, an independent scholar from Canada and known since the 1980s for his essays, and editorial and bibliographic contributions to Gurdjieff Studies (Driscoll 1980, 1985, 1997-2004, 2002, 2004, 2007). He responded promptly, providing helpful suggestions and addresses. Subsequently, he read my thesis and invited me to post a lengthy synopsis of it on the 2004 edition of his online bibliography.

Driscoll kindly read a draft of Gurdjieff and Hypnosis when Palgrave solicited him to anonymously review it in early 2008. At his initiation, his editorial suggestions, insightful comments, and identity were made available and known to me by Palgrave with their contract offer. Driscoll then took much time and care to read a third draft and offer further generous rounds of knowledgeable suggestions. I am delighted that he accepted, upon my suggestion, to write a Foreword to this work and contribute a brief bibliography of Gurdjieff’s English language writings (see Bibliography). Notably tolerant when others’ views diverge from his, Driscoll’s knowledge of Gurdjieff’s writings and of the extensive related literature since almost a century ago is remarkable, and his critical feedback always constructive. However, the key findings of this study and its basic conclusions about Gurdjieff’s writings and their relation to hypnosis preceded my acquaintance with Driscoll and I am solely responsible for the views expressed and for any errors and omissions that the study may contain.

I wish to sincerely thank noted scholars Paul Beekman Taylor and Basarab Nicolescu for their careful reading and consideration of this manuscript and for providing helpful suggestions and kind endorsements. I also thank Harold Johnson for his kind understanding, advice, support, and appreciation of this study. Many thanks also go out to Palgrave’s editor Christopher Chappell, his assistant Samantha Hasey, other Palgrave editors Farideh Koohi-Kamali, Brigitte Shull, and Luba Ostashevsky, and Production Associate Kristy Lilas, for their kind support and assistance. Maran Elancheran also contributed helpful proofreading assistance.

This work is dedicated to the memory of my beloved father, Mohammed (Ahad) Tamjidi, who passed away so suddenly in August 2007 in Iran, and to my beloved mother, Tayyebeh Tamjidi, whose presence I still have, to enjoy and cherish. At its roots, this effort is an expression of my ineffable appreciation of the respect for autonomy of spirit and harmonious human development they cultivated in me. I also wish to thank my dear sisters Tahereh and Nahid in Iran, and their children Sahar (and her husband Peyman and their beautiful Noura), Nima, Iman, and Tarlan, and my dearest lifelong friend and spouse Anna Beckwith and her loving family, all of whose company and endless patience also made this work possible.

G. I. Gurdjieff (circa 1870 to 1949) remains as enigmatic as the inscriptionless and inscrutable pair of dolmans which have guarded his family plot in Fontainebleau for sixty years. A polyglot and privately tutored autodidactic from obscure Greek-Armenian parentage in the Russian occupied southern slopes of the Caucasus of the late nineteenth century, he emerged as a self-vaunting and unorthodox yet remarkably able choreographer, composer, hypnotherapist, memoirist, mythologist, novelist, philosopher, and psychologist.

Gurdjieff tells us that by the mid 1890s his expeditionary band called ‘Seekers of Truth’ was engaged in scientific missions and monastic pilgrimages in remote regions of Central Asia, that his practical knowledge of hypnotism was deepening and that he had begun to give himself out “to be a ‘healer’ of all kinds of vices” (H:20). After more than a decade spent honing his discoveries in Europe, Africa, Russia and Central Asia, he adopted—as he characterized it—the “artificial life” of a hypnotist-magus around 1911-1912 (H:11-13, 63, 68). His avowed purpose in the twenty-one year undertaking that followed was to understand “the aim of human life” (H:1), to attract sufficient followers of every human type as subjects for observation and experiment and upon whom he hoped to depend for their services as musicians, dancers, artists and writers to verify and promote his auspicious system (H:22-24).

Gurdjieff brashly stormed the stages of Europe and America between the early 1920s and the mid 1930s, cloaked in his adopted Svengali mystique of “tricks, half-tricks, and real supernatural phenomena” (Nott 1961:15)— including perhaps a sound psycho-spiritual teaching for posterity. The dramatic performances with his dance troupe and brassy orchestra made headlines in Paris, London, New York and Chicago. By the early 1940s Gurdjieff had garnered sufficient financial credit among his Paris admirers to quietly operate a neighborhood soup-kitchen from his “back staircase” (Tchekhovitch 2006:198-99) and survive the Nazi occupation of Paris. Immediately following World War II his American and British flocks gathered in Gurdjieff’s small Paris apartment to endure plate-in-hand standing-room-only dinners and rounds of “Idiot” toasts. Then they sat or squatted in the living room past the wee hours for interminable oral readings of his then unpublished space odyssey Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. These festive pedagogical occasions with Gurdjieff ended at his death on October 29, 1949 (Moore 1991:316).

Gurdjieff should have been forgotten by now, or perhaps recalled only in occasional footnotes such as the following typical gossip about him, recorded in the joint 1920s memoir of Robert McAlmon and Kay Boyle1— two expatriate American writers in Paris when Eliot, Hemingway, Joyce, Mansfield, Pound, Williams, and a host of major English-language authors frequented café tables. Boyle recounts that one afternoon in 1923 at the Café de la Paix, while Gurdjieff sat at an adjacent table, she, McAlmon, and their host Harold Loeb heard an anonymous young American (who had visited a friend at Gurdjieff’s Institute at the Prieuré) say:

[Gurdjieff’s] cult has been spreading among people I thought were more or less sensible … Jane Heap, Margaret Anderson and Georgette Leblanc got involved … (I [Kay Boyle] remembered then that it was there that Katherine Mansfield died.). It’s a mass hypnotism of some kind. Gurdjieff started years back in the East as a hypnotist … In their state of half starvation and overwork, they don’t care to think or feel on their own. They live on their hallucinations.

The sinister, manipulative and exploiting hypnotist Svengali was a character invented by George du Maurier (1834-1896) in his 1894 melodrama, Trilby. A retiring amateur hypnotist and not particularly notable British writer, Du Maurier was overwhelmed by unwelcome public attention when the book created an international sensation and became perhaps the best-selling English-language novel of the nineteenth century. It portrays the sweet hapless Trilby as an innocent, warm-hearted artist’s model who, hypnotically seduced into marriage with the spectral conductor Svengali, becomes his zombie song-bird. Representing the quintessence of mesmeric entrapment and hypnosis run-amuck—then dominant topics of salon debate—the characters of Svengali and Trilby were, by the turn of the century, galvanized into iconic archetypes for Victorian-Edwardian preoccupations with the dark forces of the unconscious, repressed sexuality, and occultist esotericism.2

Trajectories of both Gurdjieff and the stereotype of Svengali dovetailed during the decades between 1890-1910. By the time Gurdjieff had established his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at Fontainebleau in France and sufficiently trained his troupe of talented and disciplined performers (1919-1922), the image of Svengali was a firm fixture in the minds of their European and American audiences. Did Gurdjieff simply exploit the stereotype or fall prey to it? Both? Neither? In any case, Gurdjieff was no ‘one-trick-pony’ to be dismissed by history as simply another sordid Svengali. The timeliness and inherent power of his music, dances, writings, practices and ideas sustained small groups of dedicated disciples who systematically, and often behind the scenes, promoted the study of Gurdjieff. This, despite the fact that many of these followers were irrevocably alienated from ‘the master’ by his ruthlessly compassionate—and sometimes dramatically staged—dismissals and uncompromising demands; is it naïve oversimplification to think these confrontations were simply hard lessons in deprogramming to wean them from his charismatic presence?

1. Robert McAlmon and Kay Boyle, Being Geniuses Together: 1920-1930, revised with supplementary chapters and afterword by Kay Boyle (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1984:85-87).

2. For a thorough account of the trans-Atlantic Svengali phenomena generated by du Maurier’s 1894 Trilby, see Daniel Pick’s Svengali’s Web: The Alien Enchanter in Modern Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000). By an odd quirk of history, in November 1934 the remains of A. R. Orage, then recently retired as Gurdjieff’s foremost English disciple and editor, were interred in the same cemetery as those of George du Murier, at St. John’s-at-Hampstead Churchyard.

I have had the good fortune and privilege to become a welcome spectator and commentator as Dr. Tamdgidi expanded on and transformed the study of Gurdjieff in his 2002 Ph.D. dissertation, “Mysticism and Utopia.” The original, elucidating book that has emerged and which you hold in hand sets a benchmark for Gurdjieff Studies in relation to two recognized but insufficiently explored areas, his writings as a unified field and his exploitation of hypnosis in its broadest sense. Tamdgidi applies a hermeneutic approach to Gurdjieff’s writings, with a particular focus on Gurdjieff’s pervasive exploitation of hypnotic technique which was figurative and literal as well as literary. Tamdgidi’s study is primarily interpretive, literary (without being pedantic), textual and psychological rather than simply historical and biographical, although these last two domains are also significant in his penetrating analysis.

Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation, the avenues by which we arrive at an understanding of or derive meaning from the object of our attention and examination. Traditionally, hermeneutics developed around the study of scripture as each of the major religions emerged; later it was more generally applied to the study of both classical and modern literature. The term is derived from Aristotle’s Peri Hermeneias (On Interpretation) and evokes obvious associations with the Olympian Greek god Hermes, the winged-sandaled, caduceus brandishing messenger of the gods. Hermes sometimes escorts the dead and thus is one of only four gods—the others being Hecate, Hades, and Persephone—who have unhindered right-of-passage in-and-out of the Underworld. At folkloric levels, Hermes is patron of interpreters, translators, travellers, and the boundaries they cross in order to communicate with aliens. On his darker side, Hermes is associated with the watcher-at-night and whatever can go amiss on the travellers’ road, such as cunning thieves-at-the-gate.

Hermeneutic studies vary widely in attributing primacy of meaning to either the author’s or artist’s intent, the subjects covered or media employed, and each reader’s or viewer’s right to interpretation via whatever school of thought they favour—historical, etymological, textual, psychological, symbolic, etc. At its highest levels, hermeneutics involves the search for meaning via numinous interpretation, be it of poetry, scripture, philosophy, literature, music, art, law or architecture. It is both fitting and timely that Tamdgidi draws for inspiration on all his relevant hermeneutic options in search of meaning in Gurdjieff’s ideas and writings. Gurdjieff’s four distinct books are the product of a self-styled message-bearer of the ‘messengers of the gods,’ a twentieth-century spinner of tales about His ENDLESSNESS, Beelzebub, life on Earth, and ‘all and everything’ between these, including a singular cosmology and psychology. Tamdgidi’s compact interpretation of Gurdjieff emphasizes—for the first time—a search for meaning based on recognizable keys within about 1,800 pages of Gurdjieff’s four texts as a single body of work, with particular focus on subliminal and subconscious dimensions of impact and interpretation, an approach that might be termed the ‘Hermeneutics of Gurdjieff.’

During the past sixty years, an enormous and ever-expanding literature has emerged about Gurdjieff, a good deal of it anecdotal, expository or apologetic—and too much of it biased, fictitious and/or ideological. Too little of the literature is independent or (dare one add) intelligently critical. And, despite the amount published about Gurdjieff or expositions of his ideas based on secondary sources, few writers offer significant or systematic analyses of Gurdjieff’s own writings. Thus, Tamdgidi’s work is an important original contribution to the constructive, independent, and critical study of Gurdjieff’s four books. He presents abundant evidence for his arguments via a thorough, thoughtful examination of The Herald of Coming Good (1933), All and Everything: Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (1950), Meetings With Remarkable Men (1963), and Life Is Real Only Then, When “I Am” (1978). Drawing on copious citations from these books, Tamdgidi assembles a chronology of Gurdjieff’s life, simultaneously providing a detailed examination of Gurdjieff’s cosmology, psychology, and an examination of the nine-pointed “enneagram,” a unique symbol Gurdjieff developed to encapsulate the ‘universal laws’ that frame his mytho-cosmology, his epistemology and his psychology.

Anyone who has seriously attempted to read Beelzebub’s Tales or Meetings with Remarkable Men can vouch for their intentionally beguiling or ‘hypnotic’ effect. These readers will appreciate Tamdgidi’s interpretive virtuosity and focus—he keeps each tree and the entire forest in sight throughout. Tamdgidi’s study will prove challenging for those who have not read Gurdjieff but it will also encourage them to seek their own verification and follow Gurdjieff’s seemingly pompous but truly “Friendly Advice” about trying to “fathom the gist” of his writings. His counsel is posted facing the Contents page of Beelzebub’s Tales, and concludes:

Read each of my written expositions thrice … Only then will you be able to count upon forming your own impartial judgement, proper to yourself alone, on my writings. And only then can my hope be actualized that according to your understanding you will obtain the specific benefit for yourself which I anticipate, and which I wish for you with all my being.

J. Walter Driscoll

Vancouver Island on the Pacific

June 29, 2009

I learned that the boy in the middle was a Yezidi, that the circle had been drawn round him and that he could not get out of it until it was rubbed away. The child was indeed trying with all his might to leave this magic circle, but he struggled in vain. I ran up to him and quickly rubbed out part of the circle, and immediately he dashed out and ran away as fast as he could. … This so dumbfounded me that I stood rooted to the spot for a long time as if bewitched, until my usual ability to think returned. Although I had already heard something about these Yezidis, I had never given them any thought; but this astonishing incident, which I had seen with my own eyes, now compelled me to think seriously about them. … The Yezidis are a sect living in Transcaucasia, mainly in the regions near Mount Arafat. They are sometimes called devil-worshippers.

—M:65-66

George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1872?-1949) was an enigmatic Transcaucasian mystic philosopher and teacher who has been widely acknowledged for having introduced to the West during the early twentieth century a new teaching that significantly influenced contemporary spirituality.

Gurdjieff is known—through the famous work of his senior early pupil P. D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching (1949), detailing an absorbing account of his conversations with Gurdjieff—for having introduced a rational interpretation and synthesis of Eastern mysticism more accessible to the Western mind. Paradoxically, however, Gurdjieff made every effort in his own writings to build a seemingly impenetrable and mystifying edifice for it.

Consequently, much of the knowledge about Gurdjieff’s teaching, and even about his life, needs to be untangled and defragmented by deciphering the meanings concealed beneath the symbolic architecture of all his texts. This furnishes the rationale for conducting fresh and independent explorations of his life and teaching by adopting a hermeneutic approach to the study of his writings. The hermeneutic approach encompasses the intentions both to conduct an indepth textual analysis and to interpret the text using its own symbolic and meaning structures.

My aim in this study is to shed new light on Gurdjieff’s life and teaching in general and his lifelong interest in and practice of hypnosis in particular, through a hermeneutic study of all four of his published writings. I especially explore his “objective art”1 of literary hypnotism intended as a major conduit for the transmission of his teachings on the philosophy, theory, and practice of personal self-knowledge and harmonious human development. In the process I explain the nature and function of the mystical shell hiding the rational kernel of his teaching—thus clarifying why his mysticism is “mystical,” and Gurdjieff so “enigmatic,” in the first place. I also argue that, from his own point of view, Gurdjieff’s lifelong preoccupation with hypnosis was not an end in itself or merely aimed at advancing his personal fame and fortune, but mainly served his efforts to develop and spread his teaching in favor of human spiritual awakening and harmonious development.

The study raises and examines various issues related to Gurdjieff’s teaching and life that can also provide substantial material of interest for cross-fertilization of other studies of Gurdjieff as well as those in literature, psychology, hypnotism, mysticism, and religion in general in both academic and non-academic settings. It can be used to further explore the dynamics of mystical schools and teachings, especially in regard to spiritual conditioning, cult behavior, and dynamics of teacher-pupil relations in small group settings. As such, it aims to mark a critical and appreciative note in Gurdjieff Studies and constructively contribute to the enrichment of spiritual work among those independently attracted to Gurdjieff’s teaching and perhaps also those associated with its official institutions.

It is important to note here that this study is not concerned with evaluating the effectiveness of Gurdjieff’s hypnotic techniques and powers per se, but with substantiating the proposition that he indeed was consciously, intentionally, and systematically preoccupied with and practiced hypnotism throughout his life, including, and especially so, during his career as a writer and through his writings. I believe the study of Gurdjieff from this vantage point can shed important light not only on his life and teaching, but also on the hypnotic nature of other religious and literary texts.

1. By “real, objective art” (Ouspensky 1949:27) Gurdjieff means a kind of art whose effect on its target audience is precise, predictable, and reproducible with scientific accuracy; it consciously and intentionally affects not only the intellectual but especially the emotional (feeling) sides of its target audience. This is in contrast to “subjective art” where the art may not produce any of its predicted and intended results and impressions on its target audience. “Ancient” objective art—many examples of which Gurdjieff cites, such as the great Sphinx of Egypt, a strange figure on the foot of the Hindu Kush, etc. (Ibid.)—may also contain “inexactitudes,” in terms of intentional deviations from what were regarded as lawful patterns; deciphering such inexactitudes by later generations could render insights about the messages consciously and intentionally hidden by the ancients for their posterity. Gurdjieff’s clearly explicated aim in affecting not only the mind but also the emotions of his readers (B:4, 24-25), along with his purposeful hiding of various meanings in his writings (M:6, 38), are certainly characteristics that he associates with objective art. But how his “objective art” of literary hypnotism is devised and works are what this study aims to illuminate.

Another limitation of this study has to do with its focus on Gurdjieff’s published writings. Of the four major works of Gurdjieff published to date, only The Herald of Coming Good was published and soon withdrawn (by Gurdjieff ) from circulation in 1933 during his lifetime. The galley proofs of the First Series, Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, were inspected and approved by Gurdjieff before his passing in 1949, but the book was formally published in 1950 after his death and reprinted several times since, with a revision appearing in 1992 and 2006. Given the controversy2 surrounding the unaccountable revisions made to the original 1950 edition of the First Series in the 1992 (and the latter’s 2006 reprint) adaptation, the present study will use the first, 1950, edition of the First Series for its textual analysis. The Second Series (Meetings with Remarkable Men) of Gurdjieff’s writings was published posthumously by Gurdjieff’s pupils in 1960 in French and in 1963 in English while his Third Series (Life Is Real Only Then, When “I Am”) was first published privately in English in 1975 and then publicly in 1978 and reprinted in 1991. The extent to which the published material of all of Gurdjieff’s writings correspond to or diverge from the manuscripts left by Gurdjieff, and whether there are other pieces of unpublished writings by Gurdjieff, are important questions to explore. However, such a task is beyond the scope and purpose of this study, which is limited to the hermeneutic study of Gurdjieff’s published writings.

Other limitations of this study in regard to its focus (besides the page limit set by the publisher for the book) have to do with engagements with the literature on hypnotism in general and with the secondary literature in Gurdjieff Studies in particular.3 The present study is not concerned with how Gurdjieff’s views on and practice of hypnotism compare to those contained in the past or present literature on and practices of hypnosis and hypnotism. I am mainly concerned here with the in-and-of-itself enormous task of hermeneutic deciphering of Gurdjieff’s own interpretation and practice of hypnotism as reflected in and transmitted through his writings. I believe that the integral study of all of Gurdjieff’s own writings with a specific focus on the question of hypnosis not only has substantive merits and been long absent in Gurdjieff Studies, but also is consistent with Gurdjieff’s own explicit injunctions to systematically read his writings as a whole to fathom the gist of his teaching.

Therefore, as much as I would like to explore the correlations of the findings of this study with scientific research and the vast body of literature on hypnotism, these unfortunately remain outside the scope of this book. Among such important literature, one can mention the work of noted American psychiatrist and hypnotherapist, Milton H. Erickson (2006; see also Havens 2005, and Rosen 2005) whose exploitation of indirect suggestions and confusion techniques, storytelling using metaphors, resistance, shocks, and ordeals, clearly parallel Gurdjieff’s. Serious and highly creative and fascinating are also the works of Adam Crabtree (1985, 1993, 1997) whose studies of the history of Mesmerism, hypnosis, and psychological healing also include specific references to Gurdjieff’s ideas on human multiplicity (though not in regard to Gurdjieff’s writings as means for inducing hypnosis). Crabtree’s writings provide an important historical context for understanding the rising interests of spiritual seekers such as Gurdjieff in hypnotism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Europe (including Russia and its environs). Also of note are the writings of prominent transpersonal psychologist Charles Tart on meditation, hypnosis, and “waking up” (1986); Tart’s work has developed in intimate conversation with Gurdjieff’s ideas and teaching amid those of other traditions. The works of Arthur J. Deikman (1982, 1990, 2003) on the “observing self ” and of cult behavior in mystical schools and society at large are also relevant to the implications of the present study, while Robin Waterfield’s Hidden Depths: The Story of Hypnosis (2002) provides a detailed yet accessible and wide historical coverage of its theme while recognizing the relevance of the ideas of Gurdjieff and Tart’s work on the subject.

These important avenues of research will certainly enhance my study, an earlier version of which was originally advanced in 2002. I am also pleased to see the American clinical neuropsychologist and hypnotherapist Joseph A. Sandford has recently (2005) recognized the relationship between Gurdjieff, hypnosis and Erickson’s techniques—see, for instance, Sandford’s “Gnosis Through Hypnosis: The Role of Trance in Personal Transformation” published in the proceedings of The International Humanities Conference: All & Everything 2005 (59-67). Therein, Sandford acknowledges that “In reflecting on these Ericksonian techniques of hypnosis it seems to me that Gurdjieff used hypnosis more than most of us have ever realized. Gurdjieff’s book, All and Everything, uses all of these [Ericksonian] methods …” (59); however, Sandford’s essay is not devoted to the explication of this theme, but to an exploration of Gurdjieff’s thoughts on hypnosis and the hypnotic process as presented in his writings.

2. According to Gurdjieff Studies bibliographer and scholar J. Walter Driscoll (personal communication on March 28, 2009):

In 1992, after four decades of in-house debate, the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York (under their imprint, Triangle Editions, Inc.), issued an adaptation of the First Series, with no indication of its purpose, methods or sources—only the statement, “This revision of the English translation first published in 1950 has been revised by a group of translators under the direction of Jeanne de Salzmann.”

The adapted translation is in late twentieth-century colloquial American English. At approximately 1135 pages (circa 335400 words), it is about 6.5% (circa 23200 words, about 65 pages) shorter than the early twentieth-century British prose original finalized by Gurdjieff and published in 1950 with 1238 pages (circa 358600 words). In places, the revision departs radically from the original English edition; it apparently draws on the Russian manuscript and on Jeanne de Salzmann’s French translation of 1956. In 2006, a “second edition” appeared, containing unspecified “further revisions” and a four-page “Editors’ Note” which avoids well-documented accounts of Gurdjieff’s attentive philological supervision of his English edition, particularly with Olga de Hartmann. Fluent in Russian and English, de Hartmann “was certain that Orage’s translation was very exact. Finally, after many attempts, Mr. Gurdjieff was satisfied” (Hartmann and Hartmann 1992:240-41).

Triangle Editions’ anonymous editorial team dismisses the original 1950 English edition as “awkward … unwieldy … needlessly complex and, for many readers, extremely difficult to read and understand.” They assure readers that Gurdjieff “could not have judged, much less approved the English text” for its 1950 publication, and rush to promote the stylistic and linguistic changes which “Mme de Salzmann … left them to complete.”

3. I must further add here that limitations of space and focus do not also allow me to elaborate in this study on the sociological and social psychological significance of Gurdjieff’s ideas and their relevance to liberatory social theorizing and practice. Some efforts in this regard may be found in my other writings, including: “The Simultaneity of Self and Global Transformations: Bridging with Anzaldúa’s Liberating Vision” (forthcoming); “Utopystics and the Asiatic Modes of Liberation: Gurdjieffian Contributions to the Sociological Imaginations of Inner and Global World-Systems” (2009); “From Uopistics to Utopystics: Integrative Reflections on Potential Contributions of Mysticism to World-Systems Analyses and Praxes of Historical Alternatives” (2008a); Advancing Utopistics: The Three Component Parts and Errors of Marxism (2007a); “Abu Ghraib as a Microcosm: The Strange Face of Empire as a Lived Prison” (2007b); “Anzaldúa’s Sociological Imagination: Comparative Applied Insights into Utopystic and Quantal Sociology” (2006) revised and published as “‘I Change Myself, I Change the World’: Gloria Anzaldúa’s Sociological Imagination in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza” (2008b); “Orientalist and Liberating Discourses of East-West Difference: Revisiting Edward Said and the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam” (2005b); “Freire Meets Gurdjieff and Rumi: Toward the Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Oppressive Selves” (2004a); “Rethinking Sociology: Self, Knowledge, Practice, and Dialectics in Transitions to Quantum Social Science” (2004b); “Mysticism and Utopia: Towards the Sociology of Self-Knowledge and Human Architecture (A Study in Marx, Gurdjieff, and Mannheim)” (2002); and ‘I’ in the World-System: Stories from an Odd Sociology Class (Selected Student Writings, Soc. 280Z: Sociology of Knowledge: Mysticism, Utopia, Science) ([1997] 2005a). Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge (2002-), founded in and published since 2002, has provided an annual forum that was inspired by my appreciative critique of Gurdjieff’s work in my doctoral dissertation.

Systematic studies of all of Gurdjieff’s writings in relation to one another with a specific focus on the place of hypnosis in his work have therefore been basically absent in the secondary literature in Gurdjieff Studies.4 And this is more puzzling given the central significance accorded by Gurdjieff himself to hypnosis. Most writings on Gurdjieff have been by those affiliated with his teaching, going back to the widely published book on Gurdjieff written by P. D. Ouspensky (1949). I have not been a part of any Gurdjieff-affiliated organization, and became interested in Gurdjieff’s life and writings as part of my academic research and personal interest. My personal interest began from ‘repeated’ viewings of the film “Meetings with Remarkable Men”—based on Gurdjieff’s Second Series and directed by Peter Brook in collaboration with Gurdjieff’s senior pupil, the late Jean de Salzmann. This was followed by my ‘repeated’ readings of Gurdjieff’s four books, the volume of his talks as reported by his pupils (Views from the Real World, [1973] 1984), as well as various writings about him, his teaching, and his pupils. I subsequently became increasingly ‘preoccupied’ with his life and ideas, and contemplated ‘joining’ one or another Gurdjieff-affiliated group, each time postponing such efforts until ‘I was ready.’

However, an unusual experience during a ten-day meditation retreat in January 1995 that was unrelated to Gurdjieff groups—though was made possible by my growing interest in mysticism following my exposure to Gurdjieff’s writings—brought to my attention in a practical sense the possibility and the extent of conditioning one may subconsciously endure in organized spiritual practices. Three days into the meditation retreat, I not only experienced a state of mind, concentration, and attention I did not consider possible before, but also realized, using the heightened awareness achieved while drawing on my sociological training, that I was caught amid a highly sophisticated yet quite subtle mode of hypnotic conditioning being delivered, consciously or not, by the organizers of the retreat. This prompted me to try and understand during the rest of the retreat the nature of the ongoing hypnotic process at hand on the one hand, and, on the other, to devise and implement certain efforts and strategies to counter the hypnotic influence at the intellectual as well as emotional and sensual levels while I was still at the retreat. The nature of my experience there requires much more time and space to reflect and report on and could perhaps be the subject of another book; however, for the purpose of this study, it should suffice to note here that the experience awakened me to the possibility and the extent that I may have already been subjected to similar conditioning not only in relation to other cultural, including academic, traditions, but also and especially to Gurdjieff’s teaching itself. It is one thing to “know” that one may be subjected to cultural conditionings of various kinds; it is another to awaken to it in a deeply shocking way.

Paradoxically, while my awareness of such conditionings in life had been heightened by reading Gurdjieff’s books, at the same time I increasingly felt that I may have as well fallen asleep to his own ideas. In other words, I confronted the precarious state of noticing my spiritual confinements not only in life in general, but also in relation to the very teaching that had heightened my awareness to the possibility of such conditioning. In his semi-autobiographical Second Series, Gurdjieff tells of a strange incident in his childhood when he confronted a Yezidi boy, belonging to the so-called “devil-worshipping” religious sect in the region, who could not get out of a circle drawn around him unless it was partly rubbed away by others (see the epigraph to this Prologue). Now, I found myself as if inside a “Yezidi circle” that Gurdjieff, the author of Beelzebub’s Tales, and the alleged inventor of that strange “circular” enneagram, had drawn around me and his readers through his writings, teaching, and spiritual symbol. Yet, I was also reminded of another of Gurdjieff’s aphorisms—that to escape, one must first realize that one is in prison. Gurdjieff had drawn a circle, but had also rubbed away a part of it so that “the boy” could escape. Why?

My decision at that time to incorporate into my doctoral research the study of Gurdjieff along with those of Karl Marx and Karl Mannheim (respectively representing mystical, utopian, and academic traditions that had also variously shaped my thinking and life) was thus significantly fueled by a need for understanding the nature and causes of my own ‘attraction’ to Gurdjieff’s ‘enigmatic’ life and teaching. In light of, and in many ways due to, these threefold personal, social, and academic interests, I soon realized that maintenance of organizational distance from Gurdjieff-affiliated groups was substantively and methodologically significant during the conduct of the study. I will further elaborate on this issue in the Introduction.

Most studies of Gurdjieff, often carried out by those at one time or another associated with organizations following Gurdjieff’s teaching, take for granted his coded words regarding his decision not to pursue his hypnotic powers following a vow he made to himself to that effect at a certain point in his life. The present study, based on a detailed analysis of Gurdjieff’s own writings, challenges such (mis)interpretations of Gurdjieff’s words. Rather, I argue that an appreciation of Gurdjieff’s life and teaching can best be possible in consideration of (1) the extent to which he regarded the human condition of living in sleep, as a machine or a prisoner, to be a by-product of human suggestibility and propensity to habituation and hypnosis arising from the disharmonious and separate workings of the physical, intellectual, and emotional centers of the human organism, and (2) the extent to which he consciously, intentionally, and systematically continued to pursue his career as a “professional hypnotist” through his writings. Gurdjieff’s lifelong interest in and practice of hypnosis are thereby not marginal but at the heart of his teaching, and worthy of substantial and substantive studies of which the present work is a first systematic beginning.

There is a continuing tension in this study between an effort in trying to understand a text based on Gurdjieff’s indigenous meanings and an implicit and unexpressed (though real) effort on my part in not letting judgments in secondary literature on Gurdjieff interfere with a hermeneutic understanding of his work and life. I think in this sense Gurdjieff’s writings are different from many “ultra esoteric” texts whose meanings remain forever hidden. According to the sociologist Ralph Slotten’s “Exoteric and Esoteric Modes of Apprehension” (1977), there is not a dualism but a spectrum lying in-between esoteric-exoteric textual elements in spiritual writings. He terms such mid-range variants of hermeneutic writing as “eso-exoteric” or “exo-esoteric” in style, and in fact identifies even further, sevenfold, gradations of exotericity and esotericity in spiritual texts (202). In Gurdjieff’s case, similarly, while he hides important elements of his thought in one fragment, he also offers the hidden message—often quite explicitly, candidly, even shockingly to his reader’s face, in a straightforward and at times humor-laden way—in another fragment of his writings. So, there is good reason to rely on Gurdjieff’s own writings and the “hermeneutic circle” of moving back and forth between the puzzling meanings of his part and whole literary symbols in order to decipher the gist of his writings. What one does with the gist discovered, however, is a different matter; certainly, one has to always maintain distance to avoid becoming trapped in the Yezidi circle of Gurdjieff’s hypnotic hermeneutics, woven in the guise of his father’s “kastousilian” (M:38) style of conversation and storytelling.

The dialectical mode of hermeneutic analysis focusing on the inner landscape and contradictions of a weltanschauung is in my view reasonably effective and helpful in yielding an empathetic understanding of a thinker’s mind (cf. Tamdgidi 2007a). Similarly, I should note that my purpose in studying Gurdjieff’s text (and biography through his text) here is to engage with Gurdjieff’s life and teaching in his own terms, and limit the exploration to the subject of the place of hypnosis in his “scientific” and literary pursuits, rather than to delve into his personal virtues or vices—which, provided one was interested in doing so, would require much more substantial uses of secondary biographical and historical sources.

I see Gurdjieff as a multitude of selves, some Svengali-type, black magician and “devilish” perhaps, others “Ashiata Shiemashian” (as how he idealized his white magician selves), and yet others of all hues and degrees of virtuosity in between. I see all characters in Gurdjieff’s literary dramaturgy as representing one way or another his own selves in a world-historical, contemporary, and utopystic dialogue with one another—his writings being, ultimately, a vast cosmological and psychological effort on his part to understand and perhaps heal his low and high selves self-confessedly caught in the Purgatory of much remorse of conscience; yet, he was hopeful in finding a way to help liberate his soul and those of his fellow “three-brained beings.” It is therefore difficult (and in fact counter-Gurdjieffian) to consider whether Gurdjieff was wholly this or that, since, as his writings reveal, he himself seemed to be also much like—or perhaps unlike, that is, even more sharply polarized and self-conscious than—us all, a legion of I’s.

According to C. Wright Mills, the sociological imagination “enables its possessor to understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals” (1959:5). Gurdjieff’s writings as a whole—especially the dialogical style and structure of all his writings in their various forms where significant public issues and meanings are intricately interwoven, as in a delicate Persian carpet, into the fabric of everyday personal conversations within and across all the “three brains” of his invented personages—present an ingenious and creative way of exploring and advancing the sociological imagination in comparative and transdisciplinary trajectories.

Gurdjieff was an ashokh. His text is not confined to the printed word, nor even to the oral tradition he left behind, but is also written in the physical movements, mental exercises, emotional dances, and the music of a legacy that radically challenges the narrow and dualistic Western notions of the self and society, and thereby sociology. His mystical tales—linking the most intimate personal troubles with ever larger, world-historical, and even cosmically-conscious, public issues concerning humanity as a whole—are highly innovative and colorful exercises in alternative Eastern sociological imaginations meeting their ultimate micro and macro horizons.

4. My basic thesis on and detailed exposition of the place of hypnosis in Gurdjieff’s life and teaching was defended in 2001 and deposited with UMI as part of my doctoral dissertation in 2002. In her Gurdjieff: The Key Concepts (2003) Sophia Wellbeloved acknowledged that Gurdjieff’s teaching as a whole may be considered as an “alternative form of hypnotism” and that for Gurdjieff “hypnotism was both the cause and the cure” (101). She also briefly recognized that Gurdjieff’s use of “kindness, threats and hypnotism” as means for influencing his pupils was also echoed in Gurdjieff’s text itself, “having encouraging, threatening, and spellbinding stories” (106). For anyone acquainted with all of Gurdjieff’s writings it can be self-evident that Gurdjieff himself acknowledged having been deeply interested in hypnosis and hypnotism; that he was a “professional hypnotist” for some years; that he “scientifically” and “experimentally” practiced it for a while on his pupils; that he continued to practice it for the purpose of healing addiction or other ailments throughout his life; that he regarded hypnosis as both a cause and a means of healing human spiritual sleep and mechanicalness; or even that his writings contain much information about the above varieties of interests in and practices of hypnotism. What remains marginal, or absent—as evident, for instance, in Wellbeloved’s excerpt on Gurdjieff’s “Writings” (2003:226-228)—is a consideration for the proposition that Gurdjieff’s writings themselves were conscious, intentional, and systematic efforts in literary hypnotism on the part of Gurdjieff, a thesis central to the present study and advanced in its earlier 2002 version. Wellbeloved’s study, Gurdjieff, Astrology & Beelzebub’s Tales (2002), based on her earlier doctoral dissertation and mainly focused on Gurdjieff’s First Series (as evident in the book’s title and noted elsewhere, e.g., p. 234), was devoted to discovering an astrological logic to Gurdjieff’s First Series and did not advance a thesis in specific regard to Gurdjieff’s writings as hypnotic devices.

… to understand clearly the precise significance, in general, of the life process on earth of all the outward forms of breathing creatures and, in particular, of the aim of human life in the light of this interpretation.

—H:13

As a result of pursuing this method for three days, while I did not arrive at any definite conclusions, I still became clearly and absolutely convinced that the answers for which I was looking, and which in their totality might throw light on this cardinal question of mine, can only be found, if they are at all accessible to man, in the sphere of “man’s-subconscious-mentation.”

—H:18-19

I began to collect all kinds of written literature and oral information, still surviving among certain Asiatic peoples, about that branch of science, which was highly developed in ancient times and called “Mehkeness”, a name signifying the “taking-away-of-responsibility”, and of which contemporary civilisation knows but an insignificant portion under the name of “hypnotism”, while all the literature extant upon the subject was already as familiar to me as my own five fingers.

—H:19

Mysticism has traditionally been concerned with seeking human spiritual awakening from the hypnotic sleep of every day life in favor of attaining direct knowledge and/or experience of the hidden meaning, reality, and truth of all existence (cf. Underhill [1911] 1999; Tart 1986, 1994; Bishop 1995).

George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1872?-1949), of Greek-Armenian parentage, was an enigmatic Transcaucasian mystic philosopher and teacher whose life and ideas significantly influenced the rise of new religious thought and movements in the twentieth century. According to Jacob Needleman (1996; see also 1993 and 2008) “Gurdjieff gave shape to some of the key elements and directions found in contemporary spirituality” (xi), while Martin Seymour-Smith included Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson among the “100 Most Influential Books Ever Written” (1998:447-452). Charles Tart, a pioneer of transpersonal psychology and prominent scholar of meditation and mysticism, has called Gurdjieff “a genius at putting Eastern spiritual ideas and practices into useful forms” (1986:323), while the renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright (2004) thought of Gurdjieff as one who “seems to have the stuff in him of which our genuine prophets have been made.”1

To contrast his own teaching from other mystical paths in pursuit of human spiritual awakening and development, Gurdjieff reportedly distinguished three traditional mystical ways of the fakir, the monk, and the yogi from one another (Ouspensky 1949:44), depending on whether the physical, the emotional, or the intellectual center of the human organism is respectively exercised as a launching ground to attain ultimate, all-round spiritual development of “man’s hidden possibilities” (47). He argued that these three one-sided ways toward self-perfection are more prone to failure since the required trainings in each take longer (thus are often unrealizable during a single lifetime) and their adepts become often vulnerable to habituating forces upon reentry into social life. In contrast, Gurdjieff reportedly advocated an alternative “fourth way” approach characterized by the parallel development of the physical, emotional, and intellectual centers of the organism not in retreat from, but amid, everyday life.

1. According to psychotherapist and author Kathleen Riordan Speeth, the list of those who have been influenced by Gurdjieff’s life and ideas includes author and poet Rudyard Kipling, Black Renaissance poet Jean Toomer, architect Frank Lloyd Wright, author Margaret Anderson, author Katherine Mansfield, photographer Minor White, painter Georgia O’Keeffe, author Zona Gale, editor Gorham Munson, physicist and physiologist Moshe Feldenkreis, filmmaker Alexandro Jodorowsky, author J. N. Priestley, and director Peter Brook (Speeth 1989:117). At the end of her list Speeth adds “and a surprising number of other public figures who wish to remain nameless” (Ibid.).

In the three series of his published writings, Gurdjieff postponed his autobiographical account until the Second Series because it served him to illustrate the philosophical material presented in the First Series. For this reason, in the present study, and in the brief outline of Gurdjieff’s life and teaching that follows, Gurdjieff’s autobiography will be treated as a part of his teaching narrative rather than standing over and beyond it as contextual and “factual” material. Following the outline, I will present in this Introduction the justifications for and issues raised by adopting a hermeneutic approach to the study of Gurdjieff’s writings.

As is evident in the epigraph to this Introduction, for Gurdjieff answering the “cardinal question” of the sense and purpose of organic and human life (and death) on Earth was closely interlinked with the exploration of human subconsciousness on the one hand, and the (ancient) science and practice of hypnotism on the other. The whole “system” of ideas and practices that Gurdjieff formulated and spread by means of his teaching, in other words, can be considered as an effort to highlight and address the interlinkages of the above three dimensions of his search.

The basic ideas of Gurdjieff’s teaching may thus be stated as follows:

- Human life as the potentially evolving part of organic life on Earth is a mechanically (automatically) operating cosmic apparatus that provides a fertile ground for the possibility of conscious and intentional evolution of at least some human individuals toward immortal union with God;

- Human “subconscious-mentation”—made possible by the “three-brained” fragmentation of the human “individual” organism into separate and independently functioning physical, emotional, and intellectual centers underlying a multiplicity of selves manifested as diverse personalities—is the mechanism that allows human beings to remain in a perpetual state of hypnotic sleep, enslaved to and imprisoned in life, in order to serve the needs of the cosmic apparatus of which they are a part;

- Through teacher-guided and multi-faceted, harmonizing work on oneself amid everyday life aimed at blending one’s fragmented centers, consciousnesses, and personalities into a whole subordinated to a singular, essential master “I” (with “real conscience”), one can awaken to the reality of the meaning of one’s and others’ purposes of life and inevitable physical death, die to the “egoism” that lies at the root of one’s hypnotic attachments to the Earthly life, and thus escape from the cycles of mechanical life and death toward “imperishable” union with God.

Gurdjieff expresses in his writing this “gist” of his teaching as follows:

Such is the ordinary average man—an unconscious slave of the whole entire service to all-universal purposes, which are alien to his own personal individuality.

He may live through all his years as he is, and as such be destroyed for ever.

But at the same time Great Nature has given him the possibility of being not merely a blind tool of the whole of the entire service to these all-universal objective purposes but, while serving Her and actualizing what is foreordained for him—which is the lot of every breathing creature—of working at the same time also for himself, for his own egotistic individuality.

This possibility was given also for service to the common purpose, owing to the fact that, for the equilibrium of these objective laws, such relatively liberated people are necessary.

Although the said liberation is possible, nevertheless whether any particular man has the chance to attain it—this is difficult to say.

There are a mass of reasons which may not permit it; and moreover which in most cases depend neither upon us personally nor upon great laws, but only upon the various accidental conditions of our arising and formation, of which the chief are heredity and the conditions under which the process of our “preparatory age” flows. It is just these uncontrollable conditions which may not permit this liberation.

The chief difficulty in the way of liberation from whole entire slavery consists in this, that it is necessary, with an intention issuing from one’s own initiative and persistence, and sustained by one’s own efforts, that is to say, not by another’s will but by one’s own, to obtain the eradication from one’s presence both of the already fixed consequences of certain properties of that something in our forefathers called the organ Kundabuffer, as well as of the predisposition to those consequences which might again arise …

Great Nature, in Her foresight and for many important reasons … was constrained to place within the common presences of our remote ancestors just such an organ, thank to the engendering properties of which they might be protected from the possibility of seeing and feeling anything as it proceeds in reality. (B:1219-20)

Suggesting that the said “organ” was removed by Nature, but its consequences has continued across generations to the present as a result of human propensity for habituation, Gurdjieff continues to add that the fundamental “reality” which this organ or its consequences help veil from human awareness is the inevitability of one’s own death. He continues:

… suppose they should cognize the inevitability of their speedy death, then from only an experiencing in thought alone would they hang themselves …

Thanks to these consequences, not only does the cognition of these terrors not arise in the psyche of these people, but also for the purpose of self-quieting they even invent all kinds of fantastic explanations plausible to their naïve logic for what they really sense and also for what they do not sense at all …

How is it possible to reconcile the fact that a man is terrified at a small timid mouse, the most frightened of all creatures, and of thousands of other similar trifles which might never even occur, and yet experience no terror before the inevitability of his own death? …

If the average contemporary man were given the possibility to sense or to remember, if only in his thought, that at a definite known date, for instance, tomorrow, a week, or a month, or even a year or two hence, he would die and die for certain, what would then remain, one asks, of all that had until then filled up and constituted his life?

Everything would lose its sense and significance for him …

In short, to look his own death, as is said, “in the face” the average man cannot and must not—he would then, so to say, “get out of his depth” and before him, in clearcut form, the question would arise: “Why then should we live and toil and suffer?”

Whereupon it follows that life in general is given to people not for themselves, but that this life is necessary for the said Higher Cosmic Purposes, in consequences of which Great Nature watches over this life so that it may flow in a more or less tolerable form, and takes care that it should not prematurely cease.

Precisely that such a question may not arise, Great Nature, having become convinced that in the common presences of most people there have already ceased to be any factors for meritorious manifestations proper to three-centered beings, had providentially wisely protected them by allowing the arising in them of various consequences of those nonmeritorious properties unbecoming to three-centered beings which, in the absence of a proper actualization, conduce to their not perceiving or sensing reality …

Do not we, people, ourselves also feed, watch over, look after, and make the lives of our sheep and pigs as comfortable as possible?

Do we do all this because we value their lives for the sake of their lives?

No! We do all this in order to slaughter them one fine day and to obtain the meat we require, with as much fat as possible.

In the same way Nature takes all measures to ensure that we shall live without seeing the terror, and that we should not hang ourselves, but live long; and then, when we are required, She slaughters us …

There is in our life a certain very great purpose and we must all serve this Great Common Purpose—in this lies the whole sense and predestination of our life. (B:1222-27)

The key to the link between the question of the purpose of life and death on the one hand, and the problem of the subconscious mind on the other, is the notion of the “organ Kundabuffer” introduced by Gurdjieff into the texture of his teaching. This “buffer” is one that obstructs the blending of the physical unconscious (instinctive), the emotional subconscious, and the mental consciousness in the individual, impeding him from proper understanding and control over her or his own organism. This buffer acts to prevent the premature realization of the “terror of the situation” of one’s purpose in organic life. It is this buffer that lies at the bottom of the hypnotic sleep of our everyday lives, brought on by nature so as to prevent the human organism’s awakening to the realization of the inevitability of her or his death. However, it is also the transcendence of this buffer and its consequences—which fragment the inner life of the “individual” into separately functioning three centers2—that is at the heart of the purpose of Gurdjieff’s teaching and explains why he was so interested in acquiring the necessary knowledge and skills for the practice of hypnotism.

2. I distinguish between the “unconscious” and the “subconscious,” using them for the physical and emotional centers respectively. Gurdjieff himself also generally associates the “unconscious” with the planetary body throughout his writings. See for instance the passage in the First Series (B:1171) where Gurdjieff advises his grandson to be aware of the “unconscious part of a being,” and to “be just towards this dependent and unconscious part and not require of it more than it is able to give.”

Properly speaking, though, each center has its own unconscious, subconscious, and conscious aspects. Gurdjieff’s exercises were often designed so as to help the pupil see not only the three centers as a whole, but how the whole was also represented in minuscule as aspects of each part. Thus we have the physical, emotional, and intellectual aspects of the physical center, the same of the emotional center, and the same of the intellectual center. Likewise, the association of the three unconscious (instinctive), subconscious, and conscious centers must also be seen as being present within each center as well.

The passages quoted above are from the closing pages of Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson, the first of Gurdjieff’s three series commonly titled All and Everything, all of which follow an oft-repeated presentation of the problem of the threefold fragmentation of human “individual’s” life and consciousness (B:1189-1219). There, via the analogy of carriage, horse, coachman and passenger representing the human being’s physical, emotional, and mental centers and real “I” respectively, Gurdjieff states:

A man as a whole with all his separately concentrated and functioning localizations, that is to say, his formed and independently educated “personalities,” is almost exactly comparable to that organization for conveying a passenger, which consists of a carriage, a horse, and a coachman.

It must first of all be remarked that the difference between a real man and a pseudoman, that is between one who has his own “I” and one who has not, is indicated in the analogy we have taken by the passenger sitting in the carriage. In the first case, that of the real man, the passenger is the owner of the carriage; and in the second case, he is simply the first chance passer-by who, like the fare in a “hackney carriage,” is continuously being changed.

The body of a man with all its motor reflex manifestations corresponds simply to the carriage itself; all the functionings and manifestations of feeling of a man correspond to the horse harnessed to the carriage and drawing it; the coachman sitting on the box and directing the horse corresponds to that in a man which people call consciousness or mentation; and finally, the passenger seated in the carriage and commanding the coachman is that which is called “I.”

The fundamental evil among contemporary people is chiefly that, owing to the rooted and widespread abnormal methods of education of the rising generation, this fourth personality which should be present in everybody on reaching responsible age is entirely missing in them; and almost all of them consist only of the three enumerated parts, which parts, moreover, are formed arbitrarily of themselves and anyhow. In other words, almost every contemporary man of responsible age consists of nothing more nor less than simply a “hackney carriage,” and one moreover, composed as follows: a broken-down carriage “which has long ago seen its day,” a crock of a horse, and, on the box, a tatterdemalion, half-sleepy, half-drunken coachman whose time designated by Mother Nature for self-perfection passes while he waits on a corner, fantastically daydreaming, for any old chance passenger. The first passenger who happens along hires him and dismisses him just as he pleases, and not only him but also all the parts subordinate to him. (B:1192-93)

And it is to this theme that Gurdjieff returns after his discussion of the purpose of human life and the functions of the “organ Kundabuffer,” as he continues to elaborate how by becoming aware and intentionally working on harmonizing and blending the functionings of one’s three centers in order to develop one’s own real “I,” the human individual can choose the path of the river that flows to the ocean of immortality rather than the branch that succumbs to the netherlands of nothingness below:

Although the real man who has already acquired his own “I” and also the man in quotation marks who has not, are equally slaves of the said “Greatness,” yet the difference between them, as I have already said, consists in this, that since the attitude of the former to his slavery is conscious, he acquires the possibility, simultaneously with serving the all-universal Actualizing, of applying a part of his manifestations according to the providence of Great Nature for the purpose of acquiring for himself “imperishable Being”; whereas the latter, not cognizing his slavery, serves during the flow of the entire process of his existence exclusively only as a thing, which when no longer needed, disappears forever. (B:1227)

Gurdjieff insists that knowledge of the human subconscious mind and techniques of hypnotic healing to eradicate the consequences of the so-called “organ Kundabuffer” were “absolute” requirements for transcending the enslaving mechanism of life and death in order to achieve immortality by means of acquiring one’s own “I” and imperishable Soul. When referring to the legacy of Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), for instance, Gurdjieff writes elsewhere in the First Series through the words of “Beelzebub”:

“And in doing this, they criticize exactly that humble and honest learned being of their planet, who, if he had not been pecked to death would have revived that science, which alone is absolutely necessary to them and by means of which alone, perhaps, they might be saved from the consequences of the properties of the organ Kundabuffer.” (B:562)

Gurdjieff’s First Series ends in fact with the following declaration by the elderly Beelzebub to his grandson, Hassein, on his spaceship Karnak: